All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕

- Author: William H. Ukers

- Performer: -

Book online «All About Coffee by William H. Ukers (best new books to read .TXT) 📕». Author William H. Ukers

Let us take Englishmen and Dutchmen first. In Danvers's Letters (1611) we have both "coho pots" and "coffao pots"; Sir T. Roe (1615) and Terry (1616) have cohu; Sir T. Herbert (1638) has coho and copha; Evelyn (1637), coffee; Fryer (1673) coho; Ovington (1690), coffee; and Valentijn (1726), coffi. And from the two examples given by Col. Prideaux, we see that Jourdain (1609) has cohoo, and Revett (1609) has coffe.

To the above should be added the following by English writers, given in Foster's English Factories in India (1618–21, 1622–23, 1624–29): cowha (1619), cowhe, couha (1621), coffa (1628).

Let us now see what foreigners (chiefly French and Italian) write. The earliest European mention is by Rauwolf, who knew it in Aleppo in 1573. He has the form chaube. Prospero Alpini (1580) has caova; Paludanus (1598) chaoua; Pyrard de Laval (1610) cahoa; P. Della Valle (1615) cahue; Jac. Bontius (1631) caveah; and the Journal d'Antoine Galland (1673) cave. That is, Englishmen use forms of a certain distinct type, viz., cohu, coho, coffao, coffe, copha, coffee, which differ from the more correct transliteration of foreigners.

In 1610 the Portuguese Jew, Pedro Teixeira (in the Hakluyt Society's edition of his Travels) used the word kavàh.

The inferences from these transitional forms seem to be: 1. The word found its way into the languages of Europe both from the Turkish and from the Arabic. 2. The English forms (which have strong stress on the first syllable) have ŏ instead of ă, and f instead of h. 3. The foreign forms are unstressed and have no h. The original v or w (or labialized u) is retained or changed into f.

It may be stated, accordingly, that the chief reason for the existence of two distinct types of spelling is the omission of h in unstressed languages, and the conversion of h into f under strong stress in stressed languages. Such conversion often takes place in Turkish; for example, silah dar in Persian (which is a highly stressed language) becomes zilif dar in Turkish. In the languages of India, on the other hand, in spite of the fact that the aspirate is usually very clearly sounded, the word qăhvăh is pronounced kaiva by the less educated classes, owing to the syllables being equally stressed.

Now for the French viewpoint. Jardin[3] opines that, as regards the etymology of the word coffee, scholars are not agreed and perhaps never will be. Dufour[4] says the word is derived from caouhe, a name given by the Turks to the beverage prepared from the seed. Chevalier d'Arvieux, French consul at Alet, Savary, and Trevoux, in his dictionary, think that coffee comes from the Arabic, but from the word cahoueh or quaweh, meaning to give vigor or strength, because, says d'Arvieux, its most general effect is to fortify and strengthen. Tavernier combats this opinion. Moseley attributes the origin of the word coffee to Kaffa. Sylvestre de Sacy, in his Chréstomathie Arabe, published in 1806, thinks that the word kahwa, synonymous with makli, roasted in a stove, might very well be the etymology of the word coffee. D'Alembert in his encyclopedic dictionary, writes the word caffé. Jardin concludes that whatever there may be in these various etymologies, it remains a fact that the word coffee comes from an Arabian word, whether it be kahua, kahoueh, kaffa or kahwa, and that the peoples who have adopted the drink have all modified the Arabian word to suit their pronunciation. This is shown by giving the word as written in various modern languages:

French, café; Breton, kafe; German, kaffee (coffee tree, kaffeebaum); Dutch, koffie (coffee tree, koffieboonen); Danish, kaffe; Finnish, kahvi; Hungarian, kavé; Bohemian, kava; Polish, kawa; Roumanian, cafea; Croatian, kafa; Servian, kava; Russian, kophe; Swedish, kaffe; Spanish, café; Basque, kaffia; Italian, caffè; Portuguese, café; Latin (scientific), coffea; Turkish, kahué; Greek, kaféo; Arabic, qahwah (coffee berry, bun); Persian, qéhvé (coffee berry, bun[5]); Annamite, ca-phé; Cambodian, kafé; Dukni[6], bunbund[7]; Teluyan[8], kapri-vittulu; Tamil[9], kapi-kottai or kopi; Canareze[10], kapi-bija; Chinese, kia-fey, teoutsé; Japanese, kéhi; Malayan, kawa, koppi; Abyssinian, bonn[11]; Foulak, legal café[12]; Sousou, houri caff[13]; Marquesan, kapi; Chinook[14], kaufee; Volapuk, kaf; Esperanto, kafva.

A brief account of the cultivation of the coffee plant in the Old World and its introduction into the New—A romantic coffee adventure

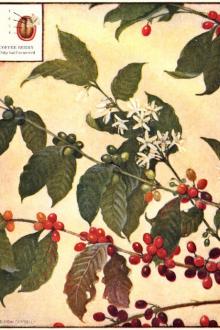

The history of the propagation of the coffee plant is closely interwoven with that of the early history of coffee drinking, but for the purposes of this chapter we shall consider only the story of the inception and growth of the cultivation of the coffee tree, or shrub, bearing the seeds, or berries, from which the drink, coffee, is made.

