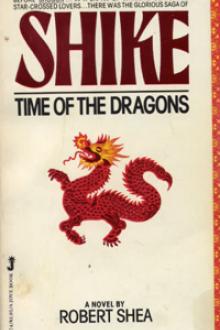

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

Kiyosi shook his head. “My father would accept no apology from Motofusa. And it’s not just he. Yukio, the youngest son of Muratomo no Domei, has reappeared. He is raising an army in Kyushu. Our spies say he wants to sail across the sea to fight for the Emperor of China. My father is sure Yukio wants to raise another Muratomo rebellion. So I must go to Kyushu and crush Yukio at once.”

Still shaken by the carriage brawl, still stunned by the realization that she had killed a man, Taniko felt a new fear clutch at her heart. “Must you go?”

“I am commanderin-chief of the army. I have advised my father to let Yukio go. All the malcontents in the Sacred Islands would flock to his banner, and we’d be rid of them once and for all. We wouldn’t have to lose a man. But my father will not be satisfied unless blood is shed. No victory is real to him unless men die for it.” The anger in his face faded and was replaced by a deep weariness.

“Oh, Taniko, I remember Yukio so well-that bright-eyed boy who used to play in the gardens of the Rokuhara. Every time I looked at him I felt a pang, knowing it was I who beheaded his father. I wondered if he knew it, and I wondered what he thought of me. He wasn’t much older than our Atsue is now, the first time I saw him. And now my father commands me to bring Yukio’s head back to Heian Kyo.”

Taniko held his hand while the carriage trundled along and he, in turn, patted Atsue’s head. “I’m so tired, Taniko. So tired of it all. How terrible it is that the fighting cannot stop.”

From the pillow book of Shima Taniko:

Last night my lord Kiyosi came to me and told me, with no great satisfaction, that the carriage of the Regent Motofusa was attacked by a troop of samurai as his procession was on its way to the Special Eestival at Iwashimizu. The samurai killed eight of Motofusa’s retainers, cut the oxen loose from his carriage and drove them off.

Motofusa’s carriage was too heavy for his remaining men to pull. He could have waited for more oxen or a palanquin to be brought, but he was afraid for his life, and so he walked home through the streets like any commoner and missed the ceremony. He has thus been publicly shamed.

Since Iwashimizu is one of Hachiman’s shrines, and Hachiman is the Muratomo patron, Sogamori thinks that in some obscure way he is hurting the Muratomo. By offending the god of war? This seems to me a dangerous way to get at one’s enemies.

Kiyosi brought a new flute for Atsue, a family heirloom called Little Branch, which has been his own favourite flute until now. At least, Kiyosi says, the Regent has paid many times over for the death of our bannerman and the fright he gave our little Atsue. Even the Regent, formerly the most feared official in the land, who once controlled the words and actions of the Emperor, can be chastised by the Takashi.

Each night before I fall asleep, even when I lie in Kiyosi’s arms, the face of the man I killed appears in my mind. His dead eyes seem to look at me and not to look at me. And in the darkness and silence of my bedchamber I feel a horror in the pit of my stomach. I have done a dreadful thing. Killed a man. There is blood on my hands and they will never be clean.

More than that, every night I see the look that was in the eyes of my little Atsue after he had seen me stab the bannerman to death. He knows now that his mother can kill. A nine-year-old boy should not have to live with such a memory. I see my own horror at what I have done reflected in his eyes. It is as Jebu told me. We are all part of one Self.

If that is so, the bannerman was I, and I was killing myself. Indeed, he asked me for death. The samurai often kill themselves or ask others to kill them, to avoid capture, mutilation and shame. What I did was not horrible. It was a mercy. Yet, the fact that I have killed another human being fills me with terror, because it is such a vast thing, such a final thing. Whether I have done it for right reasons or for wrong ones, it is taking for myself the powers of a kami. Such an act should be approached with fear, as one approaches a very holy place.

My Jebu-is he still mine after all these years?-has killed and killed again. By now he must have lost count of the numbers he has killed. I was there the first time Jebu killed a man. I remember how he stood looking down at the bodies of those he had killed for a long time after the fight was over. What was he thinking? I wish I could talk to him now.

I’ve asked Kiyosi how he feels about killing, but he doesn’t want to talk about it. He says the part of his mind that thinks about killing is sealed off when he is with me.

How lonely I will be when Kiyosi is gone campaigning in Kyushu.

-Third Month, twelfth day

YEAR OF THE HORSE

One night in the Eourth Month of the Year of the Horse, Yukio, Jebu and Moko sat together in the monks’ quarters of the Teak Blossom Temple and said farewell to the members of the Order who had been their hosts for so many months. In the morning their little fleet would embark for China.

