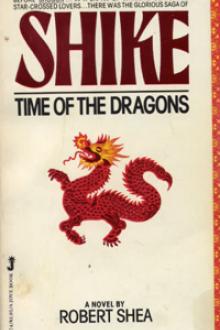

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

“Eor this desecration the Takashi paid dearly. That evil brood who hated mankind and the law of Buddha now suffer the torments of Emma-O, the king of the underworld, and his jailers. Such is the fate of all who harm the servants of the Lord Buddha.” Jebu delivered the last statement in a thunderous voice and swept Shinohata and the circle of samurai with a threatening gaze.

“The Todaiji as it was can never be replaced. We hope, even so, to build another splendid temple on its ruins. The great Buddha will be rebuilt of copper and gold with a sacred jewel in his lofty forehead.

“Even as the Buddha and his disciples went forth daily with their begging bowls, so I, Mokongo, stand before you weeping, asking your contributions. If they who destroyed the Todaiji earned bad karma, surely those who help rebuild it will enjoy good karma in equal amount according to the most true law of cause and effect. They will attain to the further shore of perfect enlightenment. As for those who hinder us, they will be cast into the fire pits, there to gibber for a thousand times a thousand lifetimes.

“A small contribution will be enough to earn the Buddha’s infinite mercy. Who is there who will not give? It is said that even he who gives a little sand to help build a pagoda earns good karma. How much more he who gives something of value?

“Composed by me, Mokongo, for the purpose of obtaining contributions as stated. The Tenth Month of the Year of the Rooster.” Again Jebu gazed sternly about him. His hearers fell back under the look in his blazing eyes. He closed the scroll with a snap and handed it to Totomi, who quickly put it away.

Timidly at first, samurai in the audience began to come forward holding out small gifts-rings and necklaces, Chinese coins, carvings. Grandly, Jebu gestured to Totomi to collect the offerings.

“I did not read my solicitation scroll to obtain gifts here, only to set your mind at rest,” Jebu said to Shinohata. “But since your men seem moved to help us, perhaps you can supply us with travelling boxes to hold what they give us.”

“There is one more precaution I must take,” said Shinohata. “I must inspect your entire party before I let them pass.” He stepped down from the porch, and with a samurai’s swaggering gait led the way to the entrance to the stockade. Reluctantly, Jebu walked beside him, followed by Totomi.

“This is distasteful to me,” said Shinohata, his harsh features softening as he spoke quietly to Jebu. “Of course, the Lord Shogun has every right to do whatever he deems necessary to preserve order in the land. Still, I bitterly regret the turn of events that set the two great Muratomo brothers against each other. I had the honour of serving under Lieutenant Yukio during the War of the Dragons. A most gallant commander.”

Jebu glanced over his shoulder at Totomi, whose eyes bulged in a flushed face. He seemed almost ready to spring upon Shinohata’s back. Eorcing a casual tone, Jebu said, “Were you at Shimonoseki Strait, captain?” Perhaps the man had not actually seen Yukio.

“Unfortunately, no. The lord I served withdrew from Yukio’s army after the battle of Ichinotani. We left to help subdue the Takashi forces in the western provinces, where we fought beside the barbarian horsemen who accompanied the lieutenant from China. But forgive me, Priest Mokongo, I’m sure you have no desire to hear this talk of war.”

Jebu smiled. “The Buddha himself was born into a family of warriors.” By this time they had passed through the gates of the fort and were among short, twisted pines, treading the steep path that led down to the place where the barrier pole blocked the road. There were about thirty soldiers following them. Another six were down below, guarding the travellers, who squatted on the ground, patient and quiet as true yamabushi.

“Yes, but the Enlightened One did not stay a warrior,” Shinohata was saying. “Sometimes I feel ready to give up this life myself, to trade it for the serenity that you must enjoy. Eor now, I must faithfully carry out the order of the Shogun. Believe me, Priest Mokongo, there are those who watch everything I do.” He glanced back at the troops following them down the mountainside. “Much as I might wish to speed you on your way, I must err on the side of severity to be sure of pleasing the Shogun.”

“I understand, Lord Shinohata,” said Jebu, not at all easier in mind. “We desire nothing more than peace, and perhaps peace can be best achieved when warriors remain vigilant.” Now they had reached an outcropping of jagged black rock just above the road. Shinohata poised himself there, his booted feet planted wide apart. Behind him the soldiers formed a semi-circle, holding their bows, swords and naginatas.

“Raise the barrier,” Shinohata ordered the guards blocking the road. “Let those monks pass through it one by one.”

Jebu and Totomi scrambled down to join their comrades. “Let’s seize him now,” Totomi whispered. “His men won’t attack us if we hold him hostage.”

“He’d insist on dying, as any good samurai would,” said Jebu with an irony that escaped Totomi. Jebu ordered the false monks into line. Passing close to Yukio he whispered, “He may have seen you before. Keep your head down.” He stood at the base of the rock from which Shinohata watched as the monks in their tattered robes trudged by.

“Have them take their hats off,” said Shinohata. Jebu gave the order, and those wearing conical rice-straw hats as protection against the elements bared their bald skulls. Yukio was tottering at the end of the procession, bent under the portable altar.

