The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕

- Author: Bram Stoker

- Performer: -

Book online «The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕». Author Bram Stoker

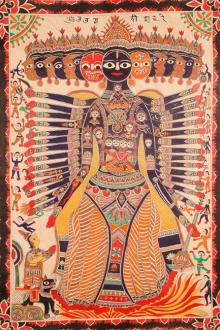

Ra and Osiris in the Boat of the Dead, with the Eye of Sleep, supported

on legs, bending before her; and Harmochis rising in the north. Will

you find that in the British Museum-or Bow Street? Or perhaps your

studies in the Gizeh Museum, or the Fitzwilliam, or Paris, or Leyden, or

Berlin, have shown you that the episode is common in hieroglyphics; and

that this is only a copy. Perhaps you can tell me what that figure of

Ptah-Seker-Ausar holding the Tet wrapped in the Sceptre of Papyrus

means? Did you ever see it before; even in the British Museum, or

Gizeh, or Scotland Yard?”

He broke off suddenly; and then went on in quite a different way:

“Look here! it seems to me that the thick-headed idiot is myself! I beg

your pardon, old fellow, for my rudeness. I quite lost my temper at the

suggestion that I do not know these lamps. You don’t mind, do you?”

The Detective answered heartily:

“Lord, sir, not I. I like to see folks angry when I am dealing with

them, whether they are on my side or the other. It is when people are

angry that you learn the truth from them. I keep cool; that is my

trade! Do you know, you have told me more about those lamps in the past

two minutes than when you filled me up with details of how to identify

them.”

Mr. Corbeck grunted; he was not pleased at having given himself away.

All at once he turned to me and said in his natural way:

“Now tell me how you got them back?” I was so surprised that I said

without thinking:

“We didn’t get them back!” The traveller laughed openly.

“What on earth do you mean?” he asked. “You didn’t get them back! Why,

there they are before your eyes! We found you looking at them when we

came in.” By this time I had recovered my surprise and had my wits

about me.

“Why, that’s just it,” I said. “We had only come across them, by

accident, that very moment!”

Mr. Corbeck drew back and looked hard at Miss Trelawny and myself;

turning his eyes from one to the other as he asked:

“Do you mean to tell me that no one brought them here; that you found

them in that drawer? That, so to speak, no one at all brought them

back?”

“I suppose someone must have brought them here; they couldn’t have come

of their own accord. But who it was, or when, or how, neither of us

knows. We shall have to make inquiry, and see if any of the servants

know anything of it.”

We all stood silent for several seconds. It seemed a long time. The

first to speak was the Detective, who said in an unconscious way:

“Well, I’m damned! I beg your pardon, miss!” Then his mouth shut like

a steel trap.

We called up the servants, one by one, and asked them if they knew

anything of some articles placed in a drawer in the boudoir; but none of

them could throw any light on the circumstance. We did not tell them

what the articles were; or let them see them.

Mr. Corbeck packed the lamps in cotton wool, and placed them in a tin

box. This, I may mention incidentally, was then brought up to the

detectives’ room, where one of the men stood guard over them with a

revolver the whole night. Next day we got a small safe into the house,

and placed them in it. There were two different keys. One of them I

kept myself; the other I placed in my drawer in the Safe Deposit vault.

We were all determined that the lamps should not be lost again.

About an hour after we had found the lamps, Doctor Winchester arrived.

He had a large parcel with him, which, when unwrapped, proved to be the

mummy of a cat. With Miss Trelawny’s permission he placed this in the

boudoir; and Silvio was brought close to it. To the surprise of us all,

however, except perhaps Doctor Winchester, he did not manifest the least

annoyance; he took no notice of it whatever. He stood on the table

close beside it, purring loudly. Then, following out his plan, the

Doctor brought him into Mr. Trelawny’s room, we all following. Doctor

Winchester was excited; Miss Trelawny anxious. I was more than

interested myself, for I began to have a glimmering of the Doctor’s

idea. The Detective was calmly and coldly superior; but Mr. Corbeck,

who was an enthusiast, was full of eager curiosity.

The moment Doctor Winchester got into the room, Silvio began to mew and

wriggle; and jumping out of his arms, ran over to the cat mummy and

began to scratch angrily at it. Miss Trelawny had some difficulty in

taking him away; but so soon as he was out of the room he became quiet.

When she came back there was a clamour of comments:

“I thought so!” from the Doctor.

“What can it mean?” from Miss Trelawny.

“That’s a very strange thing!” from Mr. Corbeck.

“Odd! but it doesn’t prove anything!” from the Detective.

“I suspend my judgment!” from myself, thinking it advisable to say

something.

Then by common consent we dropped the theme—for the present.

