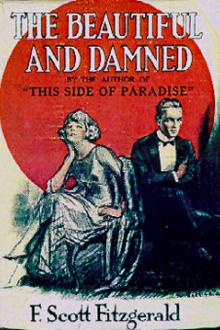

The Beautiful and the Damned by F. Scott Fitzgerald (i like reading books .TXT) 📕

- Author: F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Performer: -

Book online «The Beautiful and the Damned by F. Scott Fitzgerald (i like reading books .TXT) 📕». Author F. Scott Fitzgerald

It is seven-thirty of an August evening. The windows in the living room of the gray house are wide open, patiently exchanging the tainted inner atmosphere of liquor and smoke for the fresh drowsiness of the late hot dusk. There are dying flower scents upon the air, so thin, so fragile, as to hint already of a summer laid away in time. But August is still proclaimed relentlessly by a thousand crickets around the side-porch, and by one who has broken into the house and concealed himself confidently behind a bookcase, from time to time shrieking of his cleverness and his indomitable will.

The room itself is in messy disorder. On the table is a dish of fruit, which is real but appears artificial. Around it are grouped an ominous assortment of decanters, glasses, and heaped ash-trays, the latter still raising wavy smoke-ladders into the stale air, the effect on the whole needing but a skull to resemble that venerable chromo, once a fixture in every “den,” which presents the appendages to the life of pleasure with delightful and awe-inspiring sentiment.

After a while the sprightly solo of the supercricket is interrupted rather than joined by a new sound—the melancholy wail of an erratically fingered flute. It is obvious that the musician is practising rather than performing, for from time to time the gnarled strain breaks off and, after an interval of indistinct mutterings, recommences.

Just prior to the seventh false start a third sound contributes to the subdued discord. It is a taxi outside. A minute’s silence, then the taxi again, its boisterous retreat almost obliterating the scrape of footsteps on the cinder walk. The door-bell shrieks alarmingly through the house.

From the kitchen enters a small, fatigued Japanese, hastily buttoning a servant’s coat of white duck. He opens the front screen-door and admits a handsome young man of thirty, clad in the sort of well-intentioned clothes peculiar to those who serve mankind. To his whole personality clings a well-intentioned air: his glance about the room is compounded of curiosity and a determined optimism; when he looks at Tana the entire burden of uplifting the godless Oriental is in his eyes. His name is FREDERICK E. PARAMORE. He was at Harvard with ANTHONY, where because of the initials of their surnames they were constantly placed next to each other in classes. A fragmentary acquaintance developed—but since that time they have never met.

Nevertheless, PARAMORE enters the room with a certain air of arriving for the evening.

Tana is answering a question.

TANA: (_Grinning with ingratiation_) Gone to Inn for dinnah. Be back half-hour. Gone since ha’ past six.

PARAMORE: (_Regarding the glasses on the table_) Have they company?

TANA: Yes. Company. Mistah Caramel, Mistah and Missays Barnes, Miss Kane, all stay here.

PARAMORE: I see. (_Kindly_) They’ve been having a spree, I see.

TANA: I no un’stan’.

PARAMORE: They’ve been having a fling.

TANA: Yes, they have drink. Oh, many, many, many drink.

PARAMORE: (_Receding delicately from the subject_) “Didn’t I hear the sounds of music as I approached the house”?

TANA:(_With a spasmodic giggle_)Yes, I play.

PARAMORE: One of the Japanese instruments.

(_He is quite obviously a subscriber to the “National Geographic Magazine_.”)

TANA: I play flu-u-ute, Japanese flu-u-ute.

PARAMORE: What song were you playing? One of your Japanese melodies?

TANA:(_His brow undergoing preposterous contraction_) I play train song. How you call?—railroad song. So call in my countree. Like train. It go so-o-o; that mean whistle; train start. Then go so-o-o; that mean train go. Go like that. Vera nice song in my countree. Children song.

