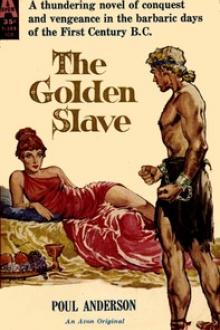

The Golden Slave by Poul William Anderson (beach read book txt) 📕

- Author: Poul William Anderson

- Performer: -

Book online «The Golden Slave by Poul William Anderson (beach read book txt) 📕». Author Poul William Anderson

"Enough." Mithradates turned to Phryne. "Well, girl, what is it you wished so badly to say to me?"

She might have fallen at his feet; but she stood before him like a visiting queen. Her tones fell soft: "Great King, I would do no more than plead for the lives of two brave men. My own does not matter."

"For that," said Mithradates, "I shall surely never let you go."

Flavius said with a devouring bitterness: "Your Majesty, the Senate of Rome does not feel this female slave is of great importance, nor even the Alanic barbarian. It is not recommended to Your Majesty that you leave them alive, but I feel the King will soon discover that for himself. However, the Cimbrian, ringleader and evil genius of them all, must be done away with. We would prefer he die in Rome, but otherwise he must die here. I have already presented Your Majesty with the written consular decree of the Republic. May I say to the Great King, in the friendliest spirit, knowing that a word to the wise is sufficient—should I return with this decree unfulfilled, the Senate may be forced to reckon it a cause for war."

XVII"You bid me surrender a guest, who has fought well for me to boot," Mithradates said gravely. And then, with an imp's grin: "Also, I doubt the reality of your threat. If the Cimbri were all like this one, Europe must still be too shaken to go adventuring in the East. Ten years hence, perhaps ... but no one would hazard so rich a province as Pergamum just to capture a man. I have read your official documents, Flavius, and they convey nothing but a strong request."

"Great King, it was never my intention to threaten," answered the Roman with a smooth quickness. "Forgive clumsy words. We are blunt folk in the Republic. But of course the King understands that the Senate and the people of Rome will welcome so vital a token of a most powerful and splendid monarch's good will toward them. I am authorized to make a small material symbol of the state's gratitude, to the amount of—"

"I have seen what the bribe would be," said Mithradates. "We shall discuss all this at leisure tonight." His gaze flickering between Eodan and Flavius, he chuckled deeply. "There will be a feast at which you two old friends may reminisce. In the meantime, I forbid violence between you. Now I have work to do. You may go."

Eodan backed out, taking Phryne's arm at the door. "Come to my tent," he said. "You should not have been so reckless as to travel hither."

"I would not hold back from you even the littlest help," she whispered. She caught at his cloak, and her tone became shrill. "Eodan, will he give you up to them?"

"I hardly think so," said the Cimbrian. Bitterness swelled in his throat. "But neither will he give Flavius up to me!"

They started across the courtyard, and the wind snatched at their mantles. Eodan looked back and saw Flavius emerging from the keep.

"Wait," he said to Phryne. "There are things I would talk about that no one else has a right to hear."

"You will disappoint the king," she said in an acrid voice. "He is looking forward to the subtlest gladiatorial contest."

Eodan strode from her. Flavius wrapped his toga more closely against the cold bluster of the air. He smiled, raising his brows, and stood waiting; his dark curly hair fluttered. But somehow no youth or merriment were left in him.

"Will you be kind enough to assault me?" he asked.

"I am not a fool," grunted Eodan.

"No, not in such respects.... Since your life hangs now on the king's pleasure, you will heel to his lightest whim like any well-trained dog." Flavius spoke quietly, choosing each word beforehand. "Thus it is seen—he who is born to be a slave will always be a slave."

Eodan held onto his soul with both hands. At last he got out: "I will meet you somewhere beyond the power of both Rome and Pontus."

Flavius skinned his teeth in a grin. "Your destruction is more important to me than the dubious pleasures of single combat."

"You are afraid, then," said Eodan. "You only fight women."

Flavius clenched his free hand. His whittled face congealed, he said in a flat voice: "I cannot help but smite those women whom you forever make your shields. Now it is a Greek slave girl. How many more have you crawled behind, even before you debauched my wife?"

"I went through a door that stood unbarred to all," fleered Eodan.

"Like unto like. Will it console you to know, Cimbrian, that she has divorced me? For she grows great with no child of mine, a brat I would surely drown were it dropped in my house."

Eodan felt a dull pleasure. This was no decent way to hurt an enemy, yet what other way did he have? "So now your hopes for the consulate are broken," he said. "That much service have I done Rome."

"Not so," Flavius told him. "For I allowed the divorce in an amicable way, not raising the charges of adultery I might. Thus her father is grateful to me." He nodded. "There are troublous years coming. The plebs riot and the patricians fall out with each other. I shall rise high enough in the confusion so that I will have power to proscribe your bastard."

It had never occurred to Eodan before, to think about the by-blow of his women. He had set Hwicca's Othrik upon his knee and named him heir, but otherwise—Now, far down under the seething in him, he knew a tenderness. He could find no good reason for it; there was a Power here. He would have chanced Mithradates' wrath and broken the neck of Flavius, merely to save an unborn child, little and lonely in the dark, whom he would never see. But no, those guardsmen drilling beneath the walls would seize him before he finished the task.

