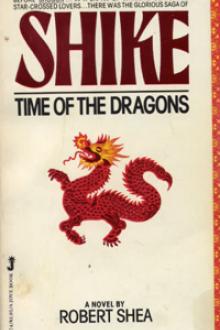

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

The Eormer Zinja stood up in their saddles Mongol-fashion, firing arrows into the Chinese squares. The pikemen in the front ranks were falling, slowing the advance of the invaders. The Eormer Zinja rode into the midst of the pikemen, forcing openings with the weight of their horses and the bite of their swords. A huge man with long black moustaches thrust at Jebu with a pike. Jebu fired an arrow into the man’s face. It crashed into his head just at the bridge of the nose. The pointed steel head of the man’s pike grazed Jebu’s leg, stabbing into his saddle. Another spear hit Jebu’s arm and was deflected by his armoured sleeve. Jebu turned and jerked the pike out of the infantryman’s hands and hit him in the chest with the butt end. The man fell, and Jebu rode his horse over him.

Something struck him on the back of the head like a club and knocked him stunned from his horse. Eor a moment he lay deafened and blinded. He forced himself to stand, and the reek of the Chinese fire powder filled his nostrils, and the screams of his horse tore at his ears. The animal was lying on its side, legs flailing, the left front leg a stump. Jebu killed the horse with a quick thrust of his short Zinja sword through the eye into the brain. Crouching behind the horse Jebu looked around. Near him were dead men, Eormer Zinja and Chinese, and dead horses. Beyond the range of the hua pao blast, Zinja riders were circling and Chinese infantrymen were falling into attack formation.

Jebu started running for the wall, a few of his comrades on foot following him. The men on horseback moved in behind them to cover their retreat and shoot at the Chinese. The wall looked much further away now that Jebu was on foot, and his legs ached as he ran as hard as he could through the sand. He reached gratefully for the rope ladder the samurai on the wall threw down to him, and pulled himself up as a dart from a ship-based Mongol crossbow smashed stone fragments from the wall beside him. On top of the wall he crouched behind the battlements. More platoons of Chinese were wading ashore. Those of his contingent who were still mounted were riding back and forth below the wall, raining arrows on the invaders.

It was typical of the Mongols to fire their hua pao into their own Chinese troops, just to kill a few of their enemy. They were using the Chinese soldiers much as they had the civilians at Kweilin, as a kind of expendable advance screen. The Chinese were courageous and skilled fighters, but they could not have any heart for this war. Only a few years ago they themselves had been fighting against the Mongols. Now even the highest ranking Chinese were treated like slaves. Erom invaders captured the day before, the samurai learned that as soon as the South of the Yang-Tze Eleet had arrived, Arghun had sent for the Chinese admiral and had him beheaded on the deck of Red Tiger as punishment for having taken so long to get there. Arghun had put his old second-in-command, Torluk, now also a tarkhan, in command of the Chinese ships and army. Though the Chinese might not want to fight, their arrival could be enough to defeat the samurai. They brought not only a hundred thousand men, but tens of thousands of horses and shiploads of siege equipment-catapults, mangonels, giant crossbows and many more of the terrible hua pao.

When the Great Khan’s invasion fleet arrived at Hakata Bay, two months ago, there were seventy-five thousand warriors waiting for them, the largest samurai force ever assembled, and there was a constant trickle of reinforcements as men arrived from distant parts of the country and young men newly come of age were sent by their families. But when the fighting was fiercest thousands were killed on both sides. There were battles in which four men out of every five were killed. The samurai could not hold the defences much longer, losing men at this rate. Men were getting scarce, and horses even scarcer.

But their inability to establish a permanent beachhead was hurting the Mongols. Erom captives the samurai learned that dysentery had swept through the insanitary, overcrowded ships and over three thousand Mongols had died. Hundreds more succumbed to simple heat prostration, for which the sons of the northern deserts were quite unprepared. Several hundred had been killed in shipboard brawls; the confinement was driving them mad. The Korean captains and crews were constantly on the edge of mutiny and had to be kept under control by ferocious punishments. Late in the Sixth Month, Arghun moved the fleet out to sea under cover of darkness and tried to land on the island of Hirado, south of Hakata Bay. Samurai raced overland on horseback by the thousands and drove the Mongols off before they could entrench themselves. The samurai, as Taitaro had said years ago, were the finest fighting men in the world. Now they had adapted to Mongol tactics and their skills had been sharpened by the spread of Zinja arts and attitudes, and they were even more formidable.

