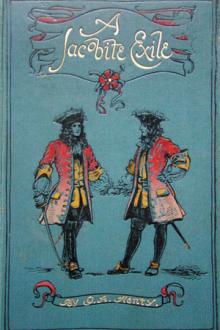

A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕». Author G. A. Henty

"I am pleased with you, men. Your appearance does credit to yourselves and your officers. Scottish troops did grand service under my grandfather, Gustavus Adolphus, and I would that I had twenty battalions of such soldiers with me. I am going hunting tomorrow, and I asked Colonel Schlippenbach for half a company of men who could stand cold and fatigue. He told me that I could not do better than take them from among this company, and I see that he could not have made a better choice. But I will not separate you, and will therefore take you all. You will march in an hour, and I will see that there is a good supper ready for you, at the end of your journey."

Colonel Schlippenbach gave Captain Jervoise directions as to the road they were to follow, and the village, at the edge of the forest, where they were to halt for the night. He then walked away with the king. Highly pleased with the praise Charles had given them, the company fell out.

"Get your dinners as soon as you can, men," Captain Jervoise said. "The king gave us an hour. We must be in readiness to march by that time."

On arriving at the village, which consisted of a few small houses only, they found two waggons awaiting them, one with tents and the other with a plentiful supply of provisions, and a barrel of wine. The tents were erected, and then the men went into the forest, and soon returned with large quantities of wood, and great fires were speedily lighted. Meat was cut up and roasted over them, and, regarding the expedition as a holiday, the men sat down to their supper in high spirits.

After it was eaten there were songs round the fires, and, at nine o'clock, all turned into their tents, as it was known that the king would arrive at daylight. Sentries were posted, for there was never any saying when marauding parties of Russians, who were constantly on the move, might come along.

Half an hour before daybreak, the men were aroused. Tents were struck and packed in the waggon, and the men then fell in, and remained until the king, with three or four of his officers and fifty cavalry, rode up. Fresh wood had been thrown on the fires, and some of the men told off as cooks.

"That looks cheerful for hungry men," the king said, as he leaped from his horse.

"I did not know whether your majesty would wish to breakfast at once," Captain Jervoise said; "but I thought it well to be prepared."

"We will breakfast by all means. We are all sharp set already. Have your own men had food yet?"

"No, sir. I thought perhaps they would carry it with them."

"No, no. Let them all have a hearty meal before they move, then they can hold on as long as may be necessary."

The company fell out again, and, in a quarter of an hour, they and the troopers breakfasted. A joint of meat was placed, for the use of the king and the officers who had come with him, and Captain Jervoise and those with him prepared to take their meal a short distance away, but Charles said:

"Bring that joint here, Captain Jervoise, and we will all take breakfast together. We are all hunters and comrades."

In a short time, they were all seated round a fire, with their meat on wooden platters on their knees, and with mugs of wine beside them; Captain Jervoise, by the king's orders, taking his seat beside him. During the meal, he asked him many questions as to his reasons for leaving England, and taking service with him.

"So you have meddled in politics, eh?" the king laughed, when he heard a brief account of Captain Jervoise's reason for leaving home. "Your quarrels, in England and Scotland, have added many a thousand good soldiers to the armies of France and Sweden, and, I may say, of every country in Europe. I believe there are some of your compatriots, or at any rate Scotchmen, in the czar's camp. I suppose that, at William's death, these troubles will cease."

"I do not know, sir. Anne was James' favourite daughter, and it may be she will resign in favour of her brother, the lawful king. If she does so, there is an end of trouble; but, should she mount the throne, she would be a usurper, as Mary was up to her death in '94. As Anne has been on good terms with William, since her sister's death, I fear she will act as unnatural a part as Mary did, and, in that case, assuredly we shall not recognize her as our queen."

"You have heard the news, I suppose, of the action of the parliament last month?"

"No, sir, we have heard nothing for some weeks of what is doing in England."

"They have been making an Act of Settlement of the succession. Anne is to succeed William, and, as she has no children by George of Denmark, the succession is to pass from her to the Elector of Hanover, in right of his wife Sophia, as the rest of the children of the Elector of the Palatinate have abjured Protestantism, and are therefore excluded. How will that meet the views of the English and Scotch Jacobites?"

