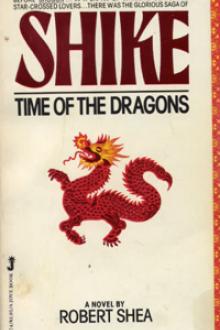

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

“Your son, Takashi no Atsue, is gone from this world,” Hideyori said quietly. “You must accept it and go on.” Atsue’s full name, which Taniko herself never spoke aloud, sounded like that of a stranger on the Muratomo chieftain’s lips. It brought home to her again the reality of what had happened. Atsue was dead. Killed by some Muratomo samurai. She could no longer contain her grief. A long scream tore itself from the very core of her body, and she burst into a storm of weeping. She bent double over the sword and flute, convulsed by sobs. Hideyori sat silently, his face averted.

At last her anguish subsided enough for her to speak. “Eorgive me.”

“There is nothing to forgive. You have suffered greatly.”

Taniko’s mind went back to that terrible time in Heian Kyo when no one dared tell her Kiyosi was dead until Sogamori’s secretary blurted it out. “I am grateful to you, Lord Hideyori,” she said formally. “You had no duty to tell me of the death of one of your enemies. You were under no obligation to spend so much of your precious time with me to comfort me in my grief. I am obliged to you for taking this task upon yourself.”

“It might have been much more difficult for me,” said Hideyori, his glance darting sideways at her. “I am grateful that you did not ask me how he died.”

“What do you mean?”

Hideyori looked perturbed. “I meant nothing.”

“You have not told me everything.”

“No, no. I have said enough already.”

“I want to know all, Hideyori-san. Do not leave some ugly truth lying in wait to catch me unaware later on. Let me suffer now all that I must suffer.”

“Please, Tanikosan, do not ask me to say any more. You will regret it.”

“Did he die dishonourably? Did he commit some act of cowardice?” “No, it was not that, Taniko. Will you force me to tell you, then?” “Please speak.”

Hideyori sighed. “This sword and this flute were sent to me as spoils of war by my half-brother, Yukio. It was Yukio who killed your son.” Taniko bit her lip. “No.” Not Yukio. It would not be. Not Jebu’s dearest friend. Not the smiling companion who had helped her return from China to the Sacred Islands. She felt as if she were falling into an abyss without light and without bottom.

Hideyori went on. “Atsue was captured during the battle at Ichinotani by the giant Zinja monk Jebu, who travels with Yukio. The Zinja brought Atsue to Yukio. When Yukio learned that Atsue was Sogamori’s grandson, he instantly cut off the defenceless boy’s head.”

“Sogamori’s grandson? But Yukio and Jebu both knew that Atsue was my son:” Taniko felt her body grow cold.

“Apparently that did not affect Yukio’s angry mood,” said Hideyori. “It is well known that he has a furious temper.”

“Homage to Amida Buddha,” Taniko whispered, but the Lord of Boundless Light was far from her lightless chasm. “Was there a letter?” she asked, after a long silence in which she fought to overcome the pain.

“No. The samurai who brought the sword and the flute told me how your son died.”

“If Yukio sent these things, he must have regretted killing Atsue.”

“He sent them to me because they are Takashi treasures. Knowing I distrust him, he seeks to curry favour with me. I felt that I should give them to you.”

“Did the monk Jebu try to stop Yukio from killing my son?” “If he did, I did not hear of it.”

“I would like to speak to the samurai who brought the sword and the flute.”

“I’m sorry, but he has already gone back to rejoin Yukio’s army.”

Taniko rose to her feet, clutching the sword and the flute to her breast. “Eorgive me, my lord, but I must ask your permission to leave. I must be alone.”

“Kwannon bring comfort to you, Tanikosan.”

Knowing that everyone in the palace was constantly watched on Hideyori’s orders, Taniko decided to ride out into the hills. There she would defy her karma. She would kill herself. Of course, she would be reborn to suffer more, but at least the bitter memories of this life, in which she had been so cruelly betrayed by those she trusted and loved, would be wiped away. She considered leaving a final farewell message in her pillow book, but there was no longer anyone she wanted to write to. That in itself, she thought, is a good reason to leave this world.

Soon her horse was climbing the hills along the same road she and Jebu had followed twenty-two years earlier on their first journey together. The houses of Kamakura had spread into those hills, and it took her much longer to reach the thick pine woods. The path wound to a spot from which she was able to see the whole sweep of forest, city and ocean. The blackness all around was dotted by countless tiny points of illumination, the fireflies in the trees, the lanterns in the streets and gardens below, the phosphorescence on the rolling surface of the ocean, the blazing stars overhead. The beauty of this moonless night penetrated the numbness of her grief. She decided she would follow the forest path to the top of this hill. There she would sit under a pine with Kogarasu and Little Branch in her lap. She would take out the small dagger concealed in her kimono, and when she felt ready, perhaps at sunrise, she would cut her throat and let her blood spill over these last things she had from Atsue.

