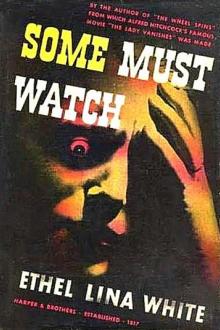

Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White (books for 5 year olds to read themselves .TXT) 📕

- Author: Ethel Lina White

- Performer: -

Book online «Some Must Watch by Ethel Lina White (books for 5 year olds to read themselves .TXT) 📕». Author Ethel Lina White

chair—with drawn face and clay-colored lids—as rigid as a mummy in its

case.

When she lingered in the dressingroom, she heard scuffle and rapid

footsteps, on the other side of the wall.

“She’s got out of bed again,” she thought dully.

If her suspicion were correct, Lady Warren did not lack the strength far

a rapid scramble; for she lay campasedly covered with her old-lady white

fleece, when Helen entered.

“Why did you leave me, girl?” she demanded. “You’re paid to look after

me.”

Helen lacked the spirit to lie.

“I went to telephone,” she said. “But—the line has been blown down. I

couldn’t get through.”

As she spoke, Helen became aware of Lady Warren’s uneasy glances around

the room. The fact that she had power to be an unwelcome obstacle to

some plan, braced her up to came to grips with the old lady.

“Why did you get out of bed?” she asked.

“I didn’t. I can’t. Don’t be a fool.”

“I’m certainly not such a fool as you think. Besides, there is nothing

to hide. You’re not officially paralyzed or bedridden. People have got

the impression that you are helpless—that’s all. Why shouldn’t you get

out of bed if you want to?”

Instead of being furious, Lady Warren pondered the speech.

“Never tell the whole,” she said. “Always keep something up your sleeve

when you’re old, and at the mercy of other people. I like to get about,

when no one’s looking.

“Of course you do,” agreed Helen. “I’ll tell no one, I promise.”

And then her deathless curiosity prompted another question.

“What were you looking for?”

“My charm. It’s a lucky green elephant, with its trunk up. I wanted it,

because I was afraid.”

As Helen looked at her, in surprise, because she thought that age

outlived the emotions, she suddenly remembered the cross which hung

above her bed.

“I’ve something far better than any green elephant,” she said eagerly.

“I’m going to fetch it. And then nothing can hurt you—or me.”

It was not until she was outside the room that she wondered whether Lady

Warren had wanted to send her away. But, even if she had played into

her hands, she did not care, so strong was her wish to hold her Cross.

“I needn’t have been afraid,” she thought. “While I forgot about It, all

the time, it was there—keeping me safe from all evil”

Although the wind was howling in the empty rooms on the second floor,

and anyone might keep step with her, on the back-stairs, while she

mounted the front, she felt raised above fear. Fighting the fierce

pressure of the draught, she snapped on the light in her bedroom.

The first thing she saw was the bare wall above her bed.

The Cross had disappeared.

She caught at the door for support, as the ground seemed to collapse

under her feet. An enemy was inside the house. He had robbed her of the

symbol of protection. Anything might happen to her. Nothing was safe or

sure.

At that moment she felt she had reached the dividingline between sanity

and madness. At any moment a cell might snap in her brain. She felt

poised on the lip of a bottomless drop.

And then her mind suddenly cleared of its mist, and she believed she had

found a solution of the mystery.

The disappearance of the Cross was a trick played on her by Nurse

Barker. The woman was hiding somewhere in the house.

Rushing downstairs, to the lobby, she found that her intuition had

played her false. The front door was still bolted, and the chain in its

place.

“Unless she went out by the back-door, which is most unlikely, she’s

still here,” thought Helen.

Although she was vaguely worried by her loss, the relief was

overwhelming. What she now feared far more than danger outside, was the

threat of peril from within.

The disorder of the bed told her that, in her absence, Lady Warren had

been engaged in her mysterious search. A drawer protruded from a chest,

which stood in an alcove, showing that the old woman had been disturbed

in her labors.

As she was out of sight of the bed, Helen went up to it, and tried to

close it—to be prevented by some object stuffed at the back. Getting

hold of one corner, she managed to pull it. It was a white scarf.

THE WALLS FALL DOWN

Helen turned over the scarf, in fingers which had grown suddenly old. It

was of good-quality silk, machine-knitted, and was quite new. There was

a smear of mud on one side and pine-needles were entangled in the mesh

of its fabric.

Conscious of overwhelming horror in store, she shook it out—revealing a

gap in the fringe, at one end—a jagged, irregular tear, as though it had

been bitten.

With a strange cry, she threw it from her. This was the scarf that

Ceridwen’s teeth had closed over in her death-agony. It was horrible,

unclean. It had encircled the throat of a murderer.

Like a rocket, shooting up through the darkness of her mind, and

breaking into a cluster of stars, a host of questions splashed and

spattered her brain. How did the scarf get inside Lady Warren’s drawer?

Was she hiding it? What connection had she with the crime? Or had

someone else put it there? Was the murderer actually inside the house?

At the thought, she felt already dead. Every cell seemed atrophied,

every fibre withered. She stood locked in temporary paralysis,

muscle-bound, with rigid spine, and blasted faculties.