"It is some distance to look forward to, sire. If Anne comes to the throne at William's death, it will, I think, postpone our hopes, for Anne is a Stuart, and is a favourite with the nation, in spite of her undutiful conduct to her father. Still, it will be felt that for Stuart to fight against Stuart, brother against sister, would be contrary to nature. Foreigners are always unpopular, and, as against William, every Jacobite is ready to take up arms. But I think that nothing will be done during Anne's reign. The Elector of Hanover would be as unpopular, among Englishmen in general, as is William of Orange, and, should he come to the throne, there will assuredly ere long be a rising to bring back the Stuarts."

Charles shook his head.

"I don't want to ruffle your spirit of loyalty to the Stuarts, Captain Jervoise, but they have showed themselves weak monarchs for a great country. They want fibre. William of Orange may be, as you call him, a foreigner and a usurper, but England has greater weight in the councils of Europe, in his hands, than it has had since the death of Elizabeth."

This was rather a sore point with Captain Jervoise, who, thorough Jacobite as he was, had smarted under the subservience of England to France during the reigns of the two previous monarchs.

"You Englishmen and Scotchmen are fighting people," the king went on, "and should have a military monarch. I do not mean a king like myself, who likes to fight in the front ranks of his soldiers; but one like William, who has certainly lofty aims, and is a statesman, and can join in European combinations."

"William thinks and plans more for Holland than for England, sire. He would join a league against France and Spain, not so much for the benefit of England, which has not much to fear from these powers, but of Holland, whose existence now, as of old is threatened by them."

"England's interest is similar to that of Holland," the king said. "I began this war, nominally, in the interest of the Duke of Holstein, but really because it was Sweden's interest that Denmark should not become too powerful.

"But we must not waste time in talking politics. I see the men have finished their breakfast, and we are here to hunt. I shall keep twenty horse with me; the rest will enter the forest with you. I have arranged for the peasants here to guide you. You will march two miles along by the edge of the forest, and then enter it and make a wide semicircle, leaving men as you go, until you come down to the edge of the forest again, a mile to our left.

"As soon as you do so, you will sound a trumpet, and the men will then move forward, shouting so as to drive the game before them. As the peasants tell me there are many wolves and bears in the forest, I hope that you will inclose some of them in your cordon, which will be about five miles from end to end. With the horse you will have a hundred and thirty men, so that there will be a man every sixty or seventy yards. That is too wide a space at first, but, as you close in, the distances will rapidly lessen, and they must make up, by noise, for the scantiness of their numbers. If they find the animals are trying to break through, they can discharge their pieces; but do not let them do so otherwise, as it would frighten the animals too soon, and send them flying out all along the open side of the semicircle."

It was more than two hours before the whole of the beaters were in position. Just before they had started, the king had requested Captain Jervoise to remain with him and the officers who had accompanied him, five in number. They had been posted, a hundred yards apart, at the edge of the forest. Charlie was the first officer left behind as the troop moved through the forest, and it seemed to him an endless time before he heard a faint shout, followed by another and another, until, at last, the man stationed next to him repeated the signal. Then they moved forward, each trying to obey the orders to march straight ahead.

For some time, nothing was heard save the shouts of the men, and then Charlie made out some distant shots, far in the wood, and guessed that some animals were trying to break through the lines. Then he heard the sound of firing directly in front of him. This continued for some time, occasionally single shots being heard, but more often shots in close succession. Louder and louder grew the shouting, as the men closed in towards a common point, and, in half an hour after the signal had been given, all met.

"What sport have you had, father?" Harry asked, as he came up to Captain Jervoise.

"We killed seventeen wolves and four bears, with, what is more important, six stags. I do not know whether we are going to have another beat."

It soon turned out that this was the king's intention, and the troops marched along the edge of the forest. Charlie was in the front of his company, the king with the cavalry a few hundred yards ahead, when, from a dip of ground on the right, a large body of horsemen suddenly appeared.

"Russians!" Captain Jervoise exclaimed, and shouted to the men, who were marching at ease, to close up.

The king did not hesitate a moment, but, at the head of his fifty cavalry, charged right down upon the Russians, who were at least five hundred strong. The little body disappeared in the melee, and then seemed to be swallowed up.

"Keep together, shoulder to shoulder, men. Double!" and the company set off at a run.

When they came close to the mass of horsemen, they poured in a volley, and then rushed forward, hastily fitting the short pikes they carried into their musket barrels; for, as yet, the modern form of bayonets was not used. The Russians fought obstinately, but the infantry pressed their

Comments (0)