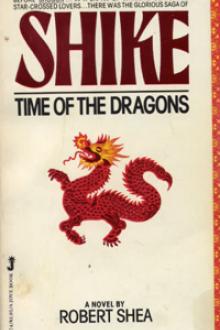

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

She managed to smile at Bourkina and they started walking again towards the palace of the women.

Bourkina said, “I told you once that we are making a new world. The world you came from will only cause trouble for you.”

Seremeter said, “She has a lover among those warriors from her country, is it not so, Taniko?”

“Certainly not,” Taniko said, angry at Seremeter for harping on a subject she wanted dropped. Didn’t any of these people know the value of silence?

“She’d best put him out of her mind if she does,” said Bourkina. “She belongs to the Great Khan now.”

“Along with how many hundred other women?” said Seremeter. “At the last count, four hundred and fifty-seven. When the Great Khan spreads his attentions so widely, a woman can’t be blamed for at least thinking of a former lover.”

“I wonder who will receive his attentions on this night of nights,” said Taniko to change the subject.

Bourkina chuckled shortly. “I wouldn’t want it to be me. These Golden Eamily men, when they win a victory, they’re like bulls in springtime. His father and grandfather were that way.”

“Do you speak from personal knowledge, Bourkina?” said Seremeter sweetly. Before Bourkina could answer she went on, “Bulls in springtime. I think I’d like to experience that.”

Bourkina shook her head. “He’d tear you apart.”

“Taniko, I really do believe Bourkina has bedded all three, Genghis Khan, Tuli and Kublai Khan. Tell me, wouldn’t you like to see our lord like a bull in springtime?”

Taniko was embarrassed to admit that Kublai had yet to take her to bed. “I’m thoroughly pleased with him as he usually is.” Bourkina looked at her shrewdly. She probably knows, Taniko thought.

They had arrived at the women’s palace. Guards admitted them and they went up to their chambers. Music, shouts and laughter from the hall of the kuriltai reached them even here. Taniko undressed with the help of a maidservant and lay down to rest. The events of the night had been so exciting that she found it hard to drop off to sleep. Her last thought before drifting into dreams was, Jebu is alive.

Bourkina awakened her suddenly.

“Is it morning? How long have I slept?”

“No, you’ve been in here just a few hours. You must get up, my child. He has sent for you.”

“Eor me? Why me?”

“It is not your place to question. You are to attend the Great Khan in his chambers. Don’t keep him waiting.”

She entered Kublai Khan’s chambers with as much fear as she had felt at their first meeting. The pale green silk hangings suspended from the ceiling and covering the walls gave the room a dome-like shape. The floor was covered with thick Chinese carpeting. He’s managed to make it look like a yurt, she thought.

Hidden musicians played wind and string instruments. A pleasant tang of incense floated on the air. In the centre of the room stood a silver swan on a marble pedestal.

A circular dais guarded by porcelain lions took up half the room. Heavy brocade curtains gathered above would drop down at the pull of a cord, to form a yurt within a yurt, screening Kublai’s bed from the rest of the room.

There were no windows, therefore there was no way to tell whether it was night or day outside. A man living in a room like this could make his own time.

Kublai sprawled on the cushions on the dais. He was wearing a simple dark green robe, belted at the waist. The embroidered garments and jewels that had adorned him earlier in the evening were gone. Taniko bowed to him.

“Well, my little lady, what did you think of tonight?” he said in his deep voice, rising to his feet with a smile. She would have thought the question casual except for the way his black eyes glittered. She found herself at a loss for words, and the terror at being in his presence persisted. Uncertainly, she bowed again.

“Do speak,” he said. “Try to think of me as just an ordinary man.” He walked towards her slowly. She wondered again, why me? Of all those four hundred and more women, why me?

She tried to smile back at him. “It’s no use, my lord. Your Majesty. The ways in which you are not ordinary shine out too brightly. There is nothing I can say that can possibly match the event I witnessed tonight. I feel foolish. I can’t imagine why you should have sent for me, when there are many women more beautiful and more clever than I who might have shared this moment with you.”

Kublai shrugged. “There may be a few as beautiful. None so clever.” “If cleverness is what you want, there are a thousand sages here in Shangtu able to talk much more cleverly than I can.”

“Yes, and some of them may even be honest men. But there are only a few as clever as you, and none at all are beautiful. Tonight I want the company of a woman. Women are very important in my family, you know. In many ways, it was the women of the house who shaped us.”

“I don’t understand, Your Majesty.”

