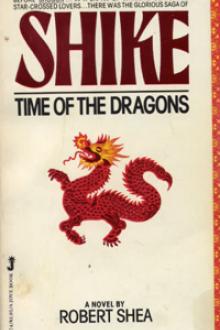

Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕

- Author: Robert J. Shea

- Performer: -

Book online «Shike by Robert J. Shea (the reading list txt) 📕». Author Robert J. Shea

KUBLAI

Because men suffer, they fight and kill one another. The innocent, who begin by fighting to defend themselves against robbers and murderers, become robbers and murderers themselves. Someone must protect them, both from what happens to them and from what they become. It is our hope that we can take upon ourselves the duty of necessary fighting and killing. We think we can be trusted.

THE ZINJA MANUAL

Summer came to Heian Kyo. The screens and lattices of houses were opened to the air as the days grew longer and the nights warmer. Rain and sun alternated to deepen the green of the huge old willows that grew along the avenues and canals. Moon and fireflies lit the night. Taniko found that she missed Kiyosi terribly. She wanted to share this beauty with him. Unable to talk to him, she wrote poems, two or three a day, and imagined herself reading them to him.

The sun warms the wind,

The wind strokes the willows,

The willows reach down to caress the river.

She had little to record in her pillow book. She liked to write about the gossip of palace and Court, the problems of the country’s rulers, the struggles of powerful men. About all this, she had heard in abundance from Kiyosi. Since he had sailed south to Kyushu her life had been one of isolation, monotony and boredom. It was no consolation to her that it was the same for almost all women of her station, except the few lucky enough to have duties at Court. She had no idea how other women managed to tolerate such lives.

Her one source of daily joy was the companionship of Atsue. The boy had quite forgotten his horror at seeing his mother stab a man to death, and the two spent hours together every day. Atsue was growing to look more and more like his grave, square-jawed father. Every fifth day she took him by carriage to the Buddhist temple on Mount Hiei for lessons on the flute and koto with a famous master. Daily she listened to his practice on these instruments. She finally convinced him the samisen was worth learning and gave him lessons herself. Kiyosi had taught him go, saying that every samurai should play the game well, and Taniko played it with Atsue night after night. She took him for walks through the garden, teaching him the names of summer herbs and flowers. Late in the evening, just before he went to bed, they would sit and watch the moon rise. Atsue would play on his flute just for pleasure, and his playing was often so beautiful it brought tears to her eyes.

A strange silence fell over the Shima household in the middle of the Eifth Month. Taniko’s maids seemed nervous and chattered less than usual while helping her dress and undress. There was something furtive in the way her aunt and cousins greeted her in the women’s quarters and hurried past on business of their own. Ryuichi’s oldest son, Munetoki, now a fierce young samurai of nineteen, had gone off with Kiyosi’s expedition to hunt down the last of the Muratomo. Uncle Ryuichi seemed to have disappeared completely. When she asked about him, Aunt Chogao said he had gone on a long journey by sea to Yasugi on the west coast. Yasugi, Taniko knew, was a stronghold for the pirates who preyed on the Korean coast and shipping. All her life she had been hearing rumours that her family was involved with pirates; this seemed to confirm it.

One afternoon a servant announced that the first secretary to Lord Takashi no Sogamori was in the main hall and had asked to visit her. She felt a little leap of pleasure. She had not had a letter from Kiyosi in nearly a month. She hurriedly prepared herself with her maid’s help, set out the screen of state in her chamber and sent her maid for Sogamori’s secretary.

She immediately noticed the willow-wood taboo tag tied to the secretary’s black headdress and dangling down the side of his face. She wondered if the evil that beset him was a personal misfortune or something that had fallen upon the entire house of Takashi. It would not be polite to enquire. It was surprising that a man under taboo would even leave his house. He must consider the visit essential.

She had never seen the man before, but she recognized the type. His prim manner and old-fashioned, slightly tattered robe and trousers proclaimed him a Confucian scholar. Doubtless a man of good family whose declining fortunes had forced him to go into service with a rising clan like the Takashi.

They exchanged greetings, the secretary peering nervously at the screen as if trying to see through it. He wants a look at the famous lady who delights Kiyosi, she thought.

At last the secretary said, “Lord Sogamori has sent me to you to inform you of his wishes.”

“I am honoured,” said Taniko. “But I had hoped you might have a message for me from Lord Kiyosi.” Through the openings near the top of the screen she could see that the man’s eyes had widened in surprise-and possibly fear-at the mention of Kiyosi’s name.

“There was no message,” he said hastily. “Lord Kiyosi sent no mes sage.” There was something in his voice that frightened Taniko. “What is it then?” she said. “What are you doing here?” “Lord Sogamori desires that his grandson be sent to him.”

The secretary’s words surprised Taniko and intensified the dread she felt. “Eor how long?”

Again the secretary seemed surprised. “Why, for the rest of his life, my lady. Lord Sogamori wants to give the boy the Takashi name and adopt him as his own son.”

