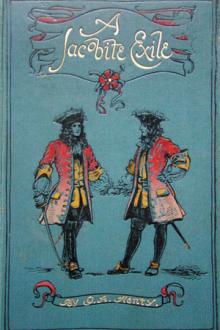

A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕

- Author: G. A. Henty

- Performer: -

Book online «A Jacobite Exile by G. A. Henty (reading books for 4 year olds txt) 📕». Author G. A. Henty

Finding the search ineffectual, Charlie proposed that they should go for a long walk along the north road.

"I am tired of staring every man I meet in the face, Harry. And I should like, for once, to be able to throw it all off and take a good walk together, as we used to do in the old days. We will go eight or ten miles out, stop at some wayside inn for refreshments, and then come back here for the night, and start back again for town tomorrow."

Harry at once agreed, and, taking their hats, they started.

They did not hurry themselves, and, carefully avoiding all mention of the subject that had occupied their thoughts for weeks, they chatted over their last campaign, their friends in the Swedish camp, and the course that affairs were likely to take. After four hours' walking they came to a small wayside inn, standing back twenty or thirty yards from the road.

"It is a quiet-looking little place," Charlie said, "and does but a small trade, I should say. However, no doubt they can give us some bread and cheese, and a mug of ale, which will last us well enough till we get back to Barnet."

The landlord placed what they demanded before them, and then left the room again, replying by a short word or two to their remarks on the weather.

"A surly ill-conditioned sort of fellow," Harry said.

"It may be, Harry, that badness of trade has spoiled his temper. However, so long as his beer is good, it matters little about his mood."

They had finished their bread and cheese, and were sitting idly, being in no hurry to start on their way back, when a man on horseback turned off from the road and came up the narrow lane in which the house stood. As Charlie, who was facing that way, looked at him he started, and grasped Harry's arm.

"It is our man," he said. "It is Nicholson himself! To think of our searching all London, these weeks past, and stumbling upon him here."

The man stopped at the door, which was at once opened by the landlord.

"All right, I suppose, landlord?" the man said, as he swung himself from his horse.

"There is no one here except two young fellows, who look to me as if they had spent their last penny in London, and were travelling down home again."

He spoke in a lowered voice, but the words came plainly enough to the ears of the listeners within. Another word or two was spoken, and then the landlord took the horse and led it round to a stable behind, while its rider entered the room. He stopped for a moment at the open door of the taproom, and stared at the two young men, who had just put on their hats again. They looked up carelessly, and Harry said:

"Fine weather for this time of year."

The man replied by a grunt, and then passed on into the landlord's private room.

"That is the fellow, sure enough, Charlie," Harry said, in a low tone. "I thought your eyes might have deceived you, but I remember his face well. Now what is to be done?"

"We won't lose sight of him again," Charlie said. "Though, if we do, we shall know where to pick up his traces, for he evidently frequents this place. I should say he has taken to the road. There were a brace of pistols in the holsters. That is how it is that we have not found him before. Well, at any rate, there is no use trying to make his acquaintance here. The first question is, will he stay here for the night or not--and if he does not, which way will he go?"

"He came from the north," Harry said. "So if he goes, it will be towards town."

"That is so. Our best plan will be to pay our reckoning and start. We will go a hundred yards or so down the road, and then lie down behind a hedge, so as to see if he passes. If he does not leave before nightfall, we will come up to the house and reconnoitre. If he does not leave by ten, he is here for the night, and we must make ourselves as snug as we can under a stack. The nights are getting cold, but we have slept out in a deal colder weather than this. However, I fancy he will go on. It is early for a man to finish a journey. If he does, we must follow him, and keep him in sight, if possible."

Two hours later they saw, from their hiding place, Nicholson ride out from the lane. He turned his horse's head in their direction.

"That is good," Charlie said. "If he is bound for London, we shall be able to get into his company somehow; but if he had gone up to some quiet place north, we might have had a lot of difficulty in getting acquainted with him."

As soon as the man had ridden past they leapt to their feet, and, at a run, kept along the hedge. He had started at a brisk trot, but when, a quarter of a mile on, they reached a gate, and looked up the road after him, they saw to their satisfaction that the horse had already fallen into a walk.

"He does not mean to go far from Barnet," Charlie exclaimed. "If he had been bound farther, he would have kept on at a trot. We will keep on behind the hedges as long as we can. If he were to look back and see us always behind him, he might become suspicious."