“We were raised by our mothers. My grandfather, Temujin, whom we call Genghis Khan, was eleven years old when his father was poisoned. His mother ruled over the tribe until Temujin was of age. And my grandmother had to care alone for all four of the sons of Genghis Khan, while my grandfather was gone campaigning.

“When my father, Tuli, died, we were still young, my brothers and 1. I was sixteen. We were in great danger, because the house of Ogodai feared us as possible rivals. My mother, Princess Sarkuktani, guided us through those dangerous years. She engaged Yao Chow to teach me to write and to read the Chinese classics. She taught my brothers and me to show deference to the ladies and princes of the house of Ogodai and to bide our time.”

Taniko said, “It’s all so different from my land. Here women can be powerful. The grandson of a destitute orphan can be ruler of the largest empire that has ever been.”

“A destitute orphan, yes.” There was a faraway note in his voice. She sensed that having made his claim to the supreme place in his world, he wanted to talk about who he was and where he had come from.

“My grandfather was the lowest of the low,” he went on. “He had nothing, nothing at all. His tribe was scattered. When the Taidjuts caught him, they didn’t even think him worth killing. They put a wooden yoke on his neck and made a slave of him. He was strong and resolute, but he was as far down as it is possible for a man to be. He did not even own his body. Could he have foreseen then that he would one day make his name feared among all nations, that men would call him Genghis Khan, the Mightiest Ruler? With all the powers of his mind, he could not have predicted that.

“What he intended at the beginning will always be a mystery. I do not think he knew what he could accomplish. After he escaped from the Taidjuts, he just set out to fight back. He was like a man climbing a mountain who does not think of what he has left behind or where he is going, but simply takes the next step, climbs over the next rock. Suddenly, to his surprise, there are no more rocks to climb. He has reached the summit, and he looks around and down and he sees all at once what he has become, and he is full of joy in himself and his achievement.”

Taniko wondered if that was how it was for Kublai this night when he was proclaimed Great Khan.

Kublai walked over to the sculptured swan in the centre of the room and beckoned her. He held a goblet under the swan’s beak and struck a bell with a small hammer. After a moment a pale stream of wine spurted from the beak and splashed into the cup. T����niko laughed as he handed the cup to her and tapped the bell for another goblet for himself.

“It’s almost like magic, Your Majesty.”

“No need to have servants running in and out, disturbing us. In his palace at Karakorum my brother Mangu had a tree of silver with four serpents twining up its trunk. Erom the mouth of each serpent came a different kind of wine, and at the top was a silver angel that blew a trumpet whenever the Great Khan drank.”

Kublai reached out a hand to stroke the silver swan. “Drinking has destroyed many members of my family. Every one of the four sons of Genghis Khan died an early death. My grandfather died at seventy-two, but none of his sons reached the age of fifty. The eldest, Juchi, died before Genghis Khan did, a gout-crippled wreck, in Russia. My father, the youngest of the four, was the next to die, at forty. He was addicted to wine. Chagatai and Ogodai died a year apart. Ogodai was only forty-six. I never saw either of those uncles sober. Once one of Uncle Ogodai’s ministers showed him an iron jug that was corroded because wine had been standing in it. Ogodai promised to drink only half as often as he had been. Then he had a goblet made for himself that was twice as big. My cousin Kuyuk, the third Great Khan, was a drunk. He was already a dying man when the kuriltai elected him. He reigned less than two years.”

Taniko sat on a cushion, looking down at the golden wine in the silver goblet. “But a man getting drunk is nothing to worry about. Men need to get drunk once in a while to relax.”

“That was so among my people before the victories of Genghis Khan. That still seems to be so for my brothers and me. We have escaped the family curse. But in the old days Mongols drank kumiss, fermented mare’s milk, which is not as strong as wine. They drank when they could spare the time, which was not very often. After the wars of Genghis Khan, wine went through our people like a plague. We had nothing else to do. We had servants or slaves to do our work for us. We were forbidden by the Yassa to fight among ourselves. We could not spend all our time with the women. What is left, if you can’t read or write, if you are more ignorant of civilization than the poorest Chinese dung carrier? Water flows downhill, and men prefer to do what is easy. The easiest thing to do is drink. It makes life seem interesting. Now we drink from sleep to sleep. We poison ourselves by the hundreds and thousands, we lords of the earth.”

Again Taniko looked down at the wine. Astonishing, that it should be the death of so many of these hardy Mongols, that they should be, in their way, such vulnerable creatures. Like wild flowers that withered instantly when plucked and brought indoors.

“There are other reasons why many of us drink too much,” Kublai went on. “We’ve seen too much. Often, when we take a city, we kill all its people. Tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, sometimes.”

Taniko looked at him in horror. “I’ve heard that. I

Comments (0)