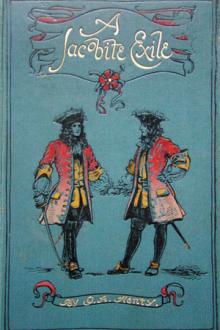

A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕». Author G. A. Henty

"That is true enough, Sir Marmaduke," one of the others said. "The question is: how long has this been going on?"

Sir Marmaduke looked at Charlie.

"I know nothing about it, sir. Till now, I have not had the slightest suspicion of this man. It occurred to me, this afternoon, that it might be possible for anyone to hear what was said inside the room, by listening at the windows; and that this shrubbery would form a very good shelter for an eavesdropper. So I thought, this evening I would take up my place here, to assure myself that there was no traitor in the household. I had been here but five minutes when the fellow stole quietly up, and placed his ear at the opening of the casement, and you may be sure that I gave him no time to listen to what was being said."

"Well, we had better go in," Sir Marmaduke said. "There is no fear of our being overheard this evening.

"Charlie, do you take old Banks aside, and tell him what has happened, and then go with him to the room where that fellow slept, and make a thorough search of any clothes he may have left behind, and of the room itself. Should you find any papers or documents, you will, of course, bring them down to me."

But the closest search, by Charlie and the old butler, produced no results. Not a scrap of paper of any kind was found, and Banks said that he knew the man could neither read nor write.

The party below soon broke up, considerable uneasiness being felt, by all, at the incident of the evening. When the last of them had left, Charlie was sent for.

"Now, then, Charlie, let me hear how all this came about. I know that all you said about what took place at the window is perfectly true; but, even had you not said so, I should have felt there was something else. What was it brought you to that window? Your story was straight-forward enough, but it was certainly singular your happening to be there, and I fancy some of our friends thought that you had gone round to listen, yourself. One hinted as much; but I said that was absurd, for you were completely in my confidence, and that, whatever peril and danger there might be in the enterprise, you would share them with me."

"It is not pleasant that they should have thought so, father, but that is better than that the truth should be known. This is how it happened;" and he repeated what Ciceley had told him in the garden.

"So the worthy Master John Dormay has set a spy upon me," Sir Marmaduke said, bitterly. "I knew the man was a knave--that is public property--but I did not think that he was capable of this. Well, I am glad that, at any rate, no suspicion can fall upon Ciceley in the matter; but it is serious, lad, very serious. We do not know how long this fellow has been prying and listening, or how much he may have learnt. I don't think it can be much. We talked it over, and my friends all agreed with me that they do not remember those curtains having been drawn before. To begin with, the evenings are shortening fast, and, at our meeting last week, we finished our supper by daylight; and, had the curtains been drawn, it would have been noticed, for we had need of light before we finished. Two of the gentlemen, who were sitting facing the window, declared that they remembered distinctly that it was open. Mr. Jervoise says that he thought to himself that, if it was his place, he would have the trees cut away there, for they shut out the light.

"Therefore, although it is uncomfortable to think that there has been a spy in the house, for some months, we have every reason to hope that our councils have not been overheard. Were it otherwise, I should lose no time in making for the coast, and taking ship to France, to wait quietly there until the king comes over."

"You have no documents, father, that the man could have found?"

"None, Charlie. We have doubtless made lists of those who could be relied upon, and of the number of men they could bring with them, but these have always been burned before we separated. Such letters as I have had from France, I have always destroyed as soon as I have read them. Perilous stuff of that sort should never be left about. No; they may ransack the place from top to bottom, and nothing will be found that could not be read aloud, without harm, in the marketplace of Lancaster.

"So now, to bed, Charlie. It is long past your usual hour."

Chapter 2: Denounced."Charlie," Sir Marmaduke said on the following morning, at breakfast, "it is quite possible that that villain who acted as spy, and that other villain who employed him--I need not mention names--may swear an information against me, and I may be arrested, on the charge of being concerned in a plot. I am not much afraid of it, if they do. The most they could say is that I was prepared to take up arms, if his majesty crossed from France; but, as there are thousands and thousands of men ready to do the same, they may fine me, perhaps, but I should say that is all. However, what I want to say to you is, keep out of the way, if they come. I shall make light of the affair, while you, being pretty hot tempered, might say things that would irritate them, while they could be of no assistance to me. Therefore, I would rather that you were kept out of it, altogether. I shall want you here. In my absence, there must be somebody to look after things.

