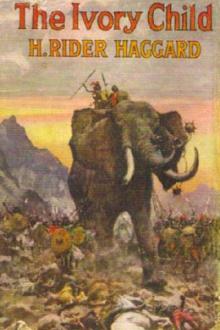

The Ivory Child by H. Rider Haggard (best contemporary novels TXT) 📕

- Author: H. Rider Haggard

- Performer: -

Book online «The Ivory Child by H. Rider Haggard (best contemporary novels TXT) 📕». Author H. Rider Haggard

Thus we journeyed in the centre of a square whence any escape would have been impossible, for I forgot to say that our keepers Har�t and Mar�t rode exactly behind us, at such a distance that we could call to them if we wished.

At first I found this method of travelling very tiring, as does everyone who is quite unaccustomed to camel-back. Indeed the swing and the jolt of the swift creature beneath me seemed to wrench my bones asunder to such an extent that at the beginning I had once or twice to be lifted from the saddle when, after hours of torture, at length we camped for the night. Poor Savage suffered even more than I did, for the motion reduced him to a kind of jelly. Ragnall, however, who I think had ridden camels before, felt little inconvenience, and the same may be said of Hans, who rode in all sorts of positions, sometimes sideways like a lady, and at others kneeling on the saddle like a monkey on a barrel-organ. Also, being very light and tough as rimpis, the swaying motion did not seem to affect him.

By degrees all these troubles left us to such an extent that I could cover my fifty miles a day, more or less, without even feeling tired. Indeed I grew to like the life in that pure and sparkling desert air, perhaps because it was so restful. Day after day we journeyed on across the endless, sandy plain, watching the sun rise, watching it grow high, watching it sink again. Night after night we ate our simple food with appetite and slept beneath the glittering stars till the new dawn broke in glory from the bosom of the immeasurable East.

We spoke but little during all this time. It was as though the silence of the wilderness had got hold of us and sealed our lips. Or perhaps each of us was occupied with his own thoughts. At any rate I know that for my part I seemed to live in a kind of dreamland, thinking of the past, reflecting much upon the innumerable problems of this passing show called life, but not paying much heed to the future. What did the future matter to me, who did not know whether I should have a share of it even for another month, or week, or day, surrounded as I was by the shadow of death? No, I troubled little as to any earthly future, although I admit that in this oasis of calm I reflected upon that state where past, present and future will all be one; also that those reflections, which were in their essence a kind of unshaped prayer, brought much calm to my spirit.

With the regiment of escort we had practically no communication; I think that they had been forbidden to talk to us. They were a very silent set of men, finely-made, capable persons, of an Arab type, light rather than dark in colour, who seemed for the most part to communicate with each other by signs or in low-muttered words. Evidently they looked upon Har�t and Mar�t with great veneration, for any order which either of these brethren gave, if they were brethren, was obeyed without dispute or delay. Thus, when I happened to mention that I had lost a pocket-knife at one of our camping-places two days’ journey back, three of them, much against my wish, were ordered to return to look for it, and did so, making no question. Eight days later they rejoined us much exhausted and having lost a camel, but with the knife, which they handed to me with a low bow; and I confess that I felt ashamed to take the thing.

Nor did we exchange many further confidences with Har�t and Mar�t. Up to the time of our arrival at the boundaries of the Kendah country, our only talk with them was of the incidents of travel, of where we should camp, of how far it might be to the next water, for water-holes or old wells existed in this desert, of such birds as we saw, and so forth. As to other and more important matters a kind of truce seemed to prevail. Still, I observed that they were always studying us, and especially Lord Ragnall, who rode on day after day, self-absorbed and staring straight in front of him as though he looked at something we could not see.

Thus we covered hundreds of miles, not less than five hundred at the least, reckoning our progress at only thirty miles a day, including stoppages. For occasionally we stopped at the water-holes or small oases, where the camels drank and rested. Indeed, these were so conveniently arranged that I came to the conclusion that once there must have been some established route running across these wastelands to the south, of which the traditional knowledge remained with the Kendah people. If so, it had not been used for generations, for save those of one or two that had died on the outward march, we saw no skeletons of camels or other beasts, or indeed any sign of man. The place was an absolute wilderness where nothing lived except a few small mammals at the oases and the birds that passed over it in the air on their way to more fertile regions. Of these, by the way, I saw many that are known both to Europe and Africa, especially ducks and cranes; also storks that, for aught I can say, may have come from far-off, homely Holland.

