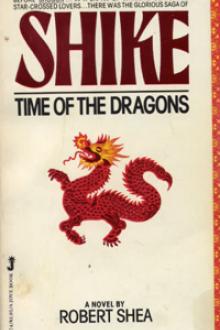

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

Another sign of her family’s new position were the guards at the gate. No less than ten samurai stood there, looking relaxed, alert and very competent, all carrying two swords and dressed in handsome suits of full armour, the strips of steel lashed together with bright orange lacings. Their captain’s helmet was decorated with a white horsehair plume.

The party with Taniko included Jebu, Moko and five samurai guards, men who came from the area around Kamakura and who volunteered to accompany Jebu and Taniko so they could visit their homes. All rode horses, and three more horses carried their baggage.

No one would suspect from looking at them, Taniko thought, that each was moderately wealthy with spoils brought back from China, or that they were the harbingers of a powerful army newly landed on the Sacred Islands. They were tired, and their travelling robes were dusty and stained. It had taken them twelve days to get here from Hiraizumi, coming down from the mountains of Oshu by horseback, then hiring a coasting galley to make the long voyage from Sendai. The stunning scenery of the far north helped Taniko, to some extent, to forget her sorrow. The soaring crags and rushing, foaming streams, the huge rocks laced with white ribbons of falling water were wilder than any landscape she had ever seen-even a bit frightening. When their party reached the sea there were countless islands scoured into strange shapes by wind and wave, and covered by precariously clinging pines leaning at odd angles. A Heian Kyo courtier would find such sights barbarous, but having lived among barbarians Taniko could see the beauty in it. As they rode along, she and Jebu were silent most of the time. There was nothing left for them to say to each other now. Time was their best hope. She expressed the thought in a poem she gave him on shipboard, a poem inspired by the scenes through which they had passed.

To carve a hollow in the island rock, A shelter for the sea birds,

Many winters, many summers.

She handed it to him silently just before their galley docked at Kamakura, and silently he read it, nodded and put it inside his robe.

Now the captain of the Shima estate’s guards was swaggering towards them. Jebu climbed down from his horse and approached him.

“Another monk, by Hachiman,” the captain snarled before Jebu could open his mouth. “Every ragged monk from here to Kyushu has heard that there are rich pickings to be had in Kamakura. Well, not at this house. Lord Shima Bokuden has given strict instructions that monks are to be sent away with their begging bowls empty. Go.” The captain laid a threatening hand on his silver-mounted sword hilt.

A typical samurai of the eastern provinces, Taniko thought, blustering and rude.

Taniko watched as Jebu turned his left side towards the samurai captain, bringing the sword dangling from his belt into view without making a threatening gesture. “Excuse me, captain,” he said politely. “I am escorting Lord Bokuden’s daughter, the Lady Taniko, who has come a long way to visit her father. Would you be kind enough to allow us to enter and to notify Lord Bokuden that his daughter is here?” Jebu did not mention his own message for Hideyori. They must manage to find out Hideyori’s situation without expressing any interest in him.

“Oho, one of those weapon-carrying monks, eh?” the captain growled. “What sort are you, Buddhist, Shinto or Zinja? None of you armed monks is either holy or skilled in the martial arts, so there is no need to fear either your curses or your swords. That woman on horse back claims to be Lord Bokuden’s daughter, does she? Lord Bokuden’s daughter is a great lady who lives at the capital. She would not come riding up here on a horse, like some camp follower.”

“Pay no attention to him, my lady,” said Moko in a low voice. “His mother was a yak.” Taniko wanted none of the men with her to quarrel with her father’s guards. She decided to assert herself and spurred her horse forward. She addressed the captain in a small but sharp-edged voice, like the dagger all samurai women carried.

“The Lady Shima Taniko has not resided in Heian Kyo in seven years, captain, as you should know. As for my riding a horse, I am samurai by birth and upbringing and can perhaps ride as well as you. I advise you to change your tone and let us in at once, or you’ll answer to my father when I report this to him. If, that is, you do work for my father and are not some filthy ronin who happened to be idling by the Shima gate when we rode up.” There were some mild chuckles from Taniko’s party, and even some from the gate guards, at this last jab. The captain blushed.

“I have my duty to perform, lady. A party of assassins might try to enter here in disguise. If you’ll dismount and the men will disarm themselves I’ll admit you, and you can wait inside the gate to be properly identified.”

Her father had always suspected the worst of his neighbours, but he had never worried about assassins. Another change in the Shima family since she left.

Grooms took their horses through the double set of gates, leading them to the stables. Two of the guards collected swords from all the men except Moko, who did not carry one. Once inside the gate they walked single file through a maze made up of wooden walls and the sides of buildings, a maze designed to trap any attackers who might get through the gate during a siege. At last they found themselves in a courtyard full of boxes and barrels. It appeared that the Shima were still in trade, more so than ever.

