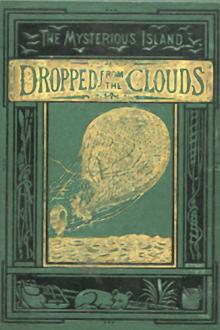

The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne (rosie project txt) 📕

- Author: Jules Verne

- Performer: 0812972120

Book online «The Mysterious Island by Jules Verne (rosie project txt) 📕». Author Jules Verne

During this month the heat was very great. Nevertheless, the colonists, not wishing to cease work, proceeded to construct the poultry-yard. Jup, who since the enclosing of the plateau had been given his liberty, never quitted his masters nor manifested the least desire to escape. He was a gentle beast, though possessing immense strength and wonderful agility. No one could go up the ladder to Granite House as he could. Already he was given employment; he was instructed to fetch wood and carry off the stones which had been taken from the bed of Glycerine Creek.

“Although he’s not yet a mason, he is already a ‘monkey,’“ said Herbert, making a joking allusion to the nickname masons give their apprentices. And if ever a name was well applied, it was so in this instance!

The poultry-yard occupied an area of 200 square yards on the southeast bank of the lake. It was enclosed with a palisade, and within were separate divisions for the proposed inhabitants, and huts of branches divided into compartments awaiting their occupants.

The first was the pair of tinamons, who were not long in breeding numerous little ones. They had for companions half-a-dozen ducks, who were always by the water-side. Some of these belonged to that Chinese variety whose wings open like a fan, and whose plumage rivals in brilliance that of the golden pheasant. Some days later, Herbert caught a pair of magnificent curassows, birds of the gallinaceæ family, with long rounding tails. These soon bred others, and as to the pellicans, the kingfishers, the moorhens, they came of themselves to the poultry-yard. And soon, all this little world, after some disputing, cooing, scolding, clucking, ended by agreeing and multiplying at a rate sufficient for the future wants of the colony.

Smith, in order to complete his work, established a pigeon-house in the corner of the poultry-yard, and placed therein a dozen wild pigeons. These birds readily habituated themselves to their new abode, and returned there each evening, showing a greater propensity to domestication than the wood pigeons, their congeners, which do not breed except in a savage state.

And now the time was come to make use of the envelope in the manufacture of clothing, for to keep it intact in order to attempt to leave the island by risking themselves in a balloon filled with heated air over a sea, which might be called limitless, was only to be thought of by men deprived of all other resources, and Smith, being eminently practical, did not dream of such a thing.

It was necessary to bring the envelope to Granite House, and the colonists busied themselves in making their heavy cart less unwieldly and lighter. But though the vehicle was provided, the motor was still to be found! Did not there exist in the island some ruminant of indiginous species which could replace the horse, ass, ox, or cow? That was the question.

“Indeed,” said Pencroff, “a draught animal would be very useful to us, while we are waiting until Mr. Smith is ready to build a steam-wagon or a locomotive, though doubtless, some day we will have a railway to Balloon Harbor, with a branch road up Mount Franklin!”

And the honest sailor, in talking thus, believed what he said. Such is the power of imagination combined with faith!

But, in truth, an animal capable of being harnessed would have just suited Pencroff, and as Fortune favored him, she did not let him want.

One day, the 23d of December, the colonists, busy at the Chimneys, heard Neb crying and Top barking in such emulation, that dreading some terrible accident, they ran to them.

What did they see? Two large, beautiful animals, which had imprudently ventured upon the plateau, the causeways not having been closed. They seemed like two horses, or rather two asses, male and female, finely shaped, of a light bay color, striped with black on the head, neck, and body, and with white legs and tail. They advanced tranquilly, without showing any fear, and looked calmly on these men in whom they had not yet recognized their masters.

“They are onagers,” cried Herbert. “Quadrupeds of a kind between the zebra and the quagga.”

“Why aren’t they asses?” asked Neb.

“Because they have not long ears, and their forms are more graceful.”

“Asses or horses,” added Pencroff—“they are what Mr. Smith would call “motors,” and it will be well to capture them!”

The sailor, without startling the animals, slid through the grass to the causeway over Glycerine Creek, raised it, and the onagers were prisoners. Should they be taken by violence, and made to submit to a forced domestication? No. It was decided that for some days they would let these animals wander at will over the plateau where the grass was abundant, and a stable was at once constructed near to the poultry-yard in which the onagers would find a good bedding, and a refuge for the night.

The fine pair were thus left entirely at liberty, and the colonists avoided approaching them. In the meantime the onagers often tried to quit the plateau, which was too confined for them, accustomed to wide ranges and deep forests. The colonists saw them following around the belt of water impossible to cross, whinnying and galloping over the grass, and then resting quietly for hours regarding the deep woods from which they were shut off.

In the meantime, harness had been made from vegetable fibres, and some days after the capture of the onagers, not only was the cart ready, but a road, or rather a cut, had been made through the forest all the way from the bend in the Mercy to Balloon Harbor. They could therefore get to this latter place with the cart, and towards the end of the month the onagers were tried for the first time.