PARAMORE: It sounded very nice. (_It is apparent at this point that only a gigantic effort at control restrains Tana from rushing up-stairs for his post cards, including the six made in America_.)

TANA: I fix high-ball for gentleman?

PARAMORE: “No, thanks. I don’t use it”. (_He smiles_.)

(TANA withdraws into the kitchen, leaving the intervening door slightly ajar. From the crevice there suddenly issues again the melody of the Japanese train song—this time not a practice, surely, but a performance, a lusty, spirited performance.

The phone rings. TANA, absorbed in his harmonics, gives no heed, so PARAMORE takes up the receiver.)

PARAMORE: Hello…. Yes…. No, he’s not here now, but he’ll be back any moment…. Butterworth? Hello, I didn’t quite catch the name…. Hello, hello, hello. Hello! … Huh!

(_The phone obstinately refuses to yield up any more sound. Paramore replaces the receiver._

At this point the taxi motif re-enters, wafting with it a second young man; he carries a suitcase and opens the front door without ringing the bell.)

MAURY: (_In the hall_) “Oh, Anthony! Yoho”! (_He comes into the large room and sees_ PARAMORE) How do?

PARAMORE: (_Gazing at him with gathering intensity_) Is this—is this Maury Noble?

MAURY: “That’s it”. (_He advances, smiling, and holding out his hand_) How are you, old boy? Haven’t seen you for years.

(_He has vaguely associated the face with Harvard, but is not even positive about that. The name, if he ever knew it, he has long since forgotten. However, with a fine sensitiveness and an equally commendable charity_ PARAMORE recognizes the fact and tactfully relieves the situation.)

PARAMORE: You’ve forgotten Fred Paramore? We were both in old Unc Robert’s history class.

MAURY: No, I haven’t, Unc—I mean Fred. Fred was—I mean Unc was a great old fellow, wasn’t he?

PARAMORE: (_Nodding his head humorously several times_) Great old character. Great old character.

MAURY: (_After a short pause_) Yes—he was. Where’s Anthony?

PARAMORE: The Japanese servant told me he was at some inn. Having dinner, I suppose.

MAURY: (_Looking at his watch_) Gone long?

PARAMORE: I guess so. The Japanese told me they’d be back shortly.

MAURY: Suppose we have a drink.

PARAMORE: No, thanks. I don’t use it. (_He smiles_.)

MAURY: Mind if I do? (_Yawning as he helps himself from a bottle_) What have you been doing since you left college?

PARAMORE: Oh, many things. I’ve led a very active life. Knocked about here and there. (_His tone implies anything front lion-stalking to organized crime._)

MAURY: Oh, been over to Europe?

PARAMORE: No, I haven’t—unfortunately.

MAURY: I guess we’ll all go over before long.

PARAMORE: Do you really think so?

MAURY: Sure! Country’s been fed on sensationalism for more than two years. Everybody getting restless. Want to have some fun.

PARAMORE: Then you don’t believe any ideals are at stake?

MAURY: Nothing of much importance. People want excitement every so often.

PARAMORE: (_Intently_) It’s very interesting to hear you say that. Now I was talking to a man who’d been over there–-

(_During the ensuing testament, left to be filled in by the reader with such phrases as “Saw with his own eyes,” “Splendid spirit of France,” and “Salvation of civilization,” MAURY sits with lowered eyelids, dispassionately bored._)

MAURY: (_At the first available opportunity_) By the way, do you happen to know that there’s a German agent in this very house?

PARAMORE: (_Smiling cautiously_) Are you serious?

MAURY: Absolutely. Feel it my duty to warn you.

PARAMORE: (_Convinced_) A governess?

MAURY: (_In a whisper, indicating the kitchen with his thumb_) Tana! That’s not his real name. I understand he constantly gets mail addressed to Lieutenant Emile Tannenbaum.

PARAMORE: (_Laughing with hearty tolerance_) You were kidding me.

MAURY: I may be accusing him falsely. But, you haven’t told me what you’ve been doing.