“You have good horses and good swords,” the captain remarked. “If you’re a band of thieves, you chose victims of good quality.”

This was too much for Moko. He reddened, turned to the captain and said, “Not being a man of much quality yourself, you couldn’t be expected to recognize it in others.”

The captain stared at Moko. Taniko’s heart started pounding. Moko had forgotten where he was. He had come up in the world, had travelled with Yukio’s samurai and talked with them on equal terms. Everyone, of whatever rank, talked freely among the Mongols. A commoner did not speak sharply to a samurai in the Sacred Islands, however, and Moko might lose his life for it.

Without a word the captain moved towards him, sliding his long sword out of the scabbard that hung at his left side. Moko paled, but did not try to run. The captain drew his sword back, holding it with both hands, for a stroke that would cut Moko in half at the waist. Jebu stepped between them.

“Out of the way, monk,” said the captain. “No commoner can insult a samurai and live.”

“I beg you to reconsider, captain,” said Jebu quietly, “or you’ll end by looking even more foolish than you do now.”

“Out of my way, or you’ll die before he does.”

“Please put your sword away, captain.”

Taniko was terrified. Jebu’s own weapon had been carried away. He might be cut down before her eyes.

The captain lunged at Jebu, swinging his sword. Jebu hardly seemed to move, but the blade cut through empty air, and the captain rushed past him. Jebu quickly shifted position again, to keep himself between the captain and Moko. The captain swung at Jebu’s legs, and Jebu leaped high into the air. Now the captain had forgotten Moko and was determined to kill Jebu. Jebu ran up the side of a pyramid of boxes and kicked them, sending them tumbling down on the captain, who tripped and fell under the avalanche. He picked himself up and came after Jebu again.

Easily ducking and dodging the sword, Jebu led the captain back across the courtyard towards a high wooden wall. The captain brought his blade down in a ferocious two-handed swipe. The sword thumped into the hard wood of the gate. The captain was furiously trying to pull the sword out of the wood when Jebu, robe flapping, swooped down on him like a falcon on a rabbit and picked him up, leaving the sword stuck in the gate. Jebu hefted the captain into the air and hung him by his belt from an iron hook used to suspend a lantern over the courtyard at night. He pulled the samurai’s shorter sword out of its scabbard and laid it on the ground, then freed the long sword from the door and laid it across the short one. Bowing to the captain, who wriggled frantically to free himself from the hook, Jebu turned and walked away. The courtyard shook with laughter. Elated by Jebu’s unarmed triumph over the samurai, Taniko clapped her hands with glee.

“Taniko.”

Standing at the top of the steps entering the donjon was her Uncle Ryuichi. Her heart gave a surprising little leap of gladness. She wondered what he was doing here instead of Heian Kyo. Then she remembered with a sinking feeling how she had accused him of failing her and had walked coldly out of his house seven years ago. Yet she was happy to see him today.

Ryuichi had grown fatter in the interval. His eyes and mouth were tiny in his white moon of a face. Powdered and painted like a courtier, he wore gorgeous robes that glittered with gold thread.

Taniko bowed to him. “Honoured Uncle. I have returned from China.”

Ryuichi looked at her, astonished, then his expression changed abruptly to a frown. “What is happening here? Why is that man hanging there?”

The captain managed to unbuckle his belt, drop to the ground with a clatter of armour, and kneel. Taniko noted that the whole courtyard had fallen silent as soon as Ryuichi appeared. He had an air of command she had never seen in him before.

“Your captain of guards was about to kill one of my escort,” she said. “This Zinja monk, who is also a member of my party, hung him up there to give him time to calm himself.”

Ryuichi took immediate charge. He sent the guards back out to the gate, and looked reprovingly at the captain who had allowed himself to be disgraced. He ordered Taniko’s party fed and quartered in the estate’s guesthouses.

“Niece, if you will forgive me, I think we ought to talk immediately. After that you can refresh yourself. Please come with me.”

Not looking back at Jebu, Taniko followed Ryuichi into the donjon. They climbed up winding flights of stairs in the dark interior. At last he drew her into a small chamber whose window overlooked the courtyard. They knelt facing each other across a low table.

“My esteemed elder brother will be astonished when he learns his daughter has returned. I am happy to see you.” He looked at her uncertainly. “I hope you are happy to see me.”

“I am, Uncle. Very.”

Unexpectedly, tears began to roll down his whitened cheeks. “I never thought to see you again. I was sure you would die in China, and I blamed myself. You were a daughter to me, but I could not save you. I was tormented. I felt I had two choices: to die or to try to become the sort of man who does not let such things happen. I decided I was not worthy to die. So I have tried to become a better man.”

She smiled. “I noticed a difference about you, Uncle.”

He nodded. “I am no longer afraid. I have learned

Comments (0)