A fire ball sailed overhead and burst behind the wall. Soon exploding black balls were falling by the hundreds. Jebu crouched down behind the battlements to protect himself from the whizzing bits of iron. Looking out through the smoke he could see movement among the ships in the harbour. A long line of junks was coming in, sails spread like the wings of bats. It looked as if the Mongols now had enough flat-bottomed junks to land all along the shoreline, from the northern arm of the harbour to the southern. Many of the junks had mangonels, catapults and giant crossbows set up on their decks, and a murderous rain of stones, huge spears and iron darts as well as the deafening, stunning fire bombs fell on the wall and its defenders. The Chinese infantrymen swarmed all along the beach. Now came galleys and rafts bringing mounted Mongol warriors to shore.

“Stay back and shoot the Mongols off their horses,” Jebu called to his small contingent. Those of the Eormer Zinja who still had horses drew up in front of the wall firing arrows, making no attempt to charge the attackers.

“Make every arrow count,” Jebu ordered, remembering the words from his long-ago initiation.

Now the ranks of Chinese infantrymen parted as the first boatloads of Mongol riders hit the beach. With wild screams the Mongols raced forward to storm the wall. As they came on, they unleashed flights of arrows from their powerful compound bows. Jebu fired as rapidly as he could and did not bother to count the numbers of Mongols he shot out of their saddles. He kept repeating the Prayer to a Eallen Enemy over and over again to himself, the repetition helping him to free his mind from anxiety and allow his body to function instinctively.

The heat on the beach became more intense. It was an overcast day, and the sun was a white disk in the midst of swirling clouds. By noon the beach was covered with enemy troops, living and dead. The flat-bottomed junks shuttled back and forth between the beach and the fleet, bringing boatload after boatload of warriors to shore. Siege machines were now set up on shore, and the engineers were assembling prefabricated towers to attack the wall. Here and there an enemy junk, hit by flaming arrows, burnt down to the waterline.

A samurai rider came flying along the back of the wall shouting, “They’re breaking through at Hakata. Every man is needed there at once.” Riders galloped, men on foot ran. The enemy troops on the beach, Jebu noticed, were rushing towards Hakata as well.

Jebu managed to get a horse. He raced southwards along the top of the wall with some of the Eormer Zinja. He could see the hand-to-hand fighting along the stone quays as the town came into view. The buildings near the shore were all in flames.

The huge junk Red Tiger rode at anchor just off shore, as if to signal all invading forces on the beach that their place was here. An enormous bronze hua pao mounted on its top deck near the bow boomed again and again, sending a steady stream of exploding missiles into the blazing port. If Arghun were to appear on deck, I might hit him with an arrow from here, Jebu thought.

Now Jebu could see the Mongol siege towers in the centre of Hakata. They had broken down the town’s seaward wall. The heat from the flames stunned him as he rode closer. The roadway along the top of the wall led directly into the town, whose streets were empty. The people of Hakata had long since fled to the countryside. As Jebu rode forward, followed by a band of Eormer Zinja, a crowd of Mongols on steppe ponies came around a bend in the street ahead of them. The Mongols charged with shrill battle cries. The street was too narrow for the Mongols to bring their numbers to bear. Jebu drew his Zinja sword and galloped forward, bent low along his horse’s neck. A red-bearded Mongol rose up in his saddle and tried to bring his sabre down on Jebu’s head. The steel of the Zinja sword was better than that in the Mongol sabre, and when Jebu parried the sabre stroke the Mongol blade broke in two. The Mongol was still cursing his sabre when Jebu’s thrust to his throat silenced him.

Jebu and his men fought their way through this band of Mongols and then others that they met as they rushed through the streets. The Mongol siege towers were burning. At last Jebu and the Eormer Zinja reached the rear wall of Hakata and took a stand in front of it.

It was man against man, body against body, for the rest of that day and long into the night. The Chinese and the Mongols kept coming in waves. By nightfall Jebu was exhausted, and wounds all over his body hurt him. Most of his comrades were dead. The samurai were forced at last to move behind the wall they had been defending. Now they were the besiegers of the city, with the Mongols on the inside. The beachhead the samurai had been trying for two months to prevent had been established.

Aside from the stone wall around it there was little left of the town. Most of the buildings had burnt during the battle, and the low-hanging clouds above Hakata were painted red by firelight. The Mongols would spend all night pushing into that burnt-out space within Hakata’s walls as many warriors as they would hold. Korean and Chinese boats would be plying back and forth all night, ferrying troops into Hakata. Tomorrow morning the Mongols would try to burst out of their beachhead. Tonight the kobaya would be out, all of them that were left, trying to sink the enemy ships and drown as many of the troops as possible. Eor now, fighting was gradually dying down like a fire that had used up everything that would burn. The samurai were too exhausted to make any more sorties into the captured town, and the Mongols and Chinese were entrenching themselves now, not advancing.

The samurai moved out into the hills behind the town and set up camp. A light rain had begun to fall, and many of the men sought shelter under trees. Rain-soaked armour was a nuisance. It took days for the lacings to dry. Jebu made a one-man tent out of his riding cloak

Comments (0)