PARAMORE: For one thing—writing.

MAURY: Fiction?

PARAMORE: No. Non-fiction.

MAURY: What’s that? A sort of literature that’s half fiction and half fact?

PARAMORE: Oh, I’ve confined myself to fact. I’ve been doing a good deal of social-service work.

MAURY: Oh!

(_An immediate glow of suspicion leaps into his eyes. It is as though_ PARAMORE had announced himself as an amateur pickpocket.)

PARAMORE: At present I’m doing service work in Stamford. Only last week some one told me that Anthony Patch lived so near.

(_They are interrupted by a clamor outside, unmistakable as that of two sexes in conversation and laughter. Then there enter the room in a body_ ANTHONY, GLORIA, RICHARD CARAMEL, MURIEL KANE, RACHAEL BARNES and RODMAN BARNES, her husband. They surge about MAURY, illogically replying “Fine!” to his general “Hello.” … ANTHONY, meanwhile, approaches his other guest.)

ANTHONY: Well, I’ll be darned. How are you? Mighty glad to see you.

PARAMORE: It’s good to see you, Anthony. I’m stationed in Stamford, so I thought I’d run over. (_Roguishly_) We have to work to beat the devil most of the time, so we’re entitled to a few hours’ vacation.

(_In an agony of concentration_ ANTHONY tries to recall the name. After a struggle of parturition his memory gives up the fragment “Fred,” around which he hastily builds the sentence “Glad you did, Fred!” Meanwhile the slight hush prefatory to an introduction has fallen upon the company. MAURY, who could help, prefers to look on in malicious enjoyment.)

ANTHONY: (_In desperation_) Ladies and gentlemen, this is—this is Fred.

MURIEL: (_With obliging levity_) Hello, Fred!

(RICHARD CARAMEL and PARAMORE greet each other intimately by their first names, the latter recollecting that DICK was one of the men in his class who had never before troubled to speak to him. DICK fatuously imagines that PARAMORE is some one he has previously met in ANTHONY’S house.

The three young women go up-stairs.)

MAURY: (_In an undertone to_ DICK) Haven’t seen Muriel since Anthony’s wedding.

DICK: She’s now in her prime. Her latest is “I’ll say so!”

(ANTHONY struggles for a while with PARAMORE and at length attempts to make the conversation general by asking every one to have a drink.)

MAURY: I’ve done pretty well on this bottle. I’ve gone from “Proof” down to “Distillery.” (_He indicates the words on the label._)

ANTHONY: (_To_ PARAMORE) Never can tell when these two will turn up. Said good-by to them one afternoon at five and darned if they didn’t appear about two in the morning. A big hired touring-car from New York drove up to the door and out they stepped, drunk as lords, of course.

(_In an ecstasy of consideration_ PARAMORE _regards the cover of a book which he holds in his hand. MAURY and_ DICK exchange a glance.)

DICK: (_Innocently, to_ PARAMORE) You work here in town?

PARAMORE: No, I’m in the Laird Street Settlement in Stamford. (_To_ ANTHONY) You have no idea of the amount of poverty in these small Connecticut towns. Italians and other immigrants. Catholics mostly, you know, so it’s very hard to reach them.

ANTHONY: (_Politely_) Lot of crime?

PARAMORE: Not so much crime as ignorance and dirt.

MAURY: That’s my theory: immediate electrocution of all ignorant and dirty people. I’m all for the criminals—give color to life. Trouble is if you started to punish ignorance you’d have to begin in the first families, then you could take up the moving picture people, and finally Congress and the clergy.

PARAMORE: (_Smiling uneasily_) I was speaking of the more fundamental ignorance—of even our language.

MAURY: (_Thoughtfully_) I suppose it is rather hard. Can’t even keep up with the new poetry.

PARAMORE: It’s only when the settlement work has gone on for months that one realizes how bad things are. As our secretary said to me, your finger-nails never seem dirty until you wash your hands. Of course

Comments (0)