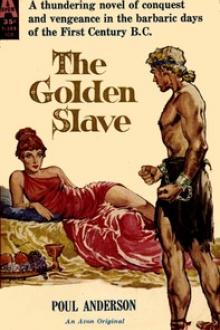

The Golden Slave by Poul William Anderson (beach read book txt) 📕

- Author: Poul William Anderson

- Performer: -

Book online «The Golden Slave by Poul William Anderson (beach read book txt) 📕». Author Poul William Anderson

"I think it amused the redbeard to have me wait on you," he said. His mouth quirked. "He has not heard that Rome has festivals every year wherein the Roman serves his own household slaves."

"But I am no more a slave!" said Phryne, as much to herself as to him. She had seen little of this man; she was bought in his absence and served his wife, whom he avoided. But he was a master, and no decent person would—But I have gone beyond decency, she thought; beyond civilization, at least. I am outlaw not only in Rome but in Rome's mother Hellas.

The knowledge was a desolation.

Flavius poured the water into a tub screwed to the floor. It slapped about with the rocking of the ship. He glanced at her, sideways. Finally he said, with a tone of smothered merriment, in flawless Greek: "My dear, you will always be a slave. Do you think because that white skin was never branded your soul escaped?"

"My fathers were free men in their own city when yours were Etruscan vassals!" she cried, stamping her foot in anger.

Flavius shrugged. "Indeed. But we are neither of us our fathers." His voice became deep, and he regarded her levelly. "I say to you, though, the slave-brand is on you. It was burned in with ... fair words on fine parchment; white columns against a summer sky; a bronze-beaked ship seen over blue waters; grave men with clean bodies and Plato on their tongues; a marching legion, where a thousand boots smite the earth as one; a lyre and a song, a jest and a kiss, among blowing roses. Oh, if the gods I do not believe in are cruel enough to grant your wish, you could give your body to some North-dweller—you could learn his hog-language and pick the lice from his hair and bear him another squalling brat every year, till they bury you toothless at forty years of age in a peat bog where it always rains. That could happen. But your soul would forever be chained by the Midworld Sea."

She said, shaking, "If you twist words about thus, then you, too, are a slave."

"Of course," he said quietly. "There are no free and unfree; we are all whirled on our way like dead leaves, from an unlikely beginning to a ludicrous end. I do not speak to you now, the sounds that come from my mouth are made by chance, flickering within the bounds of causation and natural law. Truly, we are all slaves. The sole difference lies between the noble and the ignoble."

He folded his arms and leaned back against the jamb. "What you have done proves you are of the noble," he said. "I would manumit you if we came back to Rome—give the Senate some perjured story, if need be, to save you from the law. I would give you money and a house of your own in Greece."

"Are you trying to bribe me?" she flared.

"Perhaps. But that comes later. What I have just offered is a free gift, whether you stand by the Cimbrian or not, provided only of course that we both get back to Rome somehow. It will be a thing I do of my own accord, because we are the same kind, you and I, and it is a cursedly lonely breed of animal."

His grin flashed. "Now, to be sure, if you would like to help assure—"

She drew her knife. "Get out!" she screamed.

Flavius raised his brows, but left. Phryne slammed the door after him. A while she smote her hands together. Then, viciously, she tore off her tunic and washed herself.

Wrapped in the mantle, she emerged again. She felt calmer—on the surface; underneath was a dark clamor in an unknown language. Sundown blazed among restless clouds; the mast swayed back and forth in heaven. Tjorr sat on a barrel under the forecastle, drumming his heels as he raised a stolen chalice. Elsewhere men crowded shrieking about lashed casks, and the deck that had been bloodied was now stained purple. Phryne shivered and drew the wool closer about her. This was going to be a night where Circe reigned.

She looked aft. A small cluster of men stood together around Flavius' tall form. She recognized Demetrios, the youth Quintus, two or three others. Briefly, she was afraid. But—a few unarmed malcontents? she asked herself scornfully.

She walked forward. A locked hatch cover muffled some weird noises—what was that? Oh, to be sure, the free crew and the more timid slaves of this galley had been chained to the rowers' benches down there.

Tjorr boomed at her, "Hoy, shield maiden! Come drink with me! You've earned it!"

Phryne joined him. One man snatched after her. Tjorr tossed his hammer, casually. The man screamed and hopped about, clutching his bare toes. "Next one insults my girl gets it in the brisket," said Tjorr without rancor. "Now bring me back that maul."

Phryne accepted the cup he sloshed into the barrel for her. She held it two-handed, bracing herself against the ship's long swinging. Barbarous to drink it undiluted, she thought; but fresh water was too begrudged at sea. She looked at the hairy, squatting shapes that ringed her in and asked, "Will there not be fights that disable men we need?"

Tjorr pointed to a chest behind the barrel. "All arms save our own are in there," he said. "And here I'll sit all night. I'm not unaware of that Flavius cockroach, little one. Were I the chief, he'd have been fish food long ago."

"Is your life so much more to you than your honor?" she bridled.

"Well, I suppose not. But I've three small sons at home. The youngest was just starting to walk on his little bandy legs when I went off. And then there's my woman, too, if she's not wed another by now, and—Well, anyhow, it would be bitter to die without drinking of the Don again." Tjorr tossed off his cup and dipped it in once more.

