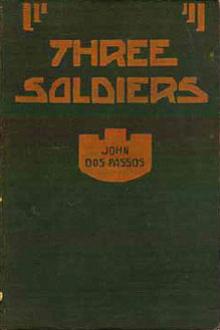

Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (books to read to be successful txt) 📕

- Author: John Dos Passos

- Performer: -

Book online «Three Soldiers by John Dos Passos (books to read to be successful txt) 📕». Author John Dos Passos

Andrews stared for a long while at the line of shields that supported the dark ceiling beams on the wall opposite his cot. The emblems had been erased and the grey stone figures that crowded under the shields,—the satyr with his shaggy goat’s legs, the townsman with his square hat, the warrior with the sword between his legs,—had been clipped and scratched long ago in other wars. In the strong afternoon light they were so dilapidated he could hardly make them out. He wondered how they had seemed so vivid to him when he had lain in his cot, comforted by their comradeship, while his healing wounds itched and tingled. Still he glanced tenderly at the grey stone figures as he left the ward.

Downstairs in the office where the atmosphere was stuffy with a smell of varnish and dusty papers and cigarette smoke, he waited a long time, shifting his weight restlessly from one foot to the other.

“What do you want?” said a red-haired sergeant, without looking up from the pile of papers on his desk.

“Waiting for travel orders.”

“Aren’t you the guy I told to come back at three?”

“It is three.”

“H’m!” The sergeant kept his eyes fixed on the papers, which rustled as he moved them from one pile to another. In the end of the room a typewriter clicked slowly and jerkily. Andrews could see the dark back of a head between bored shoulders in a woolen shirt leaning over the machine. Beside the cylindrical black stove against the wall a man with large mustaches and the complicated stripes of a hospital sergeant was reading a novel in a red cover. After a long silence the red-headed sergeant looked up from his papers and said suddenly:

“Ted.”

The man at the typewriter turned slowly round, showing a large red face and blue eyes.

“We-ell,” he drawled.

“Go in an’ see if the loot has signed them papers yet.”

The man got up, stretched himself deliberately, and slouched out through a door beside the stove. The red-haired sergeant leaned back in his swivel chair and lit a cigarette.

“Hell,” he said, yawning.

The man with the mustache beside the stove let the book slip from his knees to the floor, and yawned too.

“This goddam armistice sure does take the ambition out of a feller,” he said.

“Hell of a note,” said the red-haired sergeant. “D’you know that they had my name in for an O.T.C.? Hell of a note goin’ home without a Sam Browne.”

The other man came back and sank down into his chair in front of the typewriter again. The slow, jerky clicking recommenced.

Andrews made a scraping noise with his foot on the ground.

“Well, what about that travel order?” said the red-haired sergeant.

“Loot’s out,” said the other man, still typewriting.

“Well, didn’t he leave it on his desk?” shouted the red-haired sergeant angrily.

“Couldn’t find it.”

“I suppose I’ve got to go look for it…. God!” The red-haired sergeant stamped out of the room. A moment later he came back with a bunch of papers in his hand.

“Your name Jones?” he snapped to Andrews.

“No.”

“Snivisky?”

“No…. Andrews, John.”

“Why the hell couldn’t you say so?”

The man with the mustaches beside the stove got to his feet suddenly. An alert, smiling expression came over his face.

“Good afternoon, Captain Higginsworth,” he said cheerfully.

An oval man with a cigar slanting out of his broad mouth came into the room. When he talked the cigar wobbled in his mouth. He wore greenish kid gloves, very tight for his large hands, and his puttees shone with a dark lustre like mahogany.

The red-haired sergeant turned round and half-saluted.

“Goin’ to another swell party, Captain?” he asked.

The Captain grinned.

“Say, have you boys got any Red Cross cigarettes? I ain’t only got cigars, an’ you can’t hand a cigar to a lady, can you?” The Captain grinned again. An appreciative giggle went round.

“Will a couple of packages do you? Because I’ve got some here,” said the red-haired sergeant reaching in the drawer of his desk.

“Fine.” The captain slipped them into his pocket and swaggered out doing up the buttons of his buff-colored coat.

The sergeant settled himself at his desk again with an important smile.

“Did you find the travel order?” asked Andrews timidly. “I’m supposed to take the train at four-two.”

“Can’t make it…. Did you say your name was Anderson?”

“Andrews…. John Andrews.”

“Here it is…. Why didn’t you come earlier?”