In my room that evening I was making some notes of what had happened,

when there came a low tap on the door. In obedience to my summons

Sergeant Daw came in, carefully closing the door behind him.

“Well, Sergeant,” said I, ‘sit down. What is it?”

“I wanted to speak to you, sir, about those lamps.” I nodded and

waited: he went on: “You know that that room where they were found

opens directly into the room where Miss Trelawny slept last night?”

“Yes.”

“During the night a window somewhere in that part of the house was

opened, and shut again. I heard it, and took a look round; but I could

see no sign of anything.”

“Yes, I know that!” I said; “I heard a window moved myself.”

“Does nothing strike you as strange about it, sir?”

“Strange!” I said; “Strange! why it’s all the most bewildering,

maddening thing I have ever encountered. It is all so strange that one

seems to wonder, and simply waits for what will happen next. But what

do you mean by strange?”

The Detective paused, as if choosing his words to begin; and then said

deliberately:

“You see, I am not one who believes in magic and such things. I am for

facts all the time; and I always find in the long-run that there is a

reason and a cause for everything. This new gentleman says these things

were stolen out of his room in the hotel. The lamps, I take it from

some things he has said, really belong to Mr. Trelawny. His daughter,

the lady of the house, having left the room she usually occupies, sleeps

that night on the ground floor. A window is heard to open and shut

during the night. When we, who have been during the day trying to find

a clue to the robbery, come to the house, we find the stolen goods in a

room close to where she slept, and opening out of it!”

He stopped. I felt that same sense of pain and apprehension, which I

had experienced when he had spoken to me before, creeping, or rather

rushing, over me again. I had to face the matter out, however. My

relations with her, and the feeling toward her which I now knew full

well meant a very deep love and devotion, demanded so much. I said as

calmly as I could, for I knew the keen eyes of the skilful investigator

were on me:

“And the inference?”

He answered with the cool audacity of conviction:

“The inference to me is that there was no robbery at all. The goods

were taken by someone to this house, where they were received through a

window on the ground floor. They were placed in the cabinet, ready to

be discovered when the proper time should come!”

Somehow I felt relieved; the assumption was too monstrous. I did not

want, however, my relief to be apparent, so I answered as gravely as I

could:

“And who do you suppose brought them to the house?”

“I keep my mind open as to that. Possibly Mr. Corbeck himself; the

matter might be too risky to trust to a third party.”

“Then the natural extension of your inference is that Mr. Corbeck is a

liar and a fraud; and that he is in conspiracy with Miss Trelawny to

deceive someone or other about those lamps.”

“Those are harsh words, Mr. Ross. They’re so plain-spoken that they

bring a man up standing, and make new doubts for him. But I have to go

where my reason points. It may be that there is another party than Miss

Trelawny in it. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for the other matter that set

me thinking and bred doubts of its own about her, I wouldn’t dream of

mixing her up in this. But I’m safe on Corbeck. Whoever else is in it,

he is! The things couldn’t have been taken without his connivance-if

what he says is true. If it isn’t-well! he is a liar anyhow. I would

think it a bad job to have him stay in the house with so many valuables,

only that it will give me and my mate a chance of watching him. we’ll

keep a pretty good look-out, too, I tell you. He’s up in my room now,

guarding those lamps; but Johnny Wright is there too. I go on before he

comes off; so there won’t be much chance of another house-breaking. Of

course, Mr. Ross, all this, too, is between you and me.”

“Quite so! You may depend on my silence!” I said; and he went away to

keep a close eye on the Egyptologist.

It seemed as though all my painful experiences were to go in pairs, and

that the sequence of the previous day was to be repeated; for before

long I had another private visit from Doctor Winchester who had now paid

his nightly visit to his patient and was on his way home. He took the

seat which I proffered and began at once:

“This is a strange affair altogether. Miss Trelawny has just been

telling me about the stolen lamps, and of the finding of them in the

Napoleon cabinet. It would seem to be another complication of the

mystery; and yet, do you know, it is a relief to me. I have exhausted

all human and natural possibilities of the case, and am beginning to

fall back on superhuman and supernatural possibilities. Here are such

strange things that, if I am not going mad, I think we must have a

solution before long. I wonder if I might ask some questions and some

help from Mr. Corbeck, without making further complications and

embarrassing us. He seems to know an amazing amount regarding Egypt and

all relating to it. Perhaps he wouldn’t mind translating a little bit

of hieroglyphic. It is child’s play to him. What do you think?”

When I had thought the matter over a few seconds I spoke. We wanted all

the help we could get. For myself, I had perfect confidence in both

men; and any comparing notes, or mutual assistance, might bring good

results. Such could hardly bring evil.

“By all means I should ask him. He seems an extraordinarily learned man

in Egyptology; and he seems

Comments (0)