The Gun-Brand by James B. Hendryx (thriller book recommendations .TXT) 📕

- Author: James B. Hendryx

- Performer: -

Book online «The Gun-Brand by James B. Hendryx (thriller book recommendations .TXT) 📕». Author James B. Hendryx

Daylight softly dimmed the yellow lamplight of the room. The girl arose, and, after a hurried glance at the sleeping Ripley, bathed her eyes in cold water and passed into the kitchen, where Big Lena was busy in the preparation of breakfast.

"Send LeFroy to me at once!" she ordered, and five minutes later, when the man stood before her, she ordered him to summon all of MacNair's Indians.

The man shifted his weight uneasily from one foot to the other as he

Up on Snare Lake the men to whom Lapierre had passed the word had taken possession of MacNair's burned and abandoned fort, and there the leader had joined them after stopping at Fort McMurray to tip off to Ripley and Craig the bit of evidence that he hoped would clinch the case against MacNair. More men joined the Snare Lake stampede—flat-faced breeds from the lower Mackenzie, evil-visaged rivermen from the country of the Athabasca and the Slave, and the renegade white men who were Lapierre's underlings.

By dog-train and on foot they came, dragging their outfits behind them, and in the eyes of each was the gleam of the greed of gold. The few cabins which had escaped the conflagration had been pre-empted by the first-comers, while the later arrivals pitched their tents and shelter tarps close against the logs of the unburned portion of MacNair's stockade.

At the time of Lapierre's arrival the colony had assumed the aspect of a typical gold camp. The drifted snow had been removed from MacNair's diggings, and the night-fires that thawed out the gravel glared red and illuminated the clearing with a ruddy glow in which the dumps loomed black and ugly, like unclean wens upon the white surface of the trampled snow.

Lapierre, a master of organization, saw almost at the moment of his arrival that the gold-camp system of two-man partnerships could be vastly improved upon. Therefore, he formed the men into shifts: eight hours in the gravel and tending the fires, eight hours chopping cord-wood and digging in the ruins of MacNair's storehouse for the remains of unburned grub, and eight hours' rest. Always night and day, the seemingly tireless leader moved about the camp encouraging, cursing, bullying, urging; forcing the utmost atom of man-power into the channels of greatest efficiency. For well the quarter-breed knew that his tenure of the Snare Lake diggings was a tenure wholly by sufferance of circumstances—over which he, Lapierre, had no control.

With MacNair safely lodged in the Fort Saskatchewan jail, he felt safe from interference, at least until late in the spring. This would allow plenty of time for the melting snows to furnish the water necessary for the cleaning up of the dumps. After that the fate of his colony hung upon the decision of a judge somewhere down in the provinces. Thus Lapierre crowded his men to the utmost, and the increasing size of the black dump-heaps bespoke a record-breaking clean-up when the waters of the melting snow should be turned into sluices in the spring.

With his mind easy in his fancied security, and in order that every moment of time and every ounce of man-power should be devoted to the digging of gold, Lapierre had neglected to bring his rifles and ammunition from the Lac du Mort rendezvous and from the storehouse of Chloe Elliston's school. An omission for which he cursed himself roundly upon an evening, early in February when an Indian, gaunt and wide-eyed from the strain of a forced snow-trail, staggered from the black shadow of the bush into the glare of the blazing night-fires, and in a frenzied gibberish of jargon proclaimed that Bob MacNair had returned to the Northland. And not only that he had returned, but had visited Lac du Mort in company with a man of the Mounted.

At first Lapierre flatly refused to credit the Indian's yarn, but when upon pain of death the man refused to alter his statement, and added the information that he himself had fired at MacNair from the shelter of a snow-ridden spruce, and that just as he pulled the trigger the man of the soldier-police had intervened and stopped the speeding bullet, Lapierre knew that the Indian spoke the truth.

In the twinkling of an eye the quarter-breed realized the extreme danger of his position. His wrath knew no bounds. Up and down he raged in his fury, cursing like a madman, while all about him—blaming, reviling, advising—cursed the men of his ill-favoured crew. For not a man among them but knew that somewhere someone had blundered. And for some inexplicable reason their situation had suddenly shifted from comparative security to extreme hazard. They needed not to be told that with MacNair at large in the Northland their lives hung by a slender thread. For at that very moment Brute MacNair was, in all probability, upon the Yellow Knife leading his armed Indians toward Snare Lake.

In addition to this was the certain knowledge that the vengeance of the Mounted would fall in full measure upon the heads of all who were in any way associated with Pierre Lapierre. An officer had been shot, and the men of Lapierre were outlawed from Ungava to the Western sea. The intricate system had crumbled in the batting of an eye. Else why should a man of the Mounted have been found before the barricade of the Bastile du Mort in company with Brute MacNair?

