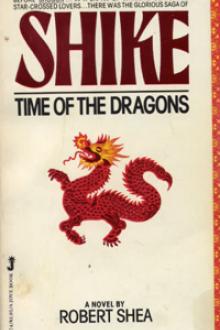

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

Sametono had little to say until the generals were finished outlining their plans for meeting the new threat. Then he raised his young voice. His hands, as he gestured, were trembling.

“Honoured generals and brave officers, today and the next few days will decide the fate of the Sunrise Land. Until now I have stayed out of battle, persuaded that the life of the Shogun should not be risked. But if we lose now, it does not matter whether the Shogun lives or dies. Today, I go into battle. I ask you generals to assign me a place in the defences.”

There were cheers from many of the officers. Jebu himself was stirred. He did not want to frustrate the boy, but he had promised Taniko he would do everything in his power to keep Sametono out of combat, and there was good reason for doing so besides Taniko’s maternal fears. The death of Sametono would be a disaster from which the forces of the Sunrise Land might never recover. Jebu asked for permission to speak.

“I have fought in many battles, honoured generals,” he said. “I ask you to imagine what it would do to our warriors, brave as they are, to hear in this moment of crisis that the Shogun himself has been killed in battle. Precisely because it will be so difficult to hold back the enemy now that they have three times as many troops as before, it is all the more important that nothing happen to our Shogun. I beg his lordship to spare us any fear for his safety, and I beg you honoured generals to intercede with him not to expose his exalted person to danger.”

There was a muttering of agreement as Jebu sat down. Dawn was starting to break over Hakata Bay. Looking down the beach, Jebu could see mass pyres where stacked enemy corpses were being burned by slaves. The dead samurai had been taken inland for more ceremonious cremation. Wrecked Mongol siege machines were being chopped apart by labourers so the wood could be re-used. Here and there beached ships were being salvaged. The hulks of enemy junks sunk in the offing were left there as a barrier to other landings. Out on the bay many of the invaders’ sails were up and their ships were beginning to move towards shore. Shrill voices could be heard shouting war cries across the water, and the drums on the ships were taking up their inexorable beat. Jebu turned his attention back to the generals. Sametono was glaring at him as if he wanted to kill him.

Miura Zumiyoshi, the senior officer among the generals, addressed Sametono. “Your Lordship, we think the Zinja monk has spoken well.

To lose you might be the very blow that would weaken our men’s morale enough to let the Mongols break through our lines. We humbly suggest that you refrain from going into combat.”

Sametono’s face turned a deep red. He was the Supreme Commander of these generals, of all samurai in the Sunrise Land. But leadership in the Sacred Islands was traditionally never a matter of one man’s will. Leaders who disregarded the opinions of their supporters soon lost that support. Sametono knew that Jebu had turned the consensus against him. He nodded abruptly and uttered his acceptance of the generals’ “suggestion” in a low voice.

Shortly afterwards the meeting ended. Jebu felt a tug at his sleeve and turned to see Moko’s son Sakagura smiling and bowing to him. The young man looked thin and wolfish after two months of leading forays against the Mongols nearly every night.

“Master Jebu,” he said, “I wish to ask a favour. I have never had an opportunity to meet his lordship. Would you introduce me now, while he is here?”

“I don’t think the honoured Shogun wishes to speak with me just now,” said Jebu.

“Shik��, I may die today. I may never have another chance.” As he called Jebu by the title Moko always used, Sakagura looked so much like his father that Jebu decided to help him. Motioning Sakagura to follow him, he approached Sametono, who was striding angrily and silently through rows of bowing officers.

“Excuse me, your lordship,” Jebu said. “May I introduce Captain Hayama Sakagura? It is Captain Sakagura who plans and leads the kobaya night attacks which have been so effective.”

Sametono stared angrily at Jebu, as if about to reprimand him for daring to speak to him. But his expression changed when he turned to Sakagura. The young men were ten years apart in age and both of the same height. Jebu towered over them. Sakagura bowed deeply to the Shogun.

“Your father is an old friend of my family, captain,” said Sametono with a smile. “Your exploits are marvellous. How many heads of Mongol generals have you brought back?”

“Seventeen, your lordship,” said Sakagura, baring his teeth with pleasure.

When Sakagura retold his adventures, any Mongol officer whose head he took was posthumously promoted to the rank of general, Jebu thought.

“I am proud to meet you,” Sametono said solemnly. “Just to man an oar in one of your kobaya would be a privilege.”

Sakagura bowed, then beckoned to a servant whom Jebu had not noticed before, who handed him a bag made of shiny crimson silk. With a low bow Sakagura offered it to Sametono. “May I present your lordship with a small token of my esteem?”