Careful research discloses that most authorities agree that the coffee plant is indigenous to Abyssinia, and probably Arabia, whence its cultivation spread throughout the tropics. The first reliable mention of the properties and uses of the plant is by an Arabian physician toward the close of the ninth century A.D., and it is reasonable to suppose that before that time the plant was found growing wild in Abyssinia and perhaps in Arabia. If it be true, as Ludolphus writes,[15] that the Abyssinians came out of Arabia into Ethiopia in the early ages, it is possible that they may have brought the coffee tree with them; but the Arabians must still be given the credit for discovering and promoting the use of the beverage, and also for promoting the propagation of the plant, even if they found it in Abyssinia and brought it to Yemen.

Some authorities believe that the first cultivation of coffee in Yemen dates back to 575 A.D., when the Persian invasion put an end to the Ethiopian rule of the negus Caleb, who conquered the country in 525.

Certainly the discovery of the beverage resulted in the cultivation of the plant in Abyssinia and in Arabia; but its progress was slow until the 15th and 16th centuries, when it appears as intensively carried on in the Yemen district of Arabia. The Arabians were jealous of their new found and lucrative industry, and for a time successfully prevented its spread to other countries by not permitting any of the precious berries to leave the country unless they had first been steeped in boiling water or parched, so as to destroy their powers of germination. It may be that many of the early failures successfully to introduce the cultivation of the coffee plant into other lands was also due to the fact, discovered later, that the seeds soon lose their germinating power.

However, it was not possible to watch every avenue of transport, with thousands of pilgrims journeying to and from Mecca every year; and so there would appear to be some reason to credit the Indian tradition concerning the introduction of coffee cultivation into southern India by Baba Budan, a Moslem pilgrim, as early as 1600, although a better authority gives the date as 1695. Indian tradition relates that Baba Budan planted his seeds near the hut he built for himself at Chickmaglur in the mountains of Mysore, where, only a few years since, the writer found the descendants of these first plants growing under the shade of the centuries-old original jungle trees. The greater part of the plants cultivated by the natives of Kurg and Mysore appear to have come from the Baba Budan importation. It was not until 1840 that the English began the cultivation of coffee in India. The plantations extend now from the extreme north of Mysore to Tuticorin.

Early Cultivation by the Dutch

In the latter part of the 16th century, German, Italian, and Dutch botanists and travelers brought back from the Levant considerable information regarding the new plant and the beverage. In 1614 enterprising Dutch traders began to examine into the possibilities of coffee cultivation and coffee trading. In 1616 a coffee plant was successfully transported from Mocha to Holland. In 1658 the Dutch started the cultivation of coffee in Ceylon, although the Arabs are said to have brought the plant to the island prior to 1505. In 1670 an attempt was made to cultivate coffee on European soil at Dijon, France, but the result was a failure.

In 1696, at the instigation of Nicolaas Witsen, then burgomaster of Amsterdam, Adrian Van Ommen, commander at Malabar, India, caused to be shipped from Kananur, Malabar, to Java, the first coffee plants introduced into that island. They were grown from seed of the Coffea arabica brought to Malabar from Arabia. They were planted by Governor-General Willem Van Outshoorn on the Kedawoeng estate near Batavia, but were subsequently lost by earthquake and flood. In 1699 Henricus Zwaardecroon imported some slips, or cuttings, of coffee trees from Malabar into Java. These were more successful, and became the progenitors of all the coffees of the Dutch East Indies. The Dutch were then taking the lead in the propagation of the coffee plant.

In 1706 the first samples of Java coffee, and a coffee plant grown in Java, were received at the Amsterdam botanical gardens. Many plants were afterward propagated from the seeds produced in the Amsterdam gardens, and these were distributed to some of the best known botanical gardens and private conservatories in Europe.

While the Dutch were extending the cultivation of the plant to Sumatra, the Celebes, Timor, Bali, and other islands of the Netherlands Indies, the French were seeking to introduce coffee cultivation into their colonies. Several attempts were made to transfer young plants from the Amsterdam botanical gardens to the botanical gardens at Paris; but all were failures.

In 1714, however, as a result of negotiations entered into between the French government and the municipality of Amsterdam, a young and vigorous plant about five feet tall was sent to Louis XIV at the chateau of Marly by the burgomaster of Amsterdam. The day following, it was transferred to the Jardin des Plantes at Paris, where it was received with appropriate ceremonies by Antoine de Jussieu, professor of botany in charge. This tree was destined to be the progenitor of most of the coffees of the French colonies, as well as of those of South America, Central America, and Mexico.

The Romance of Captain Gabriel de Clieu

Two unsuccessful attempts were made to transport to the Antilles plants grown from the seed of the tree presented to Louis XIV; but the honor of eventual success was won by a young Norman gentleman, Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, a naval officer, serving at the time as captain of infantry at Martinique. The story of de Clieu's achievement is the most romantic chapter in the history of the propagation of the coffee plant.

His personal affairs calling him to France, de Clieu conceived the idea of utilizing the return voyage to introduce coffee cultivation into Martinique. His first difficulty lay in obtaining several of the plants then being cultivated in Paris, a difficulty at last overcome through the instrumentality of M. de Chirac, royal physician, or, according to a letter written by de Clieu himself, through the kindly offices of a lady of quality to whom de Chirac could give no refusal. The plants selected

Comments (0)