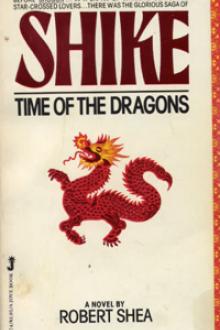

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

Taniko answered him in that language. “Our family is involved in trade. My father has seen to it that all his children are educated in the skills that are useful in commerce. Knowledge, he says, can be wealth.”

Horigawa pulled his robe around his spindly limbs. “Who would have thought that a child-woman from the provinces would possess such a valuable skill?” He was still speaking Chinese. “Mine is a family of princes and scholars, and Chinese has been our other language for centuries. Do you read and write it as well?”

“Better than I speak it.” Actually, she surprised herself by being able to carry on the conversation.

“Excellent. When you are my wife you will serve me as secretary. The trade with China is a great source of wealth for the Takashi, and with my own knowledge of things Chinese, I humbly endeavour to help them. As Lord Sogamori’s authority continues to grow, we shall see a reopening of closer relations with China, which our rulers have long neglected, to our cost. The communications I undertake with China are delicate and require secrecy. It is difficult to acquire servants who have the necessary education and are also trustworthy. You will be very useful to me.”

“Thank you, Your Highness,” said Taniko, trying not to grind her teeth.

The thought that Horigawa was already planning her future appalled her. She tried to remind herself that many of the women in the Sunrise Land had husbands as repulsive, or worse. It did no good.

As before, Horigawa excused himself from spending the night with her, citing the pressure of his world in the service of the nation. After he was gone, Taniko sat in the dark, crying softly. To refuse the marriage her family had decreed for her was unthinkable. But the prospect of a lifetime tied to Horigawa filled her with such despair and dread that she was almost ready to kill herself to avoid going through with it.

Almost, but not quite. Even in her anguish she felt a deep certainty that she wanted to go on living. And she was as strong as Horigawa; in time she could put a stop to his horrid little practises. He was more than forty years older than she; he could only grow feebler and easier to manage with the passage of time. And in the fullness of time she would be rid of him. She had only to endure; to do her duty as a samurai, as Aunt Chogao put it.

The prospect of working on Horigawa’s Chinese correspondence was fascinating. The little she knew about China was information over a hundred years old that had been taught to her and her sisters by monks. How wonderful it would be to learn what was happening to China now.

Five nights later a messenger came from Prince Horigawa, and Ryuichi ordered the third-night rice cakes placed in Taniko’s bedchamber. After sunset the prince’s ox-drawn state carriage drew up before the western gateway of the Shima mansions without even a pretence of secrecy, and the prince, wearing his usual tall black hat and a scarlet and white cloak, more festive looking than the black and gold one he had worn previously, strode through the lamplit gate, while the Shima family peered at him through screens and blinds.

His performance with Taniko was as brief as at their first encounter. This time, though, he bit her breast at his moment of supreme pleasure. This left teeth marks, which he looked at with satisfaction afterwards.

As was expected of her, Taniko paid him a pretty compliment on his manly strength. Inwardly, she was quaking. They were now committed. She was bound to him. It was his third-night visit, with the ceremonial eating of rice cakes, which actually sealed their marriage. It was all over, and now that it was done she could see no future for herself. She felt a sensation of sinking into a bottomless black pool. She had done her duty as a samurai woman, yes, but might duty not be easier for a man, who died only once and quickly, than for a woman who had to die a little bit each day for years and years?

Horigawa nodded in acceptance of her compliment. “You are fortunate to have a wellborn man of the capital as a husband. Think how miserable you would have been in the arms of some rough country man smelling of the rice paddies.”

Remembering Horigawa’s role in the executions of four years ago and his talk about massive bloodshed, Taniko thought, I would prefer the smell of the rice paddies to the stink of the execution ground.

Horigawa reached into the sleeve of his robe and drew out a scroll. “This is a report I received from a monk in China. I intend to present it to Lord Sogamori. You will translate it into your language and write it out in your best hand. I trust your handwriting is acceptable?”

“My handwriting has been praised,” said Taniko, “but it is, of course, only the poor effort of a girl raised in a rustic fishing village.”

The sarcasm escaped Horigawa. “Lord Sogamori is a man of some discernment, even though he is merely the chieftain of a samurai family. You must be sure to form your characters as beautifully as you can.”

Taniko put the scroll in the drawer of her wooden pillow. She could hardly wait for some time to herself, to read the letter from China.

Horigawa ate the ritual rice cakes with her, honouring Izanami and Izanagi, progenitors of all the kami and creators of heaven and earth. She almost wished her own cake were saturated with poison. Then Horigawa removed his hat of office and lay down, resting his head on the wooden pillow she had placed beside her own. With a wave of his hand, he indicated that she was to blow out the candle.