"Mind that rascal John Dormay does not put his foot inside the house, while I am away. That fellow is playing some deep game, though I don't quite know what it is. I suppose he wants to win the goodwill of the authorities, by showing his activity and zeal; and, of course, he will imagine that no one has any idea that he has been in communication with this spy. We have got a hold over him, and, when I come back, I will have it out with him. He is not popular now, and, if it were known that he had been working against me, his wife's kinsman, behind my back, my friends about here would make the country too hot to hold him."

"Yes, father; but please do not let him guess that we have learnt it from Ciceley. You see, that is the only way we know about it."

"Yes, you are right there. I will be careful that he shall not know the little maid has anything to do with it. But we will think of that, afterwards; maybe nothing will come of it, after all. But, if anything does, mind, my orders are that you keep away from the house, while they are in it. When you come back, Banks will tell you what has happened.

"You had better take your horse, and go for a ride now. Not over there, Charlie. I know, if you happened to meet that fellow, he would read in your face that you knew the part he had been playing, and, should nothing come of the business, I don't want him to know that, at present. The fellow can henceforth do us no harm, for we shall be on our guard against eavesdroppers; and, for the sake of cousin Celia and the child, I do not want an open breach. I do not see the man often, myself, and I will take good care I don't put myself in the way of meeting him, for the present, at any rate. Don't ride over there today."

"Very well, father. I will ride over and see Harry Jervoise. I promised him that I would come over one day this week."

It was a ten-mile ride, and, as he entered the courtyard of Mr. Jervoise's fine old mansion, he leapt off his horse, and threw the reins over a post. A servant came out.

"The master wishes to speak to you, Master Carstairs."

"No ill news, I hope, Charlie?" Mr. Jervoise asked anxiously, as the lad was shown into the room, where his host was standing beside the carved chimney piece.

"No, sir, there is nothing new. My father thought that I had better be away today, in case any trouble should arise out of what took place yesterday, so I rode over to see Harry. I promised to do so, one day this week."

"That is right. Does Sir Marmaduke think, then, that he will be arrested?"

"I don't know that he expects it, sir, but he says that it is possible."

"I do not see that they have anything to go upon, Charlie. As we agreed last night, that spy never had any opportunity of overhearing us before, and, certainly, he can have heard nothing yesterday. The fellow can only say what many people know, or could know, if they liked; that half a dozen of Sir Marmaduke's friends rode over to take supper with him. They can make nothing out of that."

"No, sir; and my father said that, at the worst, it could be but the matter of a fine."

"Quite so, lad; but I don't even see how it could amount to that. You will find Harry somewhere about the house. He has said nothing to me about going out."

Harry Jervoise was just the same age as Charlie, and was his greatest friend. They were both enthusiastic in the cause of the Stuarts, equally vehement in their expressions of contempt for the Dutch king, equally anxious for the coming of him whom they regarded as their lawful monarch. They spent the morning together, as usual; went first to the stables and patted and talked to their horses; then they played at bowls on the lawn; after which, they had a bout of sword play; and, having thus let off some of their animal spirits, sat down and talked of the glorious times to come, when the king was to have his own again.

Late in the afternoon, Charlie mounted his horse and rode for home. When within half a mile of the house, a man stepped out into the road in front of him.

"Hullo, Banks, what is it? No bad news, I hope?"

And he leapt from his horse, alarmed at the pallor of the old butler's face.

"Yes, Master Charles, I have some very bad news, and have been waiting for the last two hours here, so as to stop you going to the house."

"Why shouldn't I go to the house?"

"Because there are a dozen soldiers, and three or four constables there."

"And my father?"

"They have taken him away."

"This is bad news, Banks; but I know that he thought that it might be so. But it will not be very serious; it is only a question of a fine," he said.

The butler shook his head, sadly.

"It is worse than that, Master Charles. It is worse than you think."

"Well, tell me all about it, Banks," Charlie said, feeling much alarmed at the old man's manner.

"Well, sir, at three this afternoon, two magistrates, John Cockshaw and William Peters--"

("Both bitter Whigs," Charlie put in.)

"--Rode up to the door. They had with them six constables, and twenty troopers."

"There were enough of them, then," Charlie said. "Did they think my father was going to arm you all, and defend the place?"

"I don't know, sir, but that is the number that came. The magistrates, and the constables, and four of the soldiers came into the

Comments (0)