“His son? But he is Lord Kiyosi’s son. He, if anybody, should adopt him.”

“My lady,” the secretary said, then stopped. He seemed at a loss for words. At last he blurted out, “A dead man cannot adopt a child.”

It was as if he had plunged a sword into her body. She sat paralysed, impaled on his words. At last, as the numbness of shock faded away, she began to feel pain and struggled to free herself.

“No, no, he is not dead. Someone would have told me. You can’t come here and say that he is dead. I would have known about it if something had happened. You’re wrong. You must be mistaken.”

Even as she denied his words, it struck her with overwhelming force: Kiyosi had been killed in the fighting in Kyushu, and no one had told her.

The secretary blushed a deep scarlet. “Don’t you know what happened, my lady?”

“I have heard nothing. Surely I would have heard if anything had happened to Lord Kiyosi.”

Again the man seemed to grope for words. “Then I-I must tell you? How unfortunate. But seemingly it falls to me to do this duty where others have failed.” He drew himself up and composed himself into a picture of Confucian rectitude. “My lady, it grieves me greatly to be the bearer of this news. Six days ago, we received word that there had been a great sea battle at Hakata Bay. The rebellious Muratomo forces were trying to escape. My lord Kiyosi was on the flagship of the Takashi fleet. During the fighting he was struck in the chest by an armour-piercing arrow. Those who were near say he died instantly. One arrow, no pain. His body fell into the sea and disappeared immediately. He is gone, my lady. He died faithfully carrying out his father’s orders. You may take pride in that.”

Taniko heard the man out. Then she stood up.

The next thing she knew, she was lying on the floor, her maid kneeling beside her, wiping her face with a damp cloth. She struggled to sit up. The screen was knocked over, and the Takashi family secretary was standing in a corner of the room with his face politely averted.

Then it came back to her. Kiyosi was dead.

She looked up at the maid, one of the women who had come with her to Heian Kyo years ago. The maid was crying.

“You knew,” said Taniko. “You knew days ago and you didn’t tell me.”

“I could not, my lady,” the maid sobbed. “I could not bear to be the one. Why should it have to be me?”

In spite of the shock of grief, Taniko’s mind was still working. “Set up the screen.” The first thing she must do was get rid of this man with his talk of taking Atsue. When the screen was raised, Taniko composed herself and sat behind it.

“Please tell Lord Sogamori that I am overwhelmed with gratitude at his offer to adopt the boy Atsue. However, with the greatest respect, the Takashi family has no obligation to do anything for either Atsue or me. Atsue is my son, and it is my desire that he stay with me.”

The secretary stared. “My lady, the boy is Lord Kiyosi’s son. Lord Sogamori has lost his own son, his eldest-the son he loved best in the world. He wants his grandson. You cannot deny him.”

It was agony to sit upright, agony to hold her voice to a soft, polite tone, agony to speak at all. She clenched her hands in her lap, digging the fingernails of one into the back of the other. “I am very sorry, but Lord Sogamori has other children and grandchildren. I have only Atsue. I am sure he would not want to take my only child from me.”

“Excuse me, Lady Taniko, but this is most unwise. You only bring more suffering upon yourself. Lord Sogamori is the most powerful man in the Sacred Islands.”

“My son does not belong to Lord Sogamori. I do not belong to Lord Sogamori. I have nothing more to say.”

His mouth drawn down, the secretary left her. Taniko sat without moving for as long as she could, while her grief welled up inside her until she felt it would tear her apart. She began to gasp like a deer with an arrow in its chest. Her gasps became sobs. At last she screamed. She threw herself full length on the floor, tearing at her robes and beating upon the polished floor with her fists.

Her maids rushed in and tried to hold her. She struck them away. Drawing her body into a knot, she shrieked and wept.

Atsue came in. Horrified at the sight of his mother, he turned to the maids, who stood whimpering and wringing their hands.

“What’s happened to my mother?”

Still sobbing, Taniko pulled herself to a sitting position. Thank Amida Buddha I can be the first to tell him, she thought. At least he won’t get the news from some servant. She reached out and pulled the boy to her, fighting for breath, trying to get her voice under control.

“Your father has-left us. He has gone to the Pure Land. He died in battle at sea off Kyushu. I have just heard it.”

“Oh no, Mother, no, no, no.” The boy’s arms tightened around her neck until she thought he would break it. But she endured the small pain gladly. She had only Atsue to live for.

Eor hours they cried together in each other’s arms.

In the evening the maids brought food to them. Taniko could not eat. She watched Atsue pick at the small slivers of fish with his chopsticks. In his green silk tunic and black trousers he looked like a replica of Kiyosi.

Why didn’t they chop me to bits with swords and be done with it? Taniko thought. How long could she feel this pain before she went mad?

“Homage to Amida Buddha.” Taniko started to recite the invocation. Atsue put down his chopsticks and joined her.

After the maid took away their dishes,

Comments (0)