Down in the town of Hakata over a thousand men were drinking, coupling, sleeping, writing or pacing about, waiting for dawn to come. At Yukio’s summons they had come from all the Sacred Islands, the last, dogged supporters of the Muratomo cause in a realm in which everyone bowed to the Takashi. There were wild men, half Ainu, from northern Honshu; there were hard-bitten warriors from the eastern provinces; there were Shinto and Buddhist military monks from the temples around Heian Kyo; there were near cannibals from southern Kyushu. All of them saw Yukio’s summons as a last chance to recoup the fortunes they had lost when the Takashi plundered the realm.

Eor the farewell to Jebu and Yukio, Abbot Weicho had ordered a hearty meal-the closest the Zinja ever had to a feast. There were raw fish, steamed vegetables, an abundance of rice, and a small jar of heated sake for each of the brothers and their guests. Though the women of the temple did not usually eat with the monks, Nyosan was also present.

They were halfway through the meal when one of the monks escorted a samurai to Yukio. He was one of the guards Yukio had posted some miles from the town.

“Perhaps this should be for your ears alone, Lord Yukio,” the samurai said. He was out of breath and clearly tired.

“If it is bad news, tell it to all of us. The more we know, the better prepared we will be.”

His calm manner seemed to reassure the samurai, who nodded and said, “It seems the Takashi have learned of your plans, and they mean to prevent you from going. An army of ten thousand men crossed over from Honshu two days ago. They are now less than a day’s march from here. They’ll be here tomorrow for certain.”

“Then they’ll arrive too late,” said Jebu. “All they’ll see will be our ships sailing out of the harbour.”

“They may revenge themselves on the townspeople and the monks for helping us,” said Yukio.

“Don’t worry about that,” said Weicho. “We’ll protect our own. If need be, we’ll teach them that the Order is still to be respected, even if we have lost a few members.”

Yukio stood up. “There are still things to be done. I thought something like this might happen, and I have given some thought to pre paring for it. I apologize for leaving this feast, Holiness, but there are arrangements I must make in town.” With a smile and a bow, the slight figure turned and strode to the door, where he buckled on his dagger and sword and went out.

Before sunrise the next morning the quays of Hakata were alive with the thump of bales and boxes, the clank of weapons and the shouts of young male voices as Yukio’s men assembled. In a few hours, according to word from scouts Yukio had sent out, the Takashi army would be upon them.

The warehouse workers sweated in the cool dawn air as they raced to load each ship with provisions for a voyage of ten days. The ten ships were oceangoing galleys designed to carry both passengers and freight. Eight had sails stiffened with bamboo battens to catch any favourable wind that might help the oarsmen. At stem, stern and masthead the ships were bedecked with white Muratomo banners and pennants and streamers bearing the crests of other samurai families joining in the expedition.

As the sky above the hills around Hakata turned a paler blue, the samurai began to board the ships. Some of them bade goodbye to sombre little family groups that had accompanied them this far on their journey. Others, reeling drunk, were half carried to the docks by the women with whom they’d spent their last night on shore.

Long before dawn Nyosan and Jebu made the long downhill walk from the Teak Blossom Temple. Now, dressed in the ankle-length grey robe and black cloak of a woman elder of the Order, Nyosan gazed up at Jebu with shining eyes. Jebu had to bend almost double to put his arms around her and kiss her.

“That such a great, huge man should have come out of a tiny creature like myself,” she laughed.

“I will miss you, Mother.”

She shook a finger at him. “We have said goodbye too many times in too many ways to feel sadness now. Perhaps you will find your way to the land of your father. I hope, if you do, that it sets your heart at rest.”

Jebu looked out past Shiga Island, a sandspit at the tip of the northern arm of the bay, as if trying to see the fabled land that lay to the west. As he looked, a long, dark shape slid past the island. It was followed by another.

A silence fell over the quays. Then a murmur rose as ship after ship appeared in the entrance of the bay. The murmur grew as, oars sweeping rhythmically through the waves, the vessels sailed closer. The bright banners that bedecked the ships became visible. The banners were blood-red.

“We’re trapped,” said a man near Jebu.

“Might have known the Takashi wouldn’t let us leave,” said another.

The crowd parted and Yukio strode down to the edge of the water. Eor the occasion he wore his finest suit of armour, silver-chased with white laces. A silver dragon roared defiance from his helmet. The men watched him closely.

He smiled when he saw the Takashi ships. “They honour our departure with an escort.” Some of the men laughed hesitantly.

Yukio stepped to the edge of the pier and raised his arms. Silence fell over the assembled samurai.

“0 Hachiman-Yawata, my great-grandfather was known as Hachiman Taro, your firstborn son. Now, in my family’s hour of greatest need, I call upon you to give us your aid. Bless our journey across the great water. May we find the good fortune we seek in China. May we return one day, victorious,

Comments (0)