“You’ve got your smallest monk carrying that great, heavy altar,” Shinohata remarked.

“He’s not a monk,” said Jebu. “Just a lay brother, a porter.”

Just as Yukio, who had fallen far behind the others, came abreast of Shinohata, he tripped over a stone in the path and fell. The altar landed on its side with a booming crash. Yukio, on all fours, looked directly into Shinohata’s face. Jebu heard Shinohata gasp. He saw the samurai officer’s eyes fill with amazed recognition.

At that moment the Self took charge of Jebu. He sprang at Yukio, brandishing his walking staff. One part of his mind brought the stick down on Yukio’s back.

“Careless monkey!” he shouted. “How dare you let the altar of the Lord Buddha fall to the ground? Weakling! You repeatedly delay us, and now you drop our holy altar. On your feet and pick up that altar, or I’ll break every ,one of your delicate ribs.” He thumped Yukio with the stick until Yukio crawled to the fallen altar and got his back under it. With horrified glances at Jebu, two of Yukio’s men went to help him shoulder the burden.

“Get back,” Jebu roared, waving the stick at them. “A mere porter has no right to the help of monks.” At last Yukio got the four-legged chest on his back and securely tied around him. Bent double, he staggered forward again. Shinohata looked shocked.

“I thought for a moment-” he stammered. “But no samurai would strike his lord as you have thrashed this porter. Not even to save his life.” He glowered at his men as if challenging them to question his thinking. The soldiers stood silent, amazed at the giant priest’s outburst of anger and beating of the little porter. Also silent, staring thunderstuck at Jebu, were the other false yamabushi. Shenzo Totomi, already some distance past the barrier, appeared almost maddened with rage.

Shinohata looked back at Jebu. “You are a remarkable man, Priest Mokongo. I am sorry that we threatened you and delayed you. I will send a runner after you with a few jars of sake, by way of apology.”

“Monks do not drink sake,” Jebu reminded him.

“Of course not. Even so, it may be permissible for you to take a drop to ward off the chill in this mountain air.” He glanced down the road at the little figure stumbling under the altar, and Jebu saw tears standing in his eyes. “The mountains are so vast and hard, and man is so small and fragile.”

Bars of sunlight streamed from behind the black peaks to the west and gilded those to the east. The fort was hidden behind a pine-ridged slope. Jebu prostrated himself before Yukio, who had shrugged out from under the portable altar. Tears poured down Jebu’s cheeks.

“Eorgive me, Yukio-san,” he sobbed. “I don’t know how I could have done that. Punish me as you see fit.”

Totomi sprang forward. “Let me kill him, lord. Eor striking you, he deserves to die.”

Yukio laughed. “What will you do, Totomi, beat his brains out with a rock? Have you forgotten that the monk Jebu cleverly ordered us to throw all our weapons away? Almost as if he knew we were going to do something outrageous. Jebu, you’ve probably been waiting years to give me a good whack across the shoulders with a stick.” Tentatively at first, then uproariously as relief swept over them, the men laughed. Even Totomi joined in at last. No one really wants to die, thought Jebu. It is one thing to be willing to die, as these men are, and another thing really to want death.

The pounding of booted, running feet echoed in the silence of the mountains. Three soldiers in tunics and trousers were hurrying along the path in the twilight. The chilling thought crossed Jebu’s mind that Shinohata had sent troops after them to arrest them. Then he saw that the men were unarmed and that large sake jars were bouncing on their shoulders.

“Compliments of Lord Shinohata to your holinesses,” one man panted as they presented the wine to Jebu’s party. Some of Jebu’s men built a fire, and Jebu invited the three soldiers to share the wine with them. Regrettably, the soldiers agreed to stay, and so the fugitives could not freely celebrate their escape but had to keep up the pretence of being monks. Yukio, still playing the porter, served a supper of dried fish and rice cakes. Jebu felt the wine glowing in his middle like a jolly round red lantern. He was overjoyed at having survived the ordeal of the barrier and miserable at having struck Yukio. The contradictory feelings were pulling him to pieces like those horses the Mongols sometimes used to tears apart a heinous criminal. He could not sit still. He jumped to his feet, picked up his staff and held it horizontally in both hands before him. He began to dance, first stepping solemnly to the left, then hopping more quickly to the right, then whirling about. It was a young man’s dance he had learned at the Waterfowl Temple an age ago. His companions stared open-mouthed, but the soldiers laughed delightedly and clapped their hands in time to Jebu’s steps. Yukio produced a taiko drum and beat out a complex rhythm. Eiercer and wilder grew Jebu’s dance as he poured into it everything he felt-grief at Yukio’s downfall, anger at Hideyori and his minions, longing for Taniko, joy at being alive, sorrow at the tragedy that is all of life. He astounded the onlookers with a series of midair somersaults, then ended with side steps as slow and stately as those he had begun with.

Holding up a torch to light their way, the soldiers said good night reluctantly to this remarkably merry band of monks. When they were gone, Jebu again threw himself to the

Comments (0)