They slept in the same clothing they had worn all day, as was usual. Side by side they lay in the dark on quilted futons. Horigawa was a restless sleeper who mumbled and moaned as if bad dreams troubled him all through the night. Bad dreams might portend future disasters for Horigawa. The possibility pleased her, because her only hope was that he might not live long. Perhaps he was haunted by the ghosts of those whose executions he’d demanded.

Taniko lay awake most of the night. As she had tried to do on her first night with Horigawa, she sent her mind on a journey-this time to Mount Higashi and the night she had spent there with Jebu.

In the morning the Shima family, led by Uncle Ryuichi, Aunt Chogao and their eldest son, five-year-old Munetoki, burst in on them with the expected cries of joy and congratulations. Having spent three nights together and partaken of the sacred rice cakes they were now officially married. However, Taniko would remain in the Shima household, as was the custom among people of their class, and Horigawa would visit her as often as he chose to bestow his princely favours. Taniko hoped lust would provoke him infrequently. She would go to his house when needed there for ceremonial and social occasions.

Taniko’s uncle and aunt each picked up one of Horigawa’s shoes. By taking the shoes to bed with them that night, they would try to ensure that Horigawa would never leave Taniko. Each sign that the world wanted this marriage to be permanent made Taniko’s heart sink a little lower.

Horigawa imperiously handed Ryuichi a scroll. “This is a list of the guests I wish you to invite to the wedding feast. You will hold the feast on the thirteenth day of the Ninth Month, four days after the Chrysanthemum Festival. My diviners tell me that will be the last auspicious day for quite some time.” He took another scroll from his sleeve. “I have also included a set of instructions on how the feast is to be conducted. It is essential that every detail be both correct and fashionable. I prefer not to rely on the judgment of a provincial family in such matters.”

After Horigawa was gone, Ryuichi raged and wept. He was furious at the prince’s contempt for his family, and appalled at the cost of the wedding feast, which, he claimed, would wipe out the family fortune if he followed Horigawa’s instructions.

“Why did you have to marry that leech?” Ryuichi howled at Taniko.

Taniko bowed to hide her amusement. “Forgive me, Uncle. I regret that he causes you such pain. My father commanded me to marry him for reasons that seemed wise to him.”

Ryuichi subsided. “We expect the marriage to do us good. But if my esteemed older brother had only let me arrange a match for you, instead of doing it by himself from such a great distance-” He smiled suddenly. “You, also, might have been happier with the result. You’re a good daughter, Taniko, to put up with marriage to such a repulsive person.”

“I intend to do more than put up with it, Uncle. I have always wanted to live in the capital and be part of the doings at the Court. I have never wanted the lot of an ordinary woman. If Horigawa is the price I have to pay to live here, I accept that price. Perhaps I will do well for myself despite the match my father made.”

Her little cousin Munetoki stared at her, his eyes shining with admiration.

On the day of the wedding feast some of the best-known names in Heian Kyo came to see the mating of a major councillor of the Fourth Rank to the daughter of an unknown, but reputedly wealthy, family of the provinces. Taniko had studied the guest list carefully. As the presiding priest, the abbot of the huge Buddhist monastery on nearby Mount Hiei intoned blessings and purifications, and the guests clapped their hands ritually. Whenever she dared, Taniko glanced here and there among those present, trying to match faces and costumes with the names she knew.

Many members of the Sasaki family and their principal wives had come to sit behind Horigawa to represent the clan. And another old and powerful family was there in large numbers-the Fujiwara. While they were not Emperors themselves, the Fujiwara had held supreme power in the capital until recent times. So many Fujiwara daughters had married Emperors that, among those who dared to be irreverent, the Imperial house itself was sometimes described as a branch of the Fujiwara.

In recent times, though they still enjoyed great prestige, the real power of the Fujiwara had declined. Their strength lay in courtly intrigue rather than force. But these days, with the rise of the samurai families, force counted for more.

Among those supplanting the Fujiwara in national importance were the Takashi, also heavily represented at this wedding feast. They sat in the front row of guests facing the abbot and the altar. Sogamori, chieftain of the Takashi clan and Minister of the Left, was a round-faced man whose partially shaven head was hidden under his black hat of office. He wore a red cloak embroidered with gold and lined with white satin. He looked as florid and petulant as Taniko had expected, given his reputation for bad temper.

The man in a similar scarlet robe beside Sogamori must be Kiyosi, his eldest son. Taniko’s heart beat a little faster when she saw him. There was a family resemblance to Sogamori, but Kiyosi was lean, vigorous-looking, and square of jaw. Oh, to marry a young man like that, instead of a spider like Horigawa. Such a young man, she thought, might almost help me forget Jebu for a time.

Kiyosi sat proudly upright as befitted a military man of noble rank. Yet there was kindness and intelligence in his face as well. She suspected that,

Comments (0)