A Tale of Two Cities by Dave Mckay, Charles Dickens (sight word books TXT) 📕

- Author: Dave Mckay, Charles Dickens

Book online «A Tale of Two Cities by Dave Mckay, Charles Dickens (sight word books TXT) 📕». Author Dave Mckay, Charles Dickens

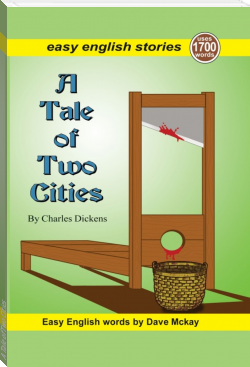

"A Tale of Two Cities" by Charles Dickens, is part of a computerised reading program devised by journalist/author Dave McKay. The program, which paraphrases classic novels, primarily targets people who are learning English as a second language. It enables older students to quickly read classic novels despite having a very limited reading vocabulary. Each book has a number on the cover, showing how many different English words were used in McKay's translation of teh book.

Free e-book «A Tale of Two Cities by Dave Mckay, Charles Dickens (sight word books TXT) 📕» - read online now

Similar e-books:

Comments (0)