"Where would you yourself go?" he asked.

Phryne stared eastward, where night came striding into the wind. "I do not know," she said.

"Hm? But surely—you spoke of Egypt—"

"It may be. Perhaps in Alexandria.... Leave me alone!" Phryne went from him, up the ladder and into the bow.

She huddled there a long time. No one ventured past Tjorr; she could be by herself. Down on the main deck the scene grew more wild and noisy each hour; by torch and hearth-light she glimpsed revels as though Pan the terrible had put to sea. One small corner of civilization remained, far aft below the poop, where Flavius and his comrades warmed their hands over a brazier and drank so slowly she was not certain they drank at all.

The moon seemed to fly through heaven, pale among great driving clouds. It showed fleetingly how the waters surged from the west—not very high as yet, but with foam on black waves. And the wind droned louder than before.

Phryne sat under the bulwarks and nursed her beaker, letting the wine warm her only a little. This was no time to flee her trouble. She must choose a road.

And what was there for her?

Briefly, when they had planned where to go on their newly won ship, it had flamed up—perhaps Antinous was in Alexandria, perhaps she could find him again! Too long had he kissed her only in dreams. She hearkened back to the last time when she awoke crying his name.... She knew, then, suddenly, that she had not really seen his face in the dream. She had not done so for months. She could not even call it to mind now—it was a blur; he had had a straight nose and gray eyes and so on, but she only remembered the words.

Well, Time devoured all things at last, but it might have spared the ghost she bore of Antinous.

Nevertheless, she thought, she could stay in Alexandria.... No, what hope had a woman without friends? There were only the brothels; better to seek the sea's decency this very night. She could follow Eodan toward his barbarian goal, most likely to his death along the way, but suppose they did get back to this Cimberland, what then? Eodan would house her, but she would not be a useless leech on any man. And so she would merely exist, alone on the marches of the world, until finally in her need she let some brainless red youth tumble her in his hut.

She wondered drearily if Flavius had meant his offer. It was the best of an evil bargain. And if he lied—well, then she would die, and the shades did not remember this earth.

When Eodan released Flavius, she would go with him to Rome.

The decision brought peace, after so many hours of treading the same round like a blinded ox grinding wheat. Perhaps now she could sleep. It was very late. The revelry had ended. By the light of a sinking moon, glimpsed through clouds, she saw men sprawled across the deck, their cups and their bodies rolling with the ship. A few feeble voices hiccoughed some last song, but, mostly, they were all snoring to match the wind. Phryne stood up, stiff-limbed, to seek her tent on the smaller galley.

The brazier under the poop was still aglow. A dark figure crossed in front of it, and another and another. Flavius' party was retiring, too. Being sober, they would have the sense to go below to sleep. One of them had just entered the poop....

No, what was it he came back with? Torchlight shimmered on iron. A crowbar from the carpenter's kit? And there were hammers, a drawknife, even a saw. O father Zeus, weapons!

Flavius led them across the deck. The last half-dozen celebrants, seated in a ring about a wine cask, looked up. "Well," Phryne heard, "who 'at? c'mere, old frien', c'mere f' little drink—"

Flavius struck coldly with his bar. Two hammers beat as one, thock, thock—like butchers, the three men stunned those who sat. Quintus cackled gleefully and began to saw a throat across. "No need!" snapped Flavius. "This way!"

Phryne threw herself to the planks. What if they had seen her? Her heart beat so wildly she feared it would burst. As though from immensely far off, she heard Flavius break the lock on the hatch and go below.

Phryne caught her lip in her teeth to hold it steady. She could just see one man standing guard on deck while the others were breaking off chains in the rowers' pit. Could he see her in turn, if she—but if she lay still, he would find her at sunrise!

Phryne inched to the ladder. Down, now. Moonlight fell on Tjorr, sprawled back against the weapon chest. His mouth was open and he was making private thunder in his nose. Phryne crouched beside him. He was too massive; her hands would not shake him enough. "Tjorr! Tjorr, it is mutiny!" she whispered. "Tjorr, wake up!"

"What's that?" A ragged, half-frightened cry from the guard. Phryne saw him against the sky, peering about.

"Uh," mumbled Tjorr. He swatted at her and rolled over.

Phryne drew her knife. The guard shaded his eyes, staring forward. "Is somebody awake there?" he called.

She put her mouth to the Alan's ear. "Wake, wake," she whispered. "You sleep yourself into Hades."

A man's head rose over the hatch coaming. "Somebody's astir up there," chattered the sentry.

"We'll go see," said the man. His burst-off chains swung from his wrists; it was the last mutiny all over again. How the gods must be laughing! Another followed him. Phryne recognized Quintus' ferret body.

"Ummmm," said Tjorr and resumed his snoring.

Phryne put her dagger point on a buttock and pushed.

"Draush-ni-tchaka-belog!" The Sarmatian came to his feet with a howl. "What muck-swilling misbegotten son of—Oh!" His gaze wobbled to rest on the man running toward him. The hammer seemed to leap into his hand.

"Up!" he bawled. "Up and fight!"

Phryne dashed past him. Eodan still slept, she thought wildly; they could fall upon him unawares

Comments (0)