Sametono opened the bag with curiosity and drew out a wooden statue of a shaven-headed seated figure holding a disk-shaped gumbai, a kind of war fan carried by generals, in one hand and a Buddhist rosary in the other. The delicate carving clearly delineated a stern, unyielding face. The pose was traditional, but the vigour in the small teakwood statue could only have come from the hand of a talented artist. The fan identified the figure as Hachiman, god of war, patron of the Muratomo. The statue had been left unpainted, the sculptor having the good taste to realize that the warm tones of the natural wood were sufficient adornment.

“There is much life force in this,” said Sametono. “I am most grateful to you. By whom was it carved?”

Sakagura bowed. “My unworthy self, your lordship.”

“Not only are you a great captain of ships, you are a remarkable sculptor as well.”

“I inherit my small skill from my father, who was a carpenter, you’ll remember, before your lordship graciously elevated him to the samurai.”

“Your father builds the ships and you shed glory on your samurai family name by the way you captain them,” said Sametono. “Now, I thank you for your gift, and I would like to have a few words with this Zinja monk in private.” Jebu sensed suppressed anger in Sametono’s voice. Sakagura bowed himself out of the Shogun’s presence. Sametono gently put the statue of Hachiman back in its bag and handed it to one of his men standing near by. Then, as if possessed by the war god, he turned a face dark with fury towards Jebu.

“I can never forgive you for what you did today, Master Jebu. Meeting Sakagura only reminds me what heroic feats other young men accomplish, while I remain no more able to do anything than that wooden statue.”

Jebu knelt before Sametono. He felt he could not conduct an argument with the Shogun while looking down at him.

“May I suggest that there is a lesson in that seated statue, your lordship. Our highest symbols of religion and the nation are not expected to plunge into the thick of battle.”

Sametono was obviously close to tears. “I am not a statue. I am a human being who wants to fight to save my country’s life. The generals will not let me plan strategy and they will not let me go into battle. There is nothing I can do.”

“You may not fight where and how you want,” said Jebu gently, sitting back on his heels and looking up at Sametono. “No one can. A nation whose fighting men did not obey orders would lose in any war. Do you suppose that there is one warrior, the Shogun, who is exempt? You must do the duty appropriate to your station, as everyone else must. Eisen and your mother tell me you were unusually enlightened as a child. But one does not light a lamp once and have it stay lit for all time. You must keep fuelling it. Do you understand what I am saying?”

“I understand that you can preach at me like any other monk,” said Sametono, staring at Jebu with hostile eyes. “But you are not like any other monk. You worship neither gods nor Buddhas. What are you but an adventurer in monk’s robes? You’re my mother’s lover, and you carry messages from her to the generals. Yes, I see very well that you want to keep me helpless, like a wooden statue that you can place wherever you wish. You killed my grandfather, and you were involved in the killings of my father and my foster father. And yet my mother lies with you. What kind of power is it that you have over my mother? It is becoming a national scandal that the Shogun’s mother goes to bed with a warrior monk in whose veins flows the blood of our enemies. You and I are both fortunate that I am under obligation to you for saving my life. It is said that a man may not live under the same heaven with the slayer of his father.”

Jebu held out a hand pleadingly. “Sametono. I understand what you are going through.”

“Address me properly.”

“Your lordship. I have felt hatred. I have wanted revenge. I have been torn by the urge to fight and kill when it was my duty to refrain. I beg of you, do not lose what you have always possessed. Do not let your mind be clouded by the passions this war has stirred up.”

“It is you who have clouded my mother’s mind. Stay far from me. I do not wish to see you. You are dismissed.”

Jebu knew that if he spoke another word Sametono would draw the sword Higekiri that hung at his belt. He stood up reluctantly, bowed deeply and backed away. Sametono turned on his heel and walked stiffly to his horse, followed by the retainer carrying Sakagura’s statue. As he watched Sametono go, Jebu discovered that he was crying. Until now there had been a love, almost like father and son, between himself and Sametono. He wept for the loss of that love. And even more for the boy’s loss of enlightenment.

Jebu kicked his horse into a gallop. It raced up the stone ramp to the top of the wall. The thousands of Mongol ships that dotted the bay were moving steadily shorewards under an iron-grey sky. Behind Jebu the rest of his fifty cavalrymen topped the wall. They were all carrying short Zinja bows and wearing armour with black laces. To themselves they were known as the Former Zinja. Together they charged down a removable wooden ramp on the seaward side of the wall.

A three-masted junk with staring eyes painted on the bow had pulled in so close to shore, its flat bottom was nearly scraping the beach.

Chinese infantrymen by the hundreds, armed with murderous pikes, were leaping from the deck of the junk and splashing up the beach. They wore light armour constructed of metal scales adorned with red and green capes and helmet scarves. Their iron shields were painted with fierce beasts-dragons, tigers, eagles. They were larger

Comments (0)