At last the character of the country began to change. Grass appeared on its lower-lying stretches, then bushes, then occasional trees and among the trees a few buck. Halting the caravan I crept out and shot two of these buck with a right and left, a feat that caused our grave escort to stare in a fashion which showed me that they had never seen anything of the sort done before.

That night, while we were eating the venison with relish, since it was the first fresh meat that we had tasted for many a day, I observed that the disposition of our camp was different from its common form. Thus it was smaller and placed on an eminence. Also the camels were not allowed to graze where they would as usual, but were kept within a limited area while their riders were arranged in groups outside of them. Further, the stores were piled near our tents, in the centre, with guards set over them. I asked Har�t and Mar�t, who were sharing our meal, the reason of these alterations.

“It is because we are on the borders of the Kendah country,” answered old Har�t. “Four days’ more march will bring us there, Macumazana.”

“Then why should you take precautions against your own people? Surely they will welcome you.”

“With spears perhaps. Macumazana, learn that the Kendah are not one but two people. As you may have heard before, we are the White Kendah, but there are also Black Kendah who outnumber us many times over, though in the beginning we from the north conquered them, or so says our history. The White Kendah have their own territory; but as there is no other road, to reach it we must pass through that of the Black Kendah, where it is always possible that we may be attacked, especially as we bring strangers into the land.”

“How is it then that the Black Kendah allow you to live at all, Har�t, if they are so much the more numerous?”

“Because of fear, Macumazana. They fear our wisdom and the decrees of the Heavenly Child spoken through the mouth of its oracle, which, if it is offended, can bring a curse upon them. Still, if they find us outside our borders they may kill us, if they can, as we may kill them if we find them within our borders.”

“Indeed, Har�t. Then it looks to me as though there were a war breeding between you.”

“A war is breeding, Macumazana, the last great war in which either the White Kendah or the Black Kendah must perish. Or perhaps both will die together. Maybe that is the real reason why we have asked you to be our guest, Macumazana,” and with their usual courteous bows, both of them rose and departed before I could reply.

“You see how it stands,” I said to Ragnall. “We have been brought here to fight for our friends, Har�t, Mar�t and Co., against their rebellious subjects, or rather the king who reigns jointly with them.”

“It looks like it,” he replied quietly, “but doubtless we shall find out the truth in time and meanwhile speculation is no good. Do you go to bed, Quatermain, I will watch till midnight and then wake you.”

That night passed in safety. Next day we marched before the dawn, passing through country that grew continually better watered and more fertile, though it was still open plain but sloping upwards ever more steeply. On this plain I saw herds of antelopes and what in the distance looked like cattle, but no human being. Before evening we camped where there was good water and plenty of food for the camels.

While the camp was being set Har�t came and invited us to follow him to the outposts, whence he said we should see a view. We walked with him, a matter of not more than a quarter of a mile to the head of that rise up which we had been travelling all day, and thence perceived one of the most glorious prospects on which my eyes have fallen in all great Africa. From where we stood the land sloped steeply for a matter of ten or fifteen miles, till finally the fall ended in a vast plain like to the bottom of a gigantic saucer, that I presume in some far time of the world’s history was once an enormous lake. A river ran east and west across this plain and into it fell tributaries. Far beyond this river the contours of the country rose again till, many, many miles away, there appeared a solitary hill, tumulus-shaped, which seemed to be covered with bush.

Beyond and surrounding this hill was more plain which with the aid of my powerful glasses was, we could see, bordered at last by a range of great mountains, looking like a blue line pencilled across the northern distance. To the east and west the plain seemed to be illimitable. Obviously its soil was of a most fertile character and supported numbers of inhabitants, for everywhere we could see their kraals or villages. Much of it to the west, however, was covered with dense forest with, to all appearance, a clearing in its midst.

“Behold the land of the Kendah,” said Har�t. “On this side of the River Tava live the Black Kendah, on the farther side, the White Kendah.”

“And what is that hill?”

“That is the Holy Mount, the Home of the Heavenly Child, where no man may set foot”—here he looked at us meaningly—“save the priests of the Child.”

“What happens to him if he does?” I asked.

“He dies, my Lord Macumazana.”

“Then it is guarded, Har�t?”

“It is guarded, not with mortal weapons, Macumazana, but by the spirits that watch over the Child.”

As he would say no more on this interesting matter, I asked him as to the numbers of the Kendah people, to which he replied that the Black Kendah might number twenty thousand men of arm-bearing age, but the White Kendah not more than two thousand.

“Then no wonder you want spirits to guard your Heavenly Child,” I remarked, “since

Comments (0)