The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕

- Author: Bram Stoker

- Performer: -

Book online «The Jewel of Seven Stars by Bram Stoker (books to read in your 20s TXT) 📕». Author Bram Stoker

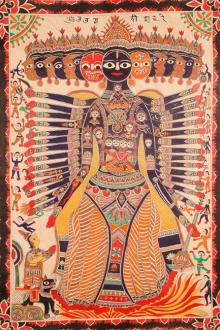

“Queen Tera was ruled in great degree by mysticism, and there are so

many evidences that she looked for resurrection that naturally she would

choose a period ruled over by a God specialised to such a purpose. Now,

the fourth month of the season of Inundation was ruled by Harmachis,

this being the name for ‘Ra’, the Sun-God, at his rising in the morning,

and therefore typifying the awakening or arising. This arising is

manifestly to physical life, since it is of the mid-world of human daily

life. Now as this month begins on our 25th July, the seventh day would

be July 31st, for you may be sure that the mystic Queen would not have

chosen any day but the seventh or some power of seven.

“I dare say that some of you have womdered why our preparations have

been so deliberately undertaken. This is why! We must be ready in

every possible way when the time comes; but there was no use in having

to wait round for a needless number of days.”

And so we waited only for the 31st of July, the next day but one, when

the Great Experiment would be made.

We learn of great things by little experiences. The history of ages is

but an indefinite repetition of the history of hours. The record of a

soul is but a multiple of the story of a moment. The Recording Angel

writes in the Great Book in no rainbow tints; his pen is dipped in no

colours but light and darkness. For the eye of infinite wisdom there is

no need of shading. All things, all thoughts, all emotions, all

experiences, all doubts and hopes and fears, all intentions, all wishes

seen down to the lower strata of their concrete and multitudinous

elements, are finally resolved into direct opposites.

Did any human being wish for the epitome of a life wherein were gathered

and grouped all the experiences that a child of Adam could have, the

history, fully and frankly written, of my own mind during the next

forty-eight hours would afford him all that could be wanted. And the

Recorder could have wrought as usual in sunlight and shadow, which may

be taken to represent the final expressions of Heaven and Hell. For in

the highest Heaven is Faith; and Doubt hangs over the yawning blackness

of Hell.

There were of course times of sunshine in those two days; moments when,

in the realisation of Margaret’s sweetness and her love for me, all

doubts were dissipated like morning mist before the sun. But the

balance of the time-and an overwhelming balance it was-gloom hung over

me like a pall. The hour, in whose coming I had acquiesced, was

approaching so quickly and was already so near that the sense of

finality was bearing upon me! The issue was perhaps life or death to

any of us; but for this we were all prepared. Margaret and I were one

as to the risk. The question of the moral aspect of the case, which

involved the religious belief in which I had been reared, was not one to

trouble me; for the issues, and the causes that lay behind them, were

not within my power even to comprehend. The doubt of the success of the

Great Experiment was such a doubt as exists in all enterprises which

have great possibilities. To me, whose life was passed in a series of

intellectual struggles, this form of doubt was a stimulus, rather than

deterrent. What then was it that made for me a trouble, which became an

anguish when my thoughts dwelt long on it?

I was beginning to doubt Margaret!

What it was that I doubted I knew not. It was not her love, or her

honour, or her truth, or her kindness, or her zeal. What then was it?

It was herself!

Margaret was changing! At times during the past few days I had hardly

known her as the same girl whom I had met at the picnic, and whose

vigils I had shared in the sick-room of her father. Then, even in her

moments of greatest sorrow or fright or anxiety, she was all life and

thought and keenness. Now she was generally distraite, and at times in

a sort of negative condition as though her mind—her very being—was not

present. At such moments she would have full possession of observation

and memory. She would know and remember all that was going on, and had

gone on around her; but her coming back to her old self had to me

something the sensation of a new person coming into the room. Up to the

time of leaving London I had been content whenever she was present. I

had over me that delicious sense of security which comes with the

consciousness that love is mutual. But now doubt had taken its place.

I never knew whether the personality present was my Margaret—the old

Margaret whom I had loved at the first glance—or the other new Margaret,

whom I hardly understood, and whose intellectual aloofness made an

impalpable barrier between us. Sometimes she would become, as it were,

awake all at once. At such times, though she would say to me sweet and

pleasant things which she had often said before, she would seem most

unlike herself. It was almost as if she was speaking parrot-like or at

dictation of one who could read words or acts, but not thoughts. After

one or two experiences of this kind, my own doubting began to make a

barrier; for I could not speak with the ease and freedom which were

usual to me. And so hour by hour we drifted apart. Were it not for the

few odd moments when the old Margaret was back with me full of her charm

I do not know what would have happened. As it was, each such moment

gave me a fresh start and kept my love from changing.

