The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕

- Author: Bram Stoker

- Performer: -

Book online «The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕». Author Bram Stoker

would tempt him to depart from this resolution. The only concession he

would make was that he would find the ladders and bring them near the

cliff. This he did; and then, with the rest of the troop, he went back

to wait at the entrance of the valley.

“Mr. Trelawny and I took ropes and torches, and again ascended to the

tomb. It was evident that someone had been there in our absence, for

the stone slab which protected the entrance to the tomb was lying flat

inside, and a rope was dangling from the cliff summit. Within, there

was another rope hanging into the shaft of the Mummy Pit. We looked at

each other; but neither said a word. We fixed our own rope, and as

arranged Trelawny descended first, I following at once. It was not till

we stood together at the foot of the shaft that the thought flashed

across me that we might be in some sort of a trap; that someone might

descend the rope from the cliff, and by cutting the rope by which we had

lowered ourselves into the Pit, bury us there alive. The thought was

horrifying; but it was too late to do anything. I remained silent. We

both had torches, so that there was ample light as we passed through the

passage and entered the Chamber where the sarcophagus had stood. The

first thing noticeable was the emptiness of the place. Despite all its

magnificent adornment, the tomb was made a desolation by the absence of

the great sarcophagus, to hold which it was hewn in the rock; of the

chest with the alabaster jars; of the tables which had held the

implements and food for the use of the dead, and the ushaptiu figures.

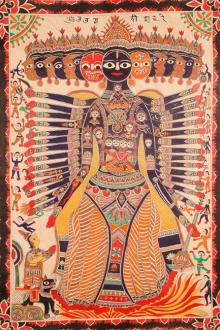

“It was made more infinitely desolate still by the shrouded figure of

the mummy of Queen Tera which lay on the floor where the great

sarcophagus had stood! Beside it lay, in the strange contorted

attitudes of violent death, three of the Arabs who had deserted from our

party. Their faces were black, and their hands and necks were smeared

with blood which had burst from mouth and nose and eyes.

“On the throat of each were the marks, now blackening, of a hand of

seven fingers.

“Trelawny and I drew close, and clutched each other in awe and fear as

we looked.

“For, most wonderful of all, across the breast of the mummied Queen lay

a hand of seven fingers, ivory white, the wrist only showing a scar like

a jagged red line, from which seemed to depend drops of blood.”

“When we recovered our amazement, which seemed to last unduly long, we

did not lose any time carrying the mummy through the passage, and

hoisting it up the Pit shaft. I went first, to receive it at the top.

As I looked down, I saw Mr. Trelawny lift the severed hand and put it in

his breast, manifestly to save it from being injured or lost. We left

the dead Arabs where they lay. With our ropes we lowered our precious

burden to the ground; and then took it to the entrance of the valley

where our escort was to wait. To our astonishment we found them on the

move. When we remonstrated with the Sheik, he answered that he had

fulfilled his contract to the letter; he had waited the three days as

arranged. I thought that he was lying to cover up his base intention of

deserting us; and I found when we compared notes that Trelawny had the

same suspicion. It was not till we arrived at Cairo that we found he

was correct. It was the 3rd of November 1884 when we entered the Mummy

Pit for the second time; we had reason to remember the date.

“We had lost three whole days of our reckoning—out of our lives—whilst

we had stood wondering in that chamber of the dead. Was it strange,

then, that we had a superstitious feeling with regard to the dead Queen

Tera and all belonging to her? Is it any wonder that it rests with us

now, with a bewildering sense of some power outside ourselves or our

comprehension? Will it be any wonder if it go down to the grave with us

at the appointed time? If, indeed, there be any graves for us who have

robbed the dead!” He was silent for quite a minute before he went on:

“We got to Cairo all right, and from there to Alexandria, where we were

to take ship by the Messagerie service to Marseilles, and go thence by

express to London. But

‘The best-laid schemes o’ mice and men Gang aft agley.’

At Alexandria, Trelawny found waiting a cable stating that Mrs. Trelawny

had died in giving birth to a daughter.

“Her stricken husband hurried off at once by the Orient Express; and I

had to bring the treasure alone to the desolate house. I got to London

all safe; there seemed to be some special good fortune to our journey.

When I got to this house, the funeral had long been over. The child had

been put out to nurse, and Mr. Trelawny had so far recovered from the

shock of his loss that he had set himself to take up again the broken

threads of his life and his work. That he had had a shock, and a bad

one, was apparent. The sudden grey in his black hair was proof enough

in itself; but in addition, the strong cast of his features had become

set and stern. Since he received that cable in the shipping office at

Alexandria I have never seen a happy smile on his face.

“Work is the best thing in such a case; and to his work he devoted

himself heart and soul. The strange tragedy of his loss and gain—for

the child was born after the mother’s death—took place during the time

that we stood in that trance in the Mummy Pit of Queen Tera. It seemed

to have become in some way associated with his Egyptian studies, and

more especially with the mysteries connected with the Queen. He told me

very little about his daughter; but that two forces struggled in his

mind regarding her was apparent. I could see that he loved, almost

idolised her. Yet he could never forget that her birth had cost her

mother’s life. Also, there was something whose existence seemed to

wring his father’s heart, though he would never tell me what it was.

Again, he once said in a moment of relaxation of his purpose of silence:

“‘She is unlike her mother; but in both feature and colour she has a

marvellous resemblance to the pictures of Queen Tera.’

“He said that he had sent her away to people who would care for her as

he could not; and that till she became a woman she should have all the

simple pleasures that a young girl might have, and that were best for

her. I would often have talked with him about her; but he would never

say much. Once he said to me: ‘There are reasons why I should not

speak more than is necessary. Some day you will know—and understand!’

I respected his reticence; and beyond asking after her on my return

after a journey, I have never spoken of her again. I had never seen her

till I did so in your presence.

“Well, when the treasures which we had—ah!—taken from the tomb had

been brought here, Mr. Trelawny arranged their disposition himself. The

mummy, all except the severed hand, he placed in the great ironstone

sarcophagus in the hall. This was wrought for the Theban High Priest

Uni, and is, as you may have remarked, all inscribed with wonderful

invocations to the old Gods of Egypt. The rest of the things from the

tomb he disposed about his own room, as you have seen. Amongst them he

placed, for special reasons of his own, the mummy hand. I think he

regards this as the most sacred of his possessions, with perhaps one

exception. That is the carven ruby which he calls the ‘Jewel of Seven

Stars’, which he keeps in that great safe which is locked and guarded by

various devices, as you know.

“I dare say you find this tedious; but I have had to explain it, so that

you should understand all up to the present. It was a long time after

my return with the mummy of Queen Tera when Mr. Trelawny re-opened the

subject with me. He had been several times to Egypt, sometimes with me

and sometimes alone; and I had been several trips, on my own account or

for him. But in all that time, nearly sixteen years, he never mentioned

the subject, unless when some pressing occasion suggested, if it did not

necessitate, a reference.

“One morning early he sent for me in a hurry; I was then studying in the

British Museum, and had rooms in Hart Street. When I came, he was all

on fire with excitement. I had not seen him in such a glow since before

the news of his wife’s death. He took me at once into his room. The

window blinds were down and the shutters closed; not a ray of daylight

came in. The ordinary lights in the room were not lit, but there were a

lot of powerful electric lamps, fifty candle-power at least, arranged on

one side of the room. The little bloodstone table on which the

heptagonal coffer stands was drawn to the centre of the room. The

coffer looked exquisite in the glare of light which shone on it. It

actually seemed to glow as if lit in some way from within.

“‘What do you think of it?’ he asked.

“‘It is like a jewel,’ I answered. ‘You may well call it the

‘sorcerer’s Magic Coffer”, if it often looks like that. It almost seems

to be alive.’

“‘Do you know why it seems so?’

“‘From the glare of the light, I suppose?’

“‘Light of course,’ he answered, ‘but it is rather the disposition of

light.’ As he spoke he turned up the ordinary lights of the room and

switched off the special ones. The effect on the stone box was

surprising; in a second it lost all its glowing effect. It was still a

very beautiful stone, as always; but it was stone and no more.

“‘Do you notice anything about the arrangement of the lamps?’ he asked.

“‘No!’

“‘They were in the shape of the stars in the Plough, as the stars are in

the ruby!’ The statement came to me with a certain sense of conviction.

I do not know why, except that there had been so many mysterious

associations with the mummy and all belonging to it that any new one

seemed enlightening. I listened as Trelawny went on to explain:

“‘For sixteen years I have never ceased to think of that adventure, or

to try to find a clue to the mysteries which came before us; but never

until last night did I seem to find a solution. I think I must have

dreamed of it, for I woke all on fire about it. I jumped out of bed

with a determination of doing something, before I quite knew what it was

that I wished to do. Then, all at once, the purpose was clear before

me. There were allusions in the writing on the walls of the tomb to the

seven stars of the Great Bear that go to make up the Plough; and the

North was again and again emphasized. The same symbols were repeated

with regard to the

Comments (0)