The quick-witted Lapierre was the first to recover from the shock of the stunning blow. Leaping onto the charred logs of MacNair's storehouse, he called loudly to his men, who in a panic were wildly throwing their outfits onto sleds. Despite their mad haste they crowded close and listened to the words of the man upon whose judgment they had learned to rely, and from whose dreaded "dismissal from service" they had cowered in fear. They swarmed about Lapierre a hundred strong, and his voice rang harsh.

"You dogs! You canaille!" he cried, and they shrank from the baleful glare of his black eyes. "What would you do? Where would you go? Do you think that, single-handed, you can escape from MacNair's Indians, who will follow your trails like hounds and kill you as they would kill a snared rabbit? I tell you your trails will be short. A dead man will lie at the end of each. But even if you succeed in escaping the Indians, what, then, of the Mounted? One by one, upon the rivers and lakes of the Northland, upon wide snow-steeps of the barren grounds, even to the shores of the frozen sea, you will be hunted and gathered in. Or you will be shot like dogs, and your bones left to crunch in the jaws of the wolf-pack. We are outlaws, all! Not a man of us will dare show his face in any post or settlement or city in all Canada."

The men shrank before the words, for they knew them to be true. Again the leader was speaking, and hope gleamed in fear-strained eyes.

"We have yet one chance; I, Pierre Lapierre, have not played my last card. We will stand or fall together! In the Bastile du Mort are many rifles, and ammunition and provisions for half a year. Once behind the barricade, we shall be safe from any attack. We can defy MacNair's Indians and stand off the Mounted until such time as we are in a position to dictate our own terms. If we stand man to man together, we have everything to gain and nothing to lose. We are outlawed, every one. There is no turning back!"

Lapierre's bold assurance averted the threatened panic, and with a yell the men fell to work packing their outfits for the journey to Lac du Mort. The quarter-breed despatched scouts to the southward to ascertain the whereabouts of MacNair, and, if possible, to find out whether or not the officer of the Mounted had been killed by the shot of the Indian.

At early dawn the outfit crossed Snare Lake and headed for Lac du Mort by way of Grizzly Bear, Lake Mackay, and Du Rocher. Upon the evening of the fourth day, when they threaded the black-spruce swamp and pulled wearily into the fort on Lac du Mort, Lapierre found a scout awaiting him with the news that MacNair had headed northward with his Indians, and that LeFroy was soon to start for Fort Resolution with the wounded man of the Mounted. Whereupon he selected the fastest and freshest dog-team available and, accompanied by a half-dozen of his most trusted lieutenants, took the trail for Chloe Elliston's school on-the Yellow Knife, after issuing orders as to the conduct of defence in case of an attack by MacNair's Indians.

Affairs at the school were at a standstill. From a busy hive of activity, with the women and children showing marked improvement at their tasks, and the men happy in the felling of logs and the whip-sawing of lumber, the settlement had suddenly slumped into a disorganized hodge-podge of unrest and anxiety. MacNair's Indians had followed him into the North; their women and children brooded sullenly, and a feeling of unrest and expectancy pervaded the entire colony.

Among the inmates of the cottage the condition was even worse. With Harriet Penny hysterical and excited, Big Lena more glum and taciturn than usual, the Louchoux girl cowering in mortal dread of impending disaster, and Chloe herself disgusted, discouraged, nursing in her heart a consuming rage against Brute MacNair, the man who had wrought the harm, and who had been her evil genius since she had first set foot into the North.

Upon the afternoon of the day she despatched LeFroy to Fort Resolution with the wounded officer of the Mounted, Chloe stood at her little window gazing out over the wide sweep of the river and wondering how it all would end. Would MacNair find Lapierre, and would he kill him? Or would the Mounted heed the urgent appeal she despatched in care of LeFroy and arrive in time to recapture MacNair before he came upon his victim?

"If I only knew where to find him," she muttered, "I could warn him of his danger."

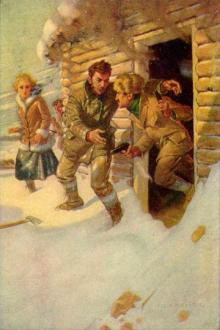

The next moment her eyes widened with amazement, and she pressed her face close against the glass; across the clearing from the direction of the river dashed a dog-team, with three men running before and three behind, while upon the sled, jaunty and smiling, and debonair as ever, sat Pierre Lapierre himself. With a flourish he swung the dogs up to the tiny veranda and stepped from the sled, and the next moment Chloe found herself standing in the little living-room with Lapierre bowing low over her hand. Harriet Penny was in the schoolhouse; the Louchoux girl was helping Big Lena in the kitchen, and for the first time in many moons Chloe Elliston felt glad that she was alone with Lapierre.

When at length she removed her hand from his grasp she stood for some moments regarding the clean-cut lines of his features, and then she smiled as she noted the trivial fact that he had removed his hat, and that he stood humbly before her with bared head. A great surge of feeling rushed over her as she realized how clean and good—how perfect this man seemed in comparison with the hulking brutality of MacNair. She motioned him to a seat beside the table, and drawing her chair close to his side, poured into his attentive and sympathetic

Comments (0)