She felt a momentary surge of annoyance when her horse neared the top of the hill and she saw it was already occupied by a little temple, scarcely larger than a hut, with a thatched roof. The doorway of the small building faced east, hiding its light from any traveller approaching from the city. She had never heard of a temple on this hill, but as Kamakura grew in importance the forests around it were filling up with yamabushi, mountain-dwelling monks. Perhaps she was meant to find this temple. By saying “Homage to Amida Buddha,” with perfect faith one might achieve rebirth in Amida’s Western Paradise where it was possible-as it was not in this corrupt world-for an ordinary person to attain Nirvana. Taniko had been invoking the Buddha for most of her life, but she had no way of knowing whether any of her prayers had enough purity to release her from the anguish of being reborn on this earth. Perhaps in one last visit to a temple she might find the wings of grace that would carry her to Amida’s paradise.

The temple was very small and utterly bare, like Hideyori’s prayer chamber. There was not even a statue of a Buddha or bosatsu on the altar, where a small oil lamp provided the only illumination. Taniko walked to the altar, bowed and clapped her hands to get the attention of whatever deity might dwell in this temple. Aloud she said, “Homage to Amida Buddha.”

“A waste of breath,” said a voice behind her.

The irreverent remark immediately made Taniko think robbers must have taken over the temple. She whirled, preparing to defend her honour or kill herself here and now, if necessary, with her dagger. In the shadows on one side of the room a black-robed monk sat in the lotus position, smiling at her. He had been so silent and immobile when she entered that she hadn’t noticed him. She bowed in reverence to his vows, though his words were odd for a monk.

“Why wasted breath, sensei?”

The monk had a round, cheerful face and a chunky body. Though he was utterly motionless, there was such a strength in his sitting that it seemed not even elephants would be able to budge him. His eyes penetrated Taniko’s mind, giving her the feeling that he knew her because he knew the whole universe, and that he contained the universe in himself.

“Amida Buddha does not exist,” he said.

“What? Amida does not exist? What teachings do you profess, monk?”

“I teach nothing special. What sort of teaching are you looking for?” In spite of his odd words there was a kindness in his face that made her like and trust him. She needed to believe in someone. It was because she could no longer believe in anyone that she wanted to die.

“I’m not looking for teaching. I want peace, nothing else.” In a rush, she poured out her story. By the time she had finished telling the stocky monk about Kiyosi, Atsue, Yukio and Jebu, the two of them were seated facing each other before the empty altar. Though she’d had to pause several times to release the tears that seemed to fill up her whole body, the telling had eased her grief. Even so, as she admitted to the monk, whose name was Eisen, after she left his temple she meant to kill herself.

“Perhaps you were fated to come here,” Eisen mused. “It can’t be coincidence that I met and talked with the monk Jebu and Lord Muratomo no Yukio years ago, just before their journey to China. Lord Yukio did not seem to me a man who would murder a helpless youth, but then, you do not seem to me the sort of woman who would kill herself because her son is dead. The Buddha himself had a son, you know.”

“I thought you said the Buddha does not exist.”

“Assuredly, a man called Siddhartha lived many hundreds of years ago, and he had a son whom he called Obstacle, because, he said, the love of a child is a great hindrance to enlightenment.”

“I would rather love my child and not be enlightened.”

“To say that shows that your enlightenment is already great. If you are willing to love, you must expect to suffer. If you are willing to suffer, you are willing to live. Your life is not yours to dispose of, you know.”

“If not mine, then whose? The Buddha’s?”

“All lives are the Buddha’s life, because you are the Buddha.”

At his words, there was an explosion of light within Taniko like a Chinese rocket shooting into the sky and then bursting into a chrysanthemum of glowing colour. She felt an enormous surprise. It was all so simple. She felt peace and gladness, as if she had just found the answer to all the questions that had been tormenting her for years. What she had learned or why she felt this way, she could not put into words. She looked at Eisen, amazed.

His broad smile was delighted, congratulatory. “Some monks spend their whole lives sitting in meditation before experiencing what you have just experienced.”

“What happened to me?”

“Nothing special. The feeling will fade after a time. It is a very good feeling, but you will fall into hell if you try to hold on to it. You are like a person lost in a forest, who stumbles across a hidden temple.

Having found it once, you will be able to find your way back more easily, but do not try to stay there, because you have work to do. Work is the true Western Paradise in which we achieve salvation.”

Taniko remembered that Hideyori, the opposite sort of man from this monk, had said she could escape her sorrow through work. How strange. She stood and looked out the door of the little temple. The quiescent ocean gleamed like a bronze mirror as the rim of the sun appeared at its edge.

“May I come to see you again? I know there is much more you can teach me.”

“Life is the teacher,” said Eisen. “Everything that happens to you is what we call a kung-an, a question whose answer points to the Buddha within

Comments (0)