Yet while she could not see the room, or hear the sound of the wind, or

feel the table under her fingers, she seemed to be looking inwards at a

mental picture.

The Summit was breaking up. The walls had cracked in every direction.

Those thin lines, like the veining of a flash of lightning, were

splintering into fissures. All around her was a tearing and a rending,

as the branches widened, leaving her defenseless to the night.

Suddenly she heard the sound of a sob, and realized that it was her own

voice. In the glass she saw a girl’s face—pinched and pallid—staring at

her, from dilated eyes, black with fear. By the aureole of crisping

light-red hair, she knew that girl was herself.

At the sight, a memory stirred in her mind.

“‘Ginger for pluck’,” she whispered.

She was lying down, waiting for the attack, instead of standing, with

her back to the wall. Nerving herself to examine the scarf, she noticed

that it was only slightly damp.

“It would have been soaked, if it had been lying out in the rain,” she

thought. “It must have been brought inside directly after the murder.”

The deduction opened up fresh avenues of horror. No one knew the exact

time when Ceridwen was strangled, except that it was round about

twilight. As everyone—except Oates—was at the Summit, any person could

have slipped outside, for a few minutes, unnoticed. From the Professor

downwards, all were under suspicion.

Dr. Parry had warned her that the crime might have been committed by

someone she knew and trusted. The Professor worked at high mental

pressure, while both his son and Rice were periodically moody. Even Dr.

Parry had the same opportunities, and he had visited the blue room.

This wholesale suspicion might even include old Lady Warren. Miss Warren

had dozed in her chair, that evening, at twilight. How had she used her

half-hour of liberty?

“I’m mad,” thought Helen. “It can’t be everybody. It’s nobody here. It’s

someone, who got in, from outside.”

She shuddered, because, at the back of her mind, persisted that horrible

memory of an open window.

“Girl,” called Lady Warren, “what are you doing there?”

“Getting you a clean handkerchief.”

Helen was astonished by the coolness of her voice. Under the influence

of fear, she seemed to be a dual personality. A self-possessed stranger

had taken command and was carrying on for her, while the real Helen was

staked amid the ruins of the shattered fortress—bait for a human tiger.

“Have you found—anything?” asked Lady Warren.

Helen purposely misunderstood her.

“Yes, a pile,” she said, as she hurriedly replaced the scarf. With a

handkerchief in her hand, she approached the bed.

Lady Warren snatched it from her, and threw it on the floor.

“Girl,” she whispered hoarsely, “I want you to do something.”

“Yes. What is it?”

“Get under the bed.”

Helen’s eyes fell on the ebony stick, by the bed, with a flash of

understanding. The old woman was wandering again, and she wanted to play

her favorite game of stalking housemaids.

“When I crawl out, will you crack me over the head?” she asked.

“You mustn’t come out. You must hide.”

The new Helen, who had taken command, thought she grasped the

significance of this move. It was a ruse to hold her in such a position

that she could see practically nothing of the room.

“It’s too dusty under the bed,” she objected, as she moved cautiously

towards the door.

She had realized the importance of the scarf, as evidence. The Police

should have it in their possession, without delay. She could not

telephone to them, because of the damage—accidental, or otherwise—to

the line; but she could run over to Captain Bean’s cottage, and ask him

to take the necessary steps.

Lady Warren began to whimper, like a terrified child.

“Don’t leave me, girl. The nurse will come. She’s only waiting for you

to go.”

Helen hesitated, although she remembered that, in their last encounter,

Lady Warren had triumphed. Yet the balance of power did not remain

equal, even in a jungle fight; today it might be the tiger’s turn, but,

tomorrow, the lion’s.

She had not yet solved the mystery of Nurse Barker’s disappearance. If

she were actually hiding in the house, she might take her revenge.

“I wish I knew the right thing to do,” she thought.

“If you leave me,” threatened Lady Warren, “I’ll scream. And then, he’ll

come.”

Like the flash of a fer-de-lance, Helen whipped round.

“He?” she asked. “Who?”

“I said, ‘She’ll come’.”

It was obvious that Lady Warren realized her slip, for she bit her lip

and glowered at Helen, like an angry idol.

Helen felt as though she was trying to find the path which threaded a

maze. The old woman knew something which she would not reveal.

It was curious how she remained shackled by ordinary conventions and

considerations, even while one-half of her was pulped with elementary

terror. But, throughout the evening, no single event had been abnormal,

so that, unconsciously, she responded to the laws of civilized life.

The actual murder had taken place outside the Summit, which reduced it

to the level of a newspaper paragraph. The maniac was a kind of

legendary figure, invented by the Press. The most shocking occurrence

was the fact that the housekeeper had got drunk. It was true that both

Nurse Barker and Lady Warren were most unpleasant types; but, in the

course of her experience, Helen had met others who were even more

peculiar. She knew that her own fear was responsible for the grotesque

fancies and suspicions, which shifted through her mind.

Tomorrow would come. She held on to that. She reminded herself that she

had a new job to hold down. If she failed, at a pinch she might find

herself out of

Comments (0)