They had no difficulty in keeping up with the horseman. Sometimes, when they looked out, he was a considerable distance ahead, having quickened his pace; but he never kept that up long, and by brisk running, and dashing recklessly through the hedges running at right angles to that they were following, they soon came up to him again.

Once, he had gone so far ahead that they took to the road, and followed it until he again slackened his speed. They thus kept him in sight till they neared Barnet.

"We can take to the road now," Harry said. "Even if he should look round, he will think nothing of seeing two men behind him. We might have turned into it from some by-lane. At any rate, we must chance it. We must find where he puts up for the night."

Chapter 17: The North Coach.Barnet was then, as now, a somewhat straggling place. Soon after entering it, the horseman turned off from the main road. His pursuers were but fifty yards behind him, and they kept him in sight until, after proceeding a quarter of a mile, he stopped at a small tavern, where he dismounted, and a boy took his horse and led it round by the side of the house.

"Run to earth!" Harry said exultantly. "He is not likely to move from there tonight."

"At any rate, he is safe for a couple of hours," Charlie said. "So we will go to our inn, and have a good meal. By that time it will be quite dark, and we will have a look at the place he has gone into; and if we can't learn anything, we must watch it by turns till midnight. We will arrange, at the inn, to hire a horse. One will be enough. He only caught a glimpse of us at that inn, and certainly would not recognize one of us, if he saw him alone. The other can walk."

"But which way, Charlie? He may go back again." "It is hardly likely he came here merely for the pleasure of stopping the night at that little tavern. I have no doubt he is bound for London. You shall take the horse, Harry, and watch until he starts, and then follow him, just managing to come up close to him as he gets into town. I will start early, and wait at the beginning of the houses, and it is hard if one or other of us does not manage to find out where he hides."

They had no difficulty in arranging with the landlord for a horse, which was to be left in a stable he named in town. They gave him a deposit, for which he handed them a note, by which the money was to be returned to them by the stable keeper, on their handing over the horse in good condition.

After the meal they sallied out again, and walked to the tavern, which was a small place standing apart from other houses. There was a light in the taproom, but they guessed that here, as at the other stopping place, the man they wanted would be in a private apartment. Passing the house, they saw a light in a side window, and, noiselessly opening a little wicket gate, they stole into the garden. Going a short distance back from the window, so that the light should not show their faces, they looked in, and saw the man they sought sitting by the fire, with a table on which stood a bottle and two glasses beside him, and another man facing him.

"Stay where you are, Harry. I will steal up to the window, and find out whether I can hear what they are saying."

Stooping close under the window, he could hear the murmur of voices, but could distinguish no words. He rejoined his companion.

"I am going to make a trial to overhear them, Harry, and it is better that only one of us should be here. You go back to the inn, and wait for me there."

"What are you going to do, Charlie?"

"I am going to throw a stone through the lower part of the window. Then I shall hide. They will rush out, and when they can find no one, they will conclude that the stone was thrown by some mischievous boy going along the road. When all is quiet again I will creep up to the window, and it will be hard if I don't manage to learn something of what they are saying."

The plan was carried out, and Charlie, getting close up to the window, threw a stone through one of the lowest of the little diamond-shaped panes. He heard a loud exclamation of anger inside, and then sprang away and hid himself at the other end of the garden. A moment later he heard loud talking in the road, and a man with a lantern came round to the window; but in a few minutes all was quiet again, and Charlie cautiously made his way back to the window, and crouched beneath it. He could hear plainly enough, now, the talk going on within.

"What was I saying when that confounded stone interrupted us?"

"You were saying, captain, that you intended to have a week in London, and then to stop the North coach."

"Yes, I have done well lately, and can afford a week's pleasure. Besides, Jerry Skinlow got a bullet in his shoulder, last week, in trying to stop a carriage on his own account, and Jack Mercer's mare is laid up lame, and it wants four to stop a coach neatly. Jack Ponsford is in town. I shall bring him out with me."

"I heard that you were out of luck a short time ago."

"Yes, everything seemed against me. My horse was shot, and, just at the time, I had been having a bad run at the tables and had lost my last stiver. I was in hiding for a fortnight at one of the cribs; for they had got a description of me from an old gentleman, who, with his wife and daughter, I had eased of their money and watches. It was a stupid business. I dropped a valuable diamond ring on the ground, and in groping about for it my mask came off, and, like a fool, I stood

Comments (0)