He asked in a sort of wonder: "Is this why you pursue me?"

"I bear the commission of the Republic."

"The king spoke truly—they are not that interested in one man. This decree is a gesture to please you, belike through your father-in-law. You are the one who has made it his life's work to destroy me."

"Well, then, if you wish, I am revenging Cordelia," said Flavius. His eyes shifted with a curious unease.

"I spared you at Arausio. And what was Cordelia to you, ever?"

"So now you call up the past and whine for your life."

"Oh, no," said Eodan softly. "I thank all the high gods that we meet again. For you killed my Hwicca."

"I did?" cried Flavius. His skin was chalky. "Now the gods would shatter you, did they exist!"

"Your sword struck her down," said Eodan.

"After you flung her upon it!" shrieked Flavius. "You are her murderer and none but you! I have heard enough of your filth!"

He whirled and almost ran. Phryne, small and solitary at the gate, flinched aside from him. He vanished.

Eodan stood for a while staring after the Roman. It came to him finally, like a voice from elsewhere: So that is why he must hate me. He also loved Hwicca, in his own way. Indeed the soul of man is a forest at night.

He thought coldly, It is well. Now I can be certain that Flavius will never depart my track until one of us has died.

Phryne joined him as he left. As they went mutely from the castle, Tjorr rushed up to them. "There are Romans come!" he bawled. "A dozen Roman soldiers in camp.... I'd swear I saw Flavius himself go by.... Phryne! You are here!"

"Have you any further information?" asked the girl sweetly.

They walked toward Eodan's tent, and she explained to the Alan what had happened. Tjorr gripped his hammer. "By the thunder," he said, "it was well done of you! But what help did you think you could give us?"

"I did not know," she answered unsteadily, "nor am I certain yet. A word, perhaps ... one more voice to plead, with a flattering abasement impossible to Eodan ... or some scheme—I could not stay away."

Tjorr looked at the Cimbrian's unheeding back. "Be not angry with him if he shows you cold thanks," he said. "There has been a blackness in him of late, and this cannot have lightened it."

"He has already rewarded me beyond measure," she said, "by the way he greeted me."

They entered the tent. Eodan slumped on a heap of skins and wrapped solitude about himself. After some low-voiced talk with Phryne, it occurred to Tjorr to take her out and show her to his and Eodan's personal guards, grooms and other attendants. "She is not to be insulted. Obey her as you would obey me. Any who behaves otherwise, I'll break his head. D'you hear?"

When they came back it was approaching sunset. Eodan was sitting before a small pile of silks, linens and ornaments. "A slave brought these for you, Phryne," he said. "The king commands your presence at his feast."

"The king!" She stared bewildered. "What would the king with me?"

"Be not afraid," said Eodan. "He is only cruel to his enemies."

Tjorr's eyes glittered. "But this is wonderful!" he cried. "Girl, your fortune may be made! I'll get a female to help you dress—"

When she had gone he muttered, "She did not appear overly glad of the king's favor."

"She is too frightened on our behalf," said Eodan.

"Do you think she has good reason to fear?"

"I do not know—nor care, if I can only lay hands on Flavius."

As twilight fell, an escort of torchbearers came to bring them to the castle. Entering the feasting hall, Eodan saw it aglow with lamps. Some attempt to make it worthy of the king was shown by plundered robes strewn on the floor; musicians stood in the murk under the god-pillars and caterwauled. It was no large banquet Mithradates gave this night—couches for a score of his officers, with Eodan on his right and Tjorr beyond him, Flavius on the left. Cimbrian and Alan wore Persian dress, to defy the plain white tunic of the Roman. The rest clad their Anatolian bodies in Greek style, save that the king had thrown a purple robe over his wide shoulders.

Eodan greeted Mithradates and the nobles as always, and reclined himself stiffly. The king helped himself to fruit from a crystal bowl. "Never before has this place known such an assembly of the great," he declared with sardonic sententiousness. "And yet our chief guest has not been summoned."

"Who might that be, Lord of the World?" asked a Pontine.

"It is not our custom that women dine with men," said Mithradates. "We feel it a corruption of older and manlier ways." That was a malicious dart at Flavius, thought Eodan. "Yet all you nobles would consider it no insult to guest a queen; and many philosophers assure us that royalty is a matter of the spirit rather than of birth."

"Though the Great King shows that when spirit and birth unite, royalty comes near godhood," said an officer with practiced readiness.

"I am therefore pleased to present to you all a veritable Atalanta—or an Amazon princess—or even an Athena, wise as well as valiant. Let Phryne of Hellas stand forth!"

She walked from the inner door, urged by a chamberlain. Her garb was dazzling—long lustrous gown and flowing silken mantle, her hair and throat and arms a barbaric blaze of finery. It came as a wrenching in Eodan that she should look so unhappy. She advanced with downcast eyes and prostrated herself.

"No—up, up!" boomed Mithradates. "The King would have you share his place."

Eodan heard a muffled snicker at the table's end. Blood beat thickly in his temples; what right had some Asiatic to laugh at a Greek? His eyes ranged in search of the man, to deal with him later. By the time he looked back, Phryne had reclined beside Mithradates on the royal couch.

"Know," said the ruler in his customary

Comments (0)