Pencroff had already coaxed these animals so that they ate from his hand, and he could approach them without difficulty, but, once harnessed, they reared and kicked, and were with difficulty kept from breaking loose, although it was not long before they submitted to this new service.

This day, every one except Pencroff, who walked beside his team, rode in the cart to Balloon Harbor. They were jolted about a little over this rough road, but the cart did not break down, and they were able to load it, the same day, with the envelope and the appurtenances to the balloon.

By 8 o’clock in the evening, the cart, having recrossed the bridge, followed down the bank of the Mercy and stopped on the beach. The onagers were unharnessed, placed in the stable, and Pencroff, before sleeping, gave a sigh of satisfaction that resounded throughout Granite House.

CHAPTER XXX.CLOTHING—SEAL-SKIN BOOTS—MAKING PYROXYLINE—PLANTING—THE FISH—TURTLES’ EGGS—JUP’S EDUCATION—THE CORRAL-HUNTING MOUFFLONS—OTHER USEFUL ANIMALS AND VEGETABLES—HOME THOUGHTS.

The first week In January was devoted to making clothing. The needles found in the box were plied by strong, if not supple fingers, and what was sewed, was sewed strongly. Thread was plenty, as Smith had thought of using again that with which the strips of the balloon had been fastened together. These long bands had been carefully unripped by Spilett and Herbert with commendable patience, since Pencroff had thrown aside the work, which bothered him beyond measure; but when it came to sewing again the sailor was unequalled.

The varnish was then removed from the cloth by means of soda procured as before, and the cloth was afterwards bleached in the sun. Some dozens of shirts and socks—the latter, of course, not knitted, but made of sewed strips—were thus made. How happy it made the colonists to be clothed again in white linen—linen coarse enough, it is true, but they did not mind that—and to lie between sheets, which transformed the banks of Granite House into real beds! About this time they also made boots from seal leather, which were a timely substitute for those brought from America. They were long and wide enough, and never pinched the feet of the pedestrians.

In the beginning of the year (1866) the hot weather was incessant, but the hunting in the woods, which fairly swarmed with birds and beasts, continued; and Spilett and Herbert were too good shots to waste powder. Smith had recommended them to save their ammunition, and that they might keep it for future use the engineer took measures to replace it by substances easily renewable. How could he tell what the future might have in store for them in case they left the island? It behooved them, therefore, to prepare for all emergencies.

As Smith had not discovered any lead in the island he substituted iron shot, which were easily made. As they were not so heavy as leaden ones they had to be made larger, and the charges contained a less number, but the skill of the hunters counterbalanced this defect. Powder he could have made, since he had all the necessary materials but as its preparation requires extreme care, and as without special apparatus it is difficult to make it of good quality, Smith proposed to manufacture pyroxyline, a kind of gun-cotton, a substance in which cotton is not necessary, except as cellulose. Now cellulose is simply the elementary tissue of vegetables, and is found in almost a pure state not only in cotton, but also in the texile fibres of hemp and flax, in paper and old rags, the pith of the elder, etc. And it happened that elder trees abounded in the island towards the mouth of Red Creek:—the colonists had already used its shoots and berries in place of coffee.

Thus they had the cellulose at hand, and the only other substance necessary for the manufacture of pyroxyline was nitric acid, which Smith could easily produce as before. The engineer, therefore, resolved to make and use this combustible, although he was aware that it had certain serious inconveniences, such as inflaming at 170° instead of 240°, and a too instantaneous deflagration for firearms. On the other hand, pyroxyline had these advantages—it was not affected by dampness, it did not foul the gun-barrels, and its explosive force was four times greater than that of gunpowder.

In order to make the pyroxyline, Smith made a mixture of three parts of nitric acid with five of concentrated sulphuric acid, and steeped the cellulose in this mixture for a quarter of an hour; afterwards it was washed in fresh water and left to dry. The operation succeeded perfectly, and the hunters had at their disposal a substance perfectly prepared, and which, used with discretion, gave excellent results.

About this time the colonists cleared three acres of Prospect Plateau, leaving the rest as pasture for the onagers. Many excursions were made into Jacamar Wood and the Far West, and they brought back a perfect harvest of wild vegetables, spinach, cresses, charlocks, and radishes, which intelligent culture would greatly change, and which would serve to modify the flesh diet which the colonists had been obliged to put up with. They also hauled large quantities of wood and coal, and each excursion helped improve the roads by grinding down its inequalities under the wheels.

The warren always furnished its contingent of rabbits, and as it was situated without Glycerine creek, its occupants could not reach nor damage the new plantations. As to the oyster-bed among the coast rocks, it furnished a daily supply of excellent mollusks. Further, fish from the lake and river were abundant, as Pencroff had made set-lines on which they often caught trout and another very savory fish marked with small yellow spots on a silver-colored body. Thus Neb, who had charge of the culinary department, was able to make an agreeable change in the menu of each repast. Bread alone was wanting at the colonists’ table, and they felt this privation exceedingly.

Sometimes the little party hunted the sea-turtles, which frequented the coast at Mandible Cape. At this season the beach was covered with little mounds enclosing the round eggs, which were left to the sun to hatch; and as each

Comments (0)