The sharp air of the ruddy winter evening, sparkling in John Andrews’s nostrils, vastly refreshing after the stale odors of the hospital, gave him a sense of liberation. Walking with rapid steps through the grey streets of the town, where in windows lamps already glowed orange, he kept telling himself that another epoch was closed. It was with relief that he felt that he would never see the hospital again or any of the people in it. He thought of Chrisfield. It was weeks and weeks since Chrisfield had come to his mind at all. Now it was with a sudden clench of affection that the Indiana boy’s face rose up before him. An oval, heavily-tanned face with a little of childish roundness about it yet, with black eyebrows and long black eyelashes. But he did not even know if Chrisfield were still alive. Furious joy took possession of him. He, John Andrews, was alive; what did it matter if everyone he knew died? There were jollier companions than ever he had known, to be found in the world, cleverer people to talk to, more vigorous people to learn from. The cold air circulated through his nose and lungs; his arms felt strong and supple; he could feel the muscles of his legs stretch and contract as he walked, while his feet beat jauntily on the irregular cobblestones of the street. The waiting room at the station was cold and stuffy, full of a smell of breathed air and unclean uniforms. French soldiers wrapped in their long blue coats, slept on the benches or stood about in groups, eating bread and drinking from their canteens. A gas lamp in the center gave dingy light. Andrews settled himself in a corner with despairing resignation. He had five hours to wait for a train, and already his legs ached and he had a side feeling of exhaustion. The exhilaration of leaving the hospital and walking free through wine-tinted streets in the sparkling evening air gave way gradually to despair. His life would continue to be this slavery of unclean bodies packed together in places where the air had been breathed over and over, cogs in the great slow-moving Juggernaut of armies. What did it matter if the fighting had stopped? The armies would go on grinding out lives with lives, crushing flesh with flesh. Would he ever again stand free and solitary to live out joyous hours which would make up for all the boredom of the treadmill? He had no hope. His life would continue like this dingy, ill-smelling waiting room where men in uniform slept in the fetid air until they should be ordered-out to march or to stand in motionless rows, endlessly, futilely, like toy soldiers a child has forgotten in an attic.

Andrews got up suddenly and went out on the empty platform. A cold wind blew. Somewhere out in the freight yards an engine puffed loudly, and clouds of white steam drifted through the faintly lighted station. He was walking up and down with his chin sunk into his coat and his hands in his pockets, when somebody ran into him.

“Damn,” said a voice, and the figure darted through a grimy glass door that bore the sign: “Buvette.” Andrews followed absent-mindedly.

“I’m sorry I ran into you…. I thought you were an M.P., that’s why I beat it.” When he spoke, the man, an American private, turned and looked searchingly in Andrews’s face. He had very red cheeks and an impudent little brown mustache. He spoke slowly with a faint Bostonian drawl.

“That’s nothing,” said Andrews.

“Let’s have a drink,” said the other man. “I’m A.W.O.L. Where are you going?”

“To some place near Bar-le-Duc, back to my Division. Been in hospital.”

“Long?”

“Since October.”

“Gee…. Have some Curacoa. It’ll do you good. You look pale…. My name’s Henslowe. Ambulance with the French Army.”

They sat down at an unwashed marble table where the soot from the trains made a pattern sticking to the rings left by wine and liqueur glasses.

“I’m going to Paris,” said Henslowe. “My leave expired three days ago. I’m going to Paris and get taken ill with peritonitis or double pneumonia, or maybe I’ll have a cardiac lesion…. The army’s a bore.”

“Hospital isn’t any better,” said Andrews with a sigh. “Though I shall never forget the night with which I realized I was wounded and out of it. I thought I was bad enough to be sent home.”

“Why, I wouldn’t have missed a minute of the war…. But now that it’s over…Hell! Travel is the password now. I’ve just had two weeks in the Pyrenees. Nimes, Arles, Les Baux, Carcassonne, Perpignan, Lourdes, Gavarnie, Toulouse! What do you think of that for a trip?… What were you in?”

“Infantry.”

“Must have been hell.”

“Been! It is.”

“Why don’t you come to Paris with me?”

“I don’t want to be picked up,” stammered Andrews.

“Not a chance…. I know the ropes…. All you have to do is keep away from the Olympia and the railway stations, walk fast and keep your shoes shined…and you’ve got wits, haven’t you?”

“Not many…. Let’s drink a bottle of wine. Isn’t there anything to eat to be got here?”

“Not a damn thing, and I daren’t go out of the station on account of the M.P. at the gate…. There’ll be a diner on the Marseilles express.”

“But I can’t go to Paris.”

“Sure…. Look, how do you call yourself?”

“John Andrews.”

“Well, John Andrews, all I can say is that you’ve let ‘em get your goat. Don’t give in. Have a good time, in spite of ‘em. To hell with ‘em.” He brought the bottle down so hard on the table that it broke and the purple wine flowed over the dirty marble and dripped gleaming on the floor.

Some French soldiers who stood in a group round the bar turned round.

“V’la un gars qui gaspille le bon vin,” said a tall red-faced man, with long sloping whiskers.

“Pour vingt sous j’mangerai la bouteille,” cried a little man lurching forward and leaning drunkenly over the table.

“Done,” said Henslowe. “Say, Andrews, he says he’ll eat the bottle for a franc.”

He placed a shining silver franc on the table beside the remnants of the broken bottle. The man seized the neck of the bottle in a black, claw-like hand and gave it a preparatory flourish. He was a cadaverous little man, incredibly dirty, with mustaches and beard of a moth-eaten tow-color, and a purple flush on his cheeks. His uniform was clotted with mud. When the others crowded round him and tried to dissuade him, he said: “M’en fous, c’est mon metier,” and rolled his eyes so that the whites flashed in the dim light like the eyes of dead codfish.

“Why, he’s really going to do it,” cried Henslowe.

The man’s teeth flashed and crunched down on the jagged edge of the glass. There was a terrific crackling noise. He flourished the bottle-end again.

“My God, he’s eating it,” cried Henslowe, roaring with laughter, “and you’re afraid to go to Paris.”

An engine rumbled into the station, with a great hiss of escaping steam.

“Gee, that’s the Paris train! Tiens!” He pressed the franc into the man’s dirt-crusted hand.

“Come along, Andrews.”

As they left the buvette they heard again the crunching crackling noise as the man bit another piece off

Comments (0)