I would have given the world for a confidant; but this was impossible.

How could I speak a doubt of Margaret to anyone, even her father! How

could I speak a doubt to Margaret, when Margaret herself was the theme!

I could only endure—and hope. And of the two the endurance was the

lesser pain.

I think that Margaret must have at times felt that there was some cloud

between us, for towards the end of the first day she began to shun me a

little; or perhaps it was that she had become more diffident that usual

about me. Hitherto she had sought every opportunity of being with me,

just as I had tried to be with her; so that now any avoidance, one of

the other, made a new pain to us both.

On this day the household seemed very still. Each one of us was about

his own work, or occupied with his own thoughts. We only met at meal

times; and then, though we talked, all seemed more or less preoccupied.

There was not in the house even the stir of the routine of service. The

precaution of Mr. Trelawny in having three rooms prepared for each of us

had rendered servants unnecessary. The dining-room was solidly prepared

with cooked provisions for several days. Towards evening I went out by

myself for a stroll. I had looked for Margaret to ask her to come with

me; but when I found her, she was in one of her apathetic moods, and the

charm of her presence seemed lost to me. Angry with myself, but unable

to quell my own spirit of discontent, I went out alone over the rocky

headland.

On the cliff, with the wide expanse of wonderful sea before me, and no

sound but the dash of waves below and the harsh screams of the seagulls

above, my thoughts ran free. Do what I would, they returned

continuously to one subject, the solving of the doubt that was upon me.

Here in the solitude, amid the wide circle of Nature’s foce and strife,

my mind began to work truly. Unconsciously I found myself asking a

question which I would not allow myself to answer. At last the

persistence of a mind working truly prevailed; I found myself face to

face with my doubt. The habit of my life began to assert itself, and I

analysed the evidence before me.

It was so startling that I had to force myself into obedience to logical

effort. My starting-place was this: Margaret was changed—in what way,

and by what means? Was it her character, or her mind, or her nature? for

her physical appearance remained the same. I began to group all that I

had ever heard of her, beginning at her birth.

It was strange at the very first. She had been, according to Corbeck’s

statement, born of a dead mother during the time that her father and his

friend were in a trance in the tomb at Aswan. That trance was

presumably effected by a woman; a woman mummied, yet preserving as we

had every reason to believe from after experience, an astral body

subject to a free will and an active intelligence. With that astral

body, space ceased to exist. The vast distance between London and Aswan

became as naught; and whatever power of necromancy the Sorceress had

might have been exercised over the dead mother, and possibly the dead

child.

The dead child! Was it possible that the child was dead and was made

alive again? Whence then came the animating spirit—the soul? Logic was

pointing the way to me now with a vengeance!

If the Egyptian belief was true for Egyptians, then the “Ka” of the dead

Queen and her “Khu” could animate what she might choose. In such case

Margaret would not be an individual at all, but simply a phase of Queen

Tera herself; an astral body obedient to her will!

Here I revolted against logic. Every fibre of my being resented such a

conclusion. How could I believe that there was no Margaret at all; but

just an animated image, used by the Double of a woman of forty centuries

ago to its own ends … ! Somehow, the outlook was brighter to me now,

despite the new doubts.

At least I had Margaret!

Back swung the logical pendulum again. The child then was not dead. If

so, had the Sorceress had anything to do with her birth at all? It was

evident—so I took it again from Corbeck—that there was a strange

likeness between Margaret and the pictures of Queen Tera. How could

this be? It could not be any birth-mark reproducing what had been in

the mother’s mind; for Mrs. Trelawny had never seen the pictures. Nay,

even her father had not seen them till he had found his way into the

tomb only a few days before her birth. This phase I could not get rid

of so easily as the last; the fibres of my being remained quiet. There

remained to me the horror of doubt. And even then, so strange is the

mind of man, Doubt itself took a concrete image; a vast and impenetrable

gloom, through which flickered irregularly and spasmodically tiny points

of evanescent light, which seemed to quicken the darkness into a

positive existence.

The remaining possibility of relations between Margaret and the mummied

Queen was, that in some occult way the Sorceress had power to change

places with the other. This view of things could not be so lightly

thrown aside. There were too many suspicious circumstances to warrant

this, now that my attention was fixed on it and my intelligence

recognised the possibility. Hereupon there began to come into my mind

all the strange incomprehensible matters which